Middle East

Stranded Afghan interpreters hold last hope for US visas

The Washington Post July 3, 2021

Abdul Rashid Shirzad with his family in Kabul, Afghanistan, on July 1, 2021. (Paula Bronstein for The Washington Post)

KABUL, Afghanistan - The letters from his American military superiors glowed with superlatives. Abdul Rashid Shirzad, they wrote, was a "true hero" and a man of "great character and integrity" who had acted courageously under fire to save American lives during more than two years as a battlefield interpreter.

In short, the formal commendations from three Navy SEAL commanders said, Shirzad was an exemplary model of how such interpreters - hired to help U.S. forces understand Afghan society and communicate in dangerous conditions with Afghan officials, villagers and prisoners - should perform their job.

But in 2016, three years after his stint with U.S. Special Operations forces ended, Shirzad's application for a Special Immigrant Visa to the United States was denied. The terse letter from the U.S. Embassy in Kabul said that he had failed to provide "faithful and valuable service" and that his case "lacked sufficient documentation." No explanation was provided. Stunned, he said he appealed but never heard back.

Today, Shirzad, 35, is one of thousands of former Afghan interpreters for U.S. military and civilian agencies whose visa cases have been languishing in bureaucratic limbo. Now with U.S. forces leaving the country, their hopes have suddenly been raised by a promised mass evacuation plan, still in the initial stages, that could send them to third countries to complete the process - though with no guarantee of approval.

In interviews, a half-dozen former interpreters with pending cases, including Shirzad, said they had not been notified about the evacuation plan. The U.S. Embassy in Kabul said it could not discuss individual cases.

"I gave everything I had to the Americans, but once they are gone, I will be killed," Shirzad said. He said Taliban extremists have hunted down and killed some former interpreters and sent threats to many others, including him. "They keep track of us, and they don't shoot us like they do Afghan soldiers. If they catch me, they will behead me."

In recent weeks, several NATO allies who fought alongside U.S. troops in Afghanistan, including Germany, France and Australia, have evacuated hundreds of Afghan interpreters as their own forces have withdrawn. Britain announced a new policy in April that would make it easier for interpreters to apply for asylum.

The Biden administration, under pressure from Congress and other critics, announced it would create its own evacuation plan, potentially affecting thousands of special visa applicants. Last week, Biden said that "Afghans who helped us are not going to be left behind." But the plan has not been finalized, and in-person interviews have been halted at the U.S. Embassy because of a recent coronavirus outbreak that left one staff dead and sickened more than 100 others.

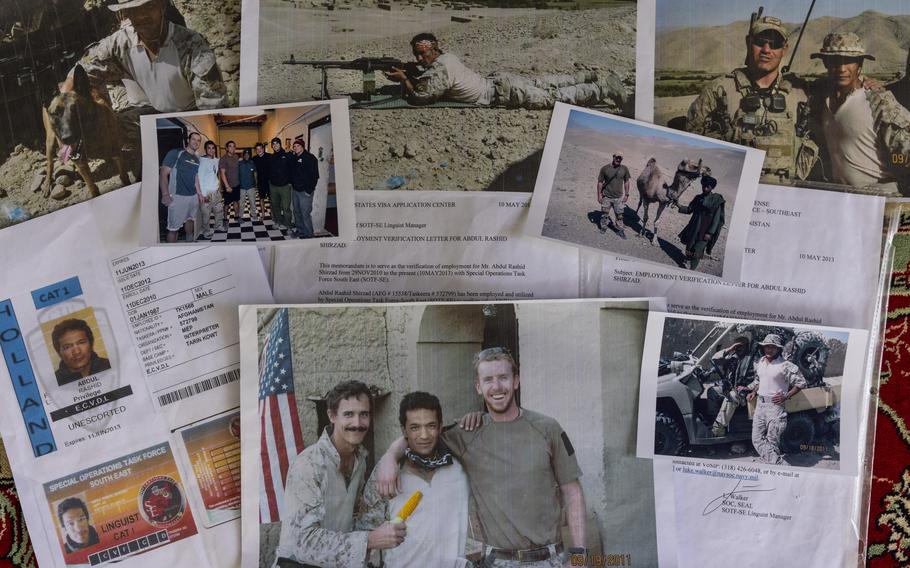

Photos and letters from the military collected by Abdul Rashid Shirzad. (Paula Bronstein for The Washington Post )

An embassy spokesperson, Hilary Fuller Renner, said it had received no specific information about how the evacuation plan would work or when it would begin. State Department officials have said in-person visa interviews will resume as soon as it is safe, while other reviews will continue in Washington.

Statistics released by the State Department show that of more than 26,000 special visa slots, including several thousand that were added after 2014, 15,500 visas were issued by the end of 2020 and another 11,000 remain available. Officials said approximately 18,000 former interpreters and other Afghans are at some stage of the application process, and roughly half would probably be found eligible. The cap on visas does not include family members.

Several former interpreters expressed concern that if they were sent to another country for processing but were denied, they could be sent home to an uncertain fate. One applicant, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of being targeted by the Taliban, said that if he were offered the chance to leave but not guaranteed a visa, it would be a difficult choice.

U.S. officials were initially said to be considering the island of Guam, a U.S. territory in the Pacific, for offshore visa processing.

"Immigrating to another country is a big decision, for my family as well as myself," the applicant said. "Even waiting uncertainly for six months in a foreign country is hard. My life has been up in the air for years already. Should I disrupt everything when I don't know what the result will be?"

But Shirzad, one of a group of interpreters who held a protest in Kabul last month demanding faster U.S. action on their visas, said news of the evacuation plan had revived his long-abandoned hopes for reaching a safe haven.

"I don't care where they send me. I just want to be safe with my family," the father of three young boys said this week in an interview at his home. Even eight years after he left U.S. service, he said he remains fearful.

Since May, Taliban forces have captured scores of districts across Afghanistan in an aggressive offensive. Afghan forces have pushed them back in some areas, with help from local volunteer fighters, but recently the extremists have surrounded several provincial capitals and seized districts in four areas close to the Afghan capital, according to Afghan officials and media reports.

Peace talks between Taliban and Afghan leaders have made no progress since September, while the extremist group claims it has defeated U.S. forces and expects to lead a pure Islamic State. Its leaders have said they will treat Afghan civilians mercifully but punish those who have worked for the Afghan or U.S. governments.

In recent interviews, several former interpreters expressed frustration with what they described as an arbitrary, confusing and opaque visa application system. Some said they were rejected and appealed but received no response. Others said the process took so long that supporting material for their cases, including costly medical tests and affidavits from long-ago supervisors, had to be resubmitted.

In the meantime, most of those interviewed said they had been unable to return to their home villages or areas, because their ties to U.S. forces are widely known. Instead, they are living in cities, often jobless or underemployed. Shirzad, who speaks fluent English, now runs a local shop and says he gets little chance to use his language skills.

Abdul Rashid Shirzad poses at his home in Kabul, Afghanistan. (Paula Bronstein for The Washington Post)

"The Taliban have taken control of my village. I can't dare to go home to our farm. I can't even go on a picnic. I have become a prisoner of my house," said Omid Mahmoodi, 31, who worked with U.S. forces for three years in Kabul. He said one of his former fellow interpreters, who worked for French forces, had been "tracked down and killed by the Taliban."

Mahmoodi said he applied for a special U.S. visa last year, after passing regular background checks during his years with the U.S. military, but was rejected on the grounds that he had failed a polygraph test. He said others had been rejected because they had not quite completed the two-year minimum U.S. employment to qualify for the visa, or had their work contracts unexpectedly "terminated."

"Many have been terminated for no given reason," Mahmoodi said. "For the Taliban, it doesn't matter if an interpreter has worked for one day or one year, or if he has been blacklisted or terminated. In their eyes, he has been marked as an infidel supporter and ally of the invaders."

Individual complaints of unfair visa denials are difficult to verify, but U.S. officials have said that in many cases, applicants are rejected due to suspicion or evidence of fraud, such as submitting fake identity documents or falsifying work histories.

Many Afghans who apply for special visas may qualify on some grounds but not others. Some, such as drivers for civilian aid projects, can prove where they worked and submit bona fide letters from their American superiors but cannot prove they were exposed to danger - except in vague terms that would apply to large numbers of other Afghans.

Military interpreters usually have much stronger cases and higher acceptance rates. But sometimes, other factors may carry more weight than harrowing descriptions of battlefield conditions. U.S. officials have said even interpreters with strong recommendations from their military superiors may commit offenses such as theft or assault that get them fired.

Abdul Zubair Ebrahemi, 30, worked for the U.S. Army for three years and spent another three waiting for his visa, which was denied. As a combat translator, he said, "I was always on patrols. I served in the most dangerous southern provinces. I have medals and commendation letters. I was serving my country by helping America. I expected the U.S. government to support me."

Instead, Ebrahimi said, his visa was denied because he had been "terminated" by the U.S. contracting firm that hired him. When he asked why, he was told the company was "not authorized to share the details." When he heard about the planned U.S. evacuation plan, he said, "it gave me a huge hope, but because of this termination on my record, I am worried that I might be left behind."

For Shirzad, the startling disconnect between the strong endorsements he received from his Navy SEAL superiors and the denial of his visa for "failure to provide faithful and valuable service" is both mystifying and maddening. This week, poring through photos of himself with American buddies in the field and letters from commanders citing his service "above and beyond the call of duty," he sighed and shook his head.

"What more could I have given? Why was I punished?" he asked. "I may never know the answer."