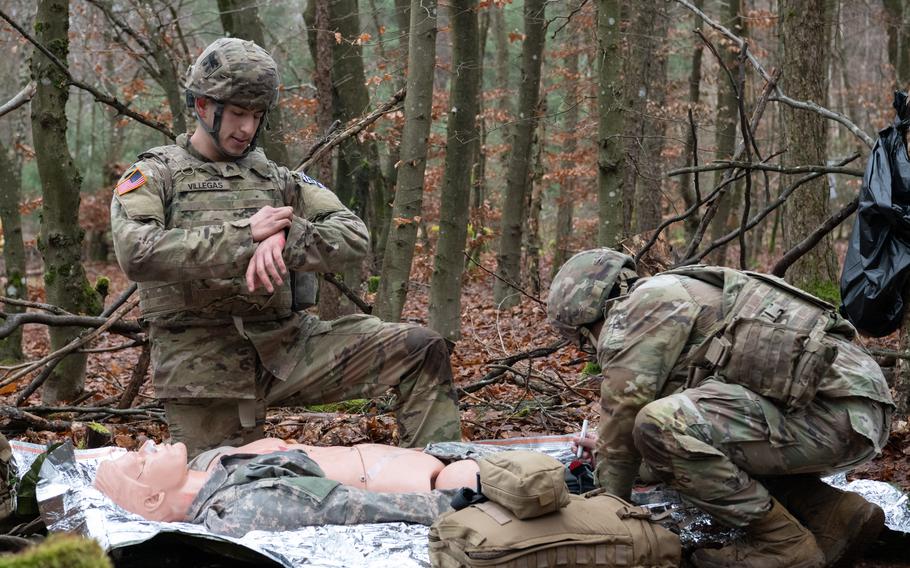

Sgt. Andrew Villegas, left, and Cpl. Billy Wiggins, combat medics assigned to the 52nd Air Defense Artillery Brigade, participate in the Europe Best Medic Competition in Landstuhl, Germany, Dec. 11, 2024. (Phillip Walter Wellman/Stars and Stripes)

LANDSTUHL, Germany — This year’s competitors for the title of best Army medics in Europe faced extended treatment of battlefield casualties as one of their biggest tests, a focus reflecting the rise of more powerful U.S. adversaries.

The annual Europe Best Medic Competition concluded Thursday at Breitenwald Range in Landstuhl, putting a capstone on a three-day ordeal in which participants faced the crucible of what’s known as prolonged critical care.

Organizers said their emphasis on lengthier field treatment was a relatively new facet of the competition that anticipated wars in which U.S. forces no longer control the skies.

“We are not going to be able to evacuate (the wounded) as quickly. That’s what’s expected; that’s what the war in Ukraine is showing us,” Capt. Andrew Kennedy, who oversaw the competition and helped organize it, said Tuesday. “So we’re developing more considerations for near-peer conflict and what medics will need.”

Sgt. Brayden Chapman and Sgt. Heith Walston of the 173rd Airborne Brigade in Vicenza, Italy, were announced Friday as the overall winners.

A team made up of 2nd Lt. Nathan Istre and Capt. Taylor Hughes of Public Health Command Europe was the top finisher among the entrants from Medical Readiness Command, Europe.

Next year, the four of them will take part in the U.S. Army Best Medic Competition, matching up with counterparts from across the globe.

Army 2nd Lt. Nathan Istre, left, and Capt. Taylor Hughes, assigned to Public Health Command Europe, move a mannequin under a barbed-wire obstacle during the Europe Best Medic Competition in Landstuhl, Germany, Dec. 11, 2024. (Phillip Walter Wellman/Stars and Stripes)

The competition featured 22 teams of two Army medical professionals, along with a team of two Czech soldiers. A central event required teams to keep two severely wounded mannequins alive for two-and-a-half hours in near-freezing temperatures.

The high-tech mannequins simulated blood flow and breathing, creating a realistic challenge. Most teams lost at least one mannequin during the event, which Kennedy said was expected.

“The goal is to push participants to the edge of their medical ability,” he said, adding that many of the competitors had little or no prior training in prolonged critical care.

During counterinsurgency campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan, the U.S. relied on air superiority to rapidly evacuate wounded troops from the battlefield to field hospitals.

However, military officials agree that a future conflict against an adversary with advanced capabilities would likely delay transportation of the wounded from the battlefield, forcing medics to care for them for hours or even days.

While all Army medical personnel are trained in basic life-saving skills, many lack experience in advanced techniques like prolonged critical care but compete in the annual test anyway.

“This has definitely been a wake-up call for me,” said 2nd Lt. Aden Rothmeyer, a health services administration officer with the 2nd Cavalry Regiment in Vilseck, Germany.

Rothmeyer and his teammate, Spc. Daniel Buenos Aires, managed to keep one mannequin alive for the entire two-and-a-half-hour test. The other mannequin, which had burns, gunshot wounds, exposed brain matter and a missing limb, was deemed dead after about 30 minutes.

“Seeing that casualty, I was like, ‘Holy crap, this is something we might actually have to deal with,’” Rothmeyer said. “I have to go back and make sure my platoon can train at this level. Everybody has to step up their game.”

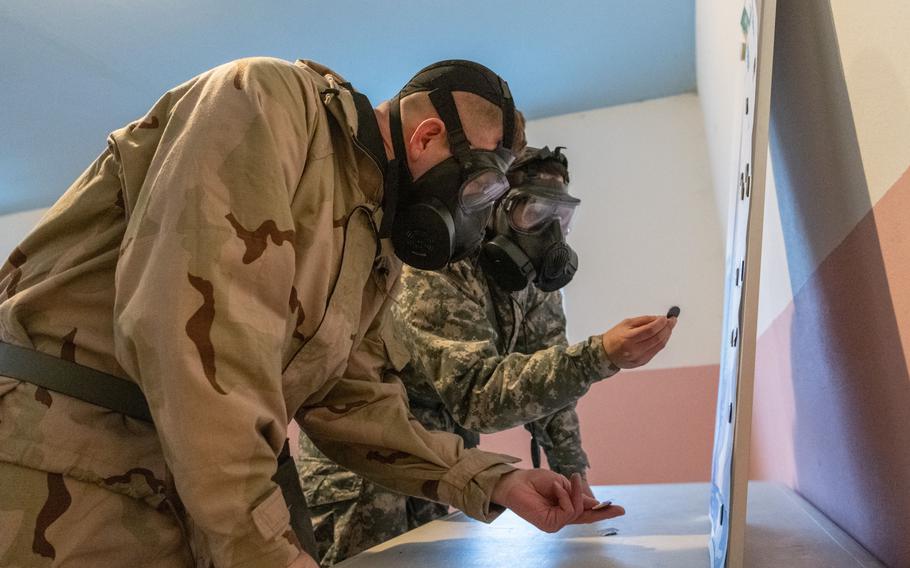

Challenges in the competition extended beyond medical skills and included a shooting contest, nighttime land navigation and problem-solving inside a gas chamber.

Individual units determine their own competitors, with some selecting seasoned medics and others opting to send younger personnel to build their skills.

Soldiers wearing gas masks complete an exercise in a gas chamber during the Europe Best Medic Competition in Landstuhl, Germany, Dec. 11, 2024. (Phillip Walter Wellman/Stars and Stripes)

Despite the uneven playing field, organizers said the competition is meant to provide valuable feedback for all participants and their units. The incorporation of prolonged critical care into the competition this year indicates its growing relevance, they said.

Among the most physically demanding events was the tactical combat casualty care and evacuation scenario, which required teams to carry a mannequin weighing as much as an adult male through an obstacle course on a stretcher.

The course featured barbed wire and cement barriers that contestants had to crawl under and over.

After completing the course Wednesday, just hours after placing second in a 10-mile ruck march, Sgt. 1st Class James Miller of the 173rd Airborne Brigade described the event as an effective way to keep soldiers battle-ready.

“We have to stay competitive,” Miller said. “Seeing someone beat you doesn’t feel good. It drives you to push harder, to be better.”