As the Taliban have moved closer to Kunduz city, more civilians are being injured. Abdulrahman, 14, lost his left hand earlier this month while gathering wheat when a mortar from a nearby Afghan army base landed beside him. Photographed July 14, 2021. (Lorenzo Tugnoli/For The Washington Post)

KUNDUZ, Afghanistan — The argument between Afghan security forces erupted two miles inside Taliban-controlled territory, piercing the near-complete silence and threatening to unravel a night of modest gains in a city under siege.

Around 3 a.m., a small team of elite special forces were halfway through an operation to retake a sliver of territory along the city’s northern edge when a police unit that was ordered to establish checkpoints along the way refused to advance.

“Who are you from Kabul to give us orders?” a police commander said to a special forces officer. “This is your territory, your city, if you don’t protect it who will?” the officer replied. A compromise was eventually brokered: The operation would go no further, but the police unit would establish an outpost at the stopping point to hold the gains.

Hours later, the police fled, abandoning their checkpoint and ceding the territory back to the Taliban.

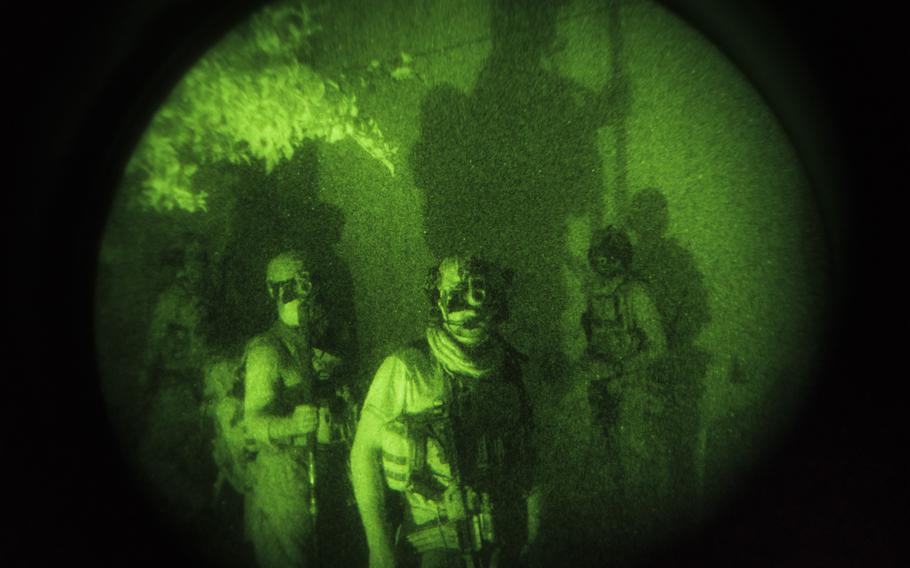

An elite special forces unit conducts a clearing operation in an area under Taliban control in Kunduz, Afghanistan, in July 2021. (Lorenzo Tugnoli/For The Washington Post)

For weeks, the Afghan military has struggled to hold provincial capitals such as Kunduz after losing huge swaths of the country’s rural territory in a surge of Taliban attacks that came as U.S. forces withdrew and U.S. air support dropped. The Afghan air force can only provide a fraction of the coverage American warplanes once gave, so Afghan ground forces are used to fill the void.

But the capabilities of those ground forces are uneven, resulting in government advances that often rapidly evaporate. Experienced and motivated elite units are leading the battle to retake territory, but the troops called up to secure those gains - the army, police and irregular fighters - have intermediate to no training and inconsistent support, and they are generally less inclined to fight.

The elite special forces unit, known as the KKA or Afghan Special Unit, that leads many of the clearing operations in Kunduz includes some of the country’s most capable and motivated soldiers. The United States and NATO trained the unit to conduct important, dangerous missions: night raids against specific targets such as suspected Taliban commanders, weapons depots or supply chains.

These are the fighters that most closely reflect President Joe Biden’s characterization of the country’s military, equipped with “all the tools, training and equipment of any modern military.” Yet Afghanistan’s special forces represent less than a fifth of the country’s security forces.

Before the dispute put a stop to their advance, the Afghan special forces’ operation earlier this month moved quickly and with precision.

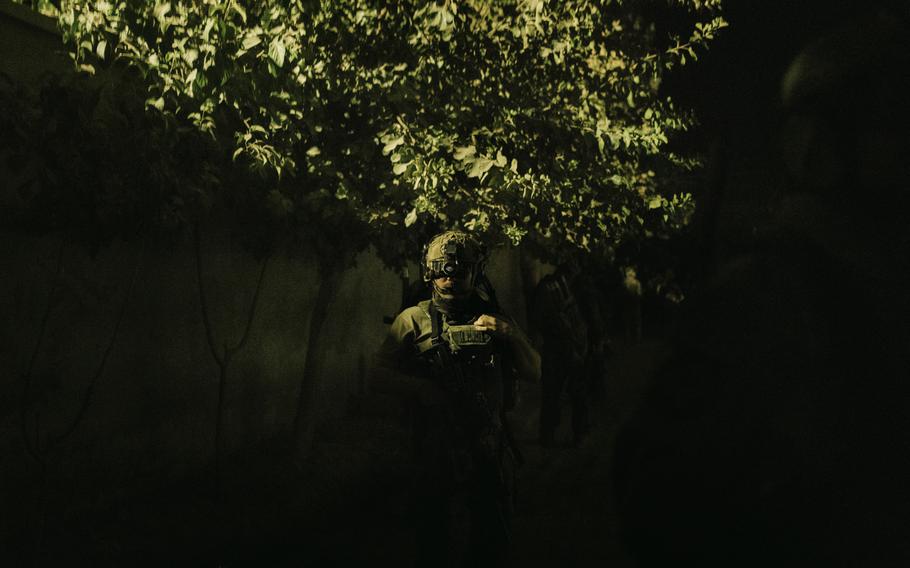

The special forces unit called off the operation after the friendly fire incident, blaming the other security branches for the lack of coordination. Photographed in Kunduz, Afghanistan, on July 15, 2021. (Lorenzo Tugnoli/For The Washington Post)

First Lt. Abdullah Ansari, 30, led the team retaking territory house by house. His small unit set out on foot, slipping through the darkness in silence, motioning commands only visible through the night-vision goggles attached to their helmets. As they moved, they scanned alleyways and gardens covered in grape trellises, and climbed through abandoned buildings.

“What’s happening, what’s up there?” Ansari called out. In one of the houses, the soldiers found a family, some of the few civilians who remained in the area. “Please don’t, please don’t,” a woman pleaded.

“You, young boy, come over here!” Ansari called. One of the other soldiers said the young man was old enough to be a member of the Taliban. “He’s so young,” the mother said, begging. “My heart would ache, I’m a mother, don’t you have a mother?” Ansari called intelligence officers to the house to interrogate the family before moving on.

As the operation progressed, Ansari marked each block as cleared on a satellite mapping app on his phone, the screen brightness as low as possible to protect against Taliban snipers.

When he found out the next morning that the police had fled their checkpoint, he said he “felt like everything was for nothing.”

At checkpoints marking Kunduz’s front line, police units rejected accusations that they often run from Taliban attacks. But the city’s police chief was more blunt.

“We are being asked to perform a job that we were not trained to do,” Zabardast Safi said. “My men have been pulled into fighting a war. This is not their responsibility. That is for the Afghan army.”

Ansari said the debacle on Kunduz’s northern edge made him miss working with U.S. troops, when his missions felt meaningful. “Now everything is just messy,” he said.

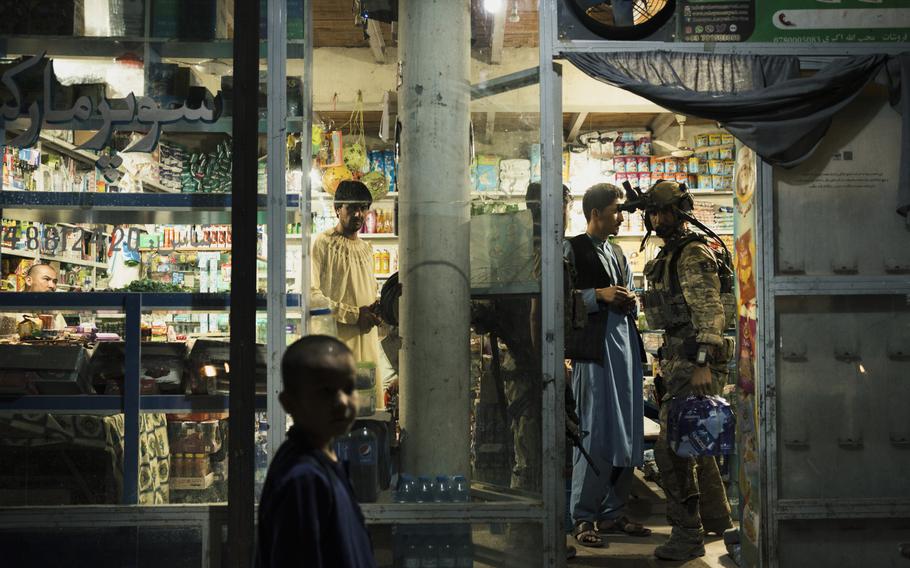

KKA forces stop for water in a local shop just a couple of miles from the front lines before a night mission in Kunduz, Afghanistan, on July 12, 2021. (Lorenzo Tugnoli/F or The Washington Post)

For residents of Kunduz and other contested provinces, “messy” Afghan military operations have meant a drawn-out conflict that has caused civilian casualties to spike, according to the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission, and forced tens of thousands of Afghans to flee their homes.

“The fighting was quick before,” said Ghusuldin Muhammadi, 62, who fled into the city from his home on the outskirts when the Taliban overran Kunduz city in 2016 and again in 2018. Both times, a heavy barrage of U.S. airstrikes helped Afghan forces push back the militants in a matter of days. This time, the battle has stretched into its fourth week.

“We don’t know when our neighborhood will become secure,” Muhammadi said. For the past three weeks, he and his family have been living in a shelter made of tree branches and worn cloth.

“For both sides, we are just like wood to keep the fire burning,” he said when asked whom he holds responsible for the massive displacement in his province and elsewhere in the country.

This new phase of the Afghan conflict, which comes as U.S. officials say the withdrawal is 95 percent complete, has also seen an increase in the use of artillery in urban areas, according to civilians and security officials in Kunduz.

Many of the families displaced in the recent fighting have been forced to live in in a school and in makeshift shelters on the campus in the provincial Afghan capital Kunduz. Photographed in July 2021. (Lorenzo Tugnoli/For The Washington Post)

The central hospital in Kunduz has been flooded by victims of the violence, at times overwhelming the staffing and equipment. Abdulrahman, a 14-year-old who goes by a single name, lost his left hand at the wrist when a mortar he claimed was from a nearby Afghan army base landed beside him earlier this month. Weeks later he was still confined to a hospital bed, being treated for shrapnel wounds to his head and stomach.

“I didn’t hear any sound or explosion, I just remember opening my eyes and seeing dust and smoke,” Abdulrahman said. He said he was gathering wheat when the blasts hit. “I realized my head was hurt and my hand was gone. That’s when the second mortar hit.”

Abdulrahman has grown up in Kunduz and is accustomed to the sound of gunfire and other clashes, but he said mortar fire never landed so close to his home. Unable to eat for days, Abdulrahman grew faint as he spoke.

“The Taliban say they are trying to capture the city, but for what?” he said. Tears streamed down his face as he shifted from anger to sadness. “All of this is just killing people.”

The province’s central health department has recorded nearly 700 injured civilians since Taliban fighters began their push on Kunduz. The majority suffered from gunshot and shrapnel wounds, according to health department records.

Elite Afghan forces conduct a clearing operation in an area under Taliban control on the northern edge of Kunduz, Afghanistan, on July 15, 2021. (Lorenzo Tugnoli/For The Washington Post)

A few days after the night mission, government forces prepared for a second operation on the city’s edge. The goal was the same - strengthen the provincial capital’s security perimeter - but the scope larger. Multiple police, army, intelligence and local militia units would take part, dividing into two teams operating at the same time in different neighborhoods.

A day of planning secured air support and lines of communication and allowed the different security force branches to swap coordinates. At a final meeting, half a dozen commanders met in the garden of small police outpost to compare satellite maps on smartphones over cigarettes, tea and energy drinks.

Ansari radioed to his commanding officer. Everyone was sweating from the sudden sprint and adrenaline rush.

“It was friendly fire,” Ansari said, muttering a string of expletives. Ansari said Afghan army soldiers at a nearby base mistook them for Taliban and opened fire.

“This is a cancer! There is no coordination!” Ansari said, exasperated. The one injury was minor: A soldier’s left arm had been grazed by a bullet. After holding in place as another argument erupted over the radio, the entire operation was called off.

A local spokesman for the Afghan army in Kunduz, Abdul Hadi Nazari, said he was unaware of the incident.

“There is no discipline, no support, so it feels like nobody cares about us,” Ansari said. “It’s like everything is just for nothing.”

The Washington Post’s Aziz Tassal contributed to this report