The USO Pat Tillman center at Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan, is empty July 7, 2021 after a transfer of the base from the U.S. to Afghan forces the previous week. (J.P. Lawrence/Stars and Stripes)

BAGRAM AIRFIELD, Afghanistan — The murals that once celebrated U.S. military units have been painted over and the settings that memorialized the fallen are now empty spaces.

Most of Bagram Airfield, the largest U.S. base in Afghanistan for much of the past 20 years, is a ghost town.

But in the days before coalition troops left on July 2, some of the last to leave scrambled to safeguard war mementos or make sure that what stayed behind wouldn’t be left to whatever comes next in a country still at war.

Many of the cavernous, empty structures the U.S. vacated were left open, but one in particular remained locked during a recent visit: a squat wooden lodge near the base’s airport terminal, once known as the USO Pat Tillman center.

It’s where Rebecca Medeiros, former USO country director in Afghanistan, spent the last year cataloguing mementos.

“It’s important those things came back to the U.S., instead of being left behind in Bagram, where we don’t know the future of that location,” Medeiros said. “We don’t know if those items would be taken care of, or their meaning would be understood.”

Atlanta Falcon Warrick Dunn, left, and New England Patriot Larry Izzo toss out autographed footballs to the troops before the ribbon-cutting ceremony to open the Pat Tillman USO Center on Bagram Airfield, in April 2005. The center is dedicated to the former NFL player killed in action while serving in Afghanistan in 2004. (Michael Abrams/Stars and Stripes)

The USO center, named after the former NFL player and Army Ranger who died in Afghanistan, hosted some 2 million troops, contractors and civilians waiting for flights over 16 years, allowing them to watch movies, play video games and connect to Wi-Fi.

The USO kept employees at Bagram as long as possible, in part to ensure that the mementos soldiers left there could be brought home, said Alan Reyes, the organization’s chief operating officer.

“We do our best to preserve artifacts of historical or symbolic significance to us,” Reyes said.

The centerpiece was a framed Tillman jersey, “which means a lot to people,” Medeiros said.

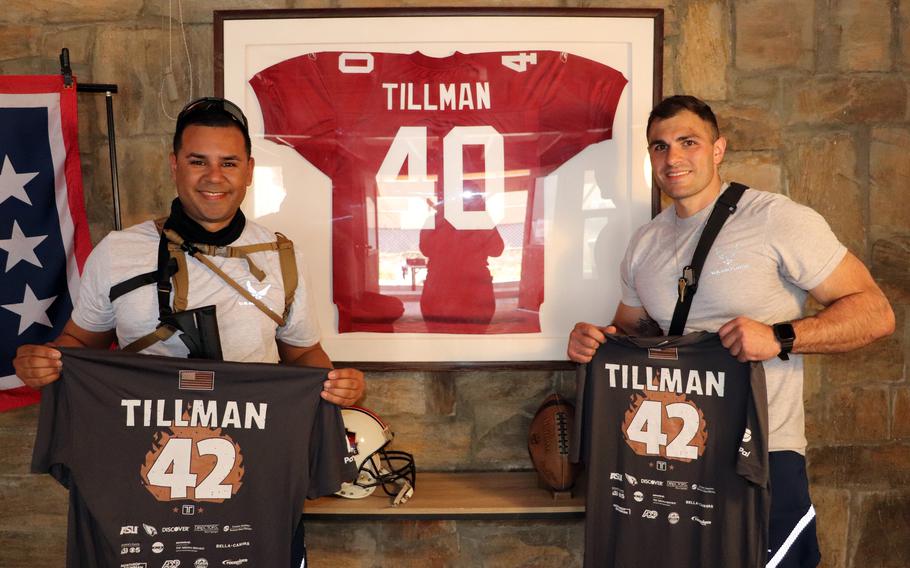

Airmen pose with the jersey of Pat Tillman, a former NFL player who joined the Army Rangers, after a memorial run April 23, 2021 at Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan. (Kimberley Culverhouse-Steadman)

Elsewhere around the sprawling base, troops saved a memorial to five soldiers and contractors killed in a 2016 suicide bombing. It’s in transit to Fort Hood, Texas, where it will be re-dedicated, said Michael Garrett, spokesman for the 1st Cavalry Division Sustainment Brigade.

A plaque for troops from the Czech Republic has been taken to Prague, where it will become part of the Military History Institute’s collection, said spokeswoman Lt. Col. Vlastimila Cyprisová.

A steel beam from the World Trade Center, donated to Bagram as a memorial, became a concern after no one could initially remember where it went. They eventually learned it had been relocated in 2015 to Fort Drum, N.Y.

Much of the work done by several people during the final stretch was “sanitizing” Bagram.

“We pulled off stickers, signs went down,” said Kimberly Culverhouse-Steadman, who came to Bagram in February to close the USO and bring back its mementos. “They just didn’t want anything reminiscent of American presence.”

This effort was to “ensure consistency in appearance,” said Col. Jennifer Spahn, spokeswoman for U.S. Forces — Afghanistan, in a statement Friday.

Murals on blast walls at Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan, were blank July 7, 2021, after being painted over prior to U.S. troops transferring the base to Afghan security forces. (J.P. Lawrence/Stars and Stripes)

Some objected to painting over the murals at Bagram, including James Von Holland, a contractor at Bagram who has photographed hundreds of murals during his time at U.S. bases in the Middle East.

“I didn’t like it at all,” Von Holland said. “It’s like going into the Louvre and destroying the Mona Lisa.”

Von Holland and some contractors at the base said they were frustrated due to the pace of the drawdown and what seemed like endless, sometimes contradictory orders. Several contractors and civilians said they went on vacation and were surprised to find they weren’t allowed to return.

All U.S. troops, contractors and civilians were supposed to leave Afghanistan by May 1, the deadline that the Trump administration agreed to with the Taliban last year. But the Biden administration moved that deadline back to Sept. 11.

As May 1 neared, those on Bagram were “on edge,” fearing the Taliban would retaliate against U.S. troops staying past the original deadline, Culverhouse-Steadman said.

She recalled the days when Bagram was bustling with thousands of troops, contractors and civilians.

Upon arriving in late February this year, she was struck by the emptiness. The base’s large main post exchange had been reduced to one row of goods, she said.

The main post exchange at Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan, which once bustled with shoppers, stands empty July 7, 2021, after U.S. troops left the base. (J.P. Lawrence/Stars and Stripes)

At one point during the drawdown, a building housing U.S. Special Forces in Kandahar burned down, leaving 25 troops without shelter. The USO sent bedding, pillows and blankets, she said.

Cafeterias at Bagram began closing in mid-June, leaving many of the last Americans there stuck with Meals, Ready to Eat.

Cookies, beef jerky and 700 pounds of instant ramen noodles were sent to the remaining troops who secured the base, the medical staff, Air Force investigators, and the personnel who handled the shipping yard and customs.

Culverhouse-Steadman flew out May 25 with two black suitcases — one with her personal effects, and the other with the Tillman jersey and other keepsakes.

Right before boarding the packed government-chartered flight, she was told she’d have to choose between the bags in order to board.

She chose to leave her personal effects behind. Fortunately, a friend from the post office agreed to mail her that suitcase.

The Tillman jersey is now at USO headquarters in Arlington, Va. It may be sent later to Arizona, where his family and foundation are based, the USO said.

Zubair Babakarkhail contributed to this report.