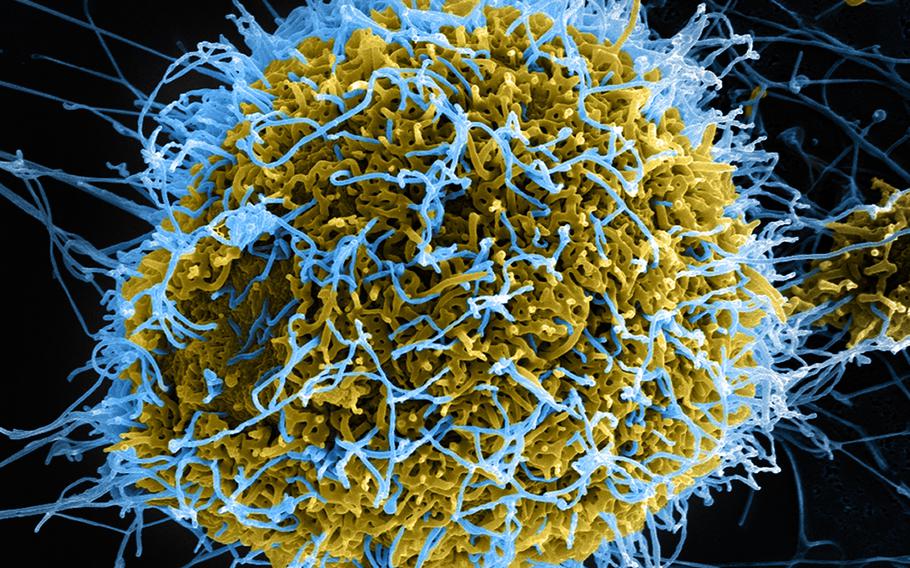

Colorized scanning electron micrograph of Ebola particles. Filamentous Ebola virus particles (blue) are budding from a chronically infected VERO E6 cell (yellow-green), in this image captured and enhanced by the NIAID Integrated Research Facility in Ft. Detrick, Maryland. (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases)

A few months after Russia began its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, satellite imagery captured unusual activity at a restricted military research facility nestled among the birch forests northeast of Moscow.

The Russian site, called Sergiev Posad-6, had been quiet for decades, but it had a notorious Cold War past: It had once been a major research center for biological weapons, with a history of experiments with the viruses that cause smallpox, Ebola and hemorrhagic fevers.

Satellite imagery over the next two years — collected by commercial imaging firms Maxar and Planet Labs — shows construction vehicles renovating the old Soviet-era laboratory and breaking ground on 10 new buildings, totaling more than 250,000 square feet, with several of them bearing hallmarks of biological labs designed to handle extremely dangerous pathogens.

There has been no sign such weapons have been used in the Ukraine conflict, but the construction of new labs at Sergiev Posad-6 is being closely watched by U.S. intelligence agencies and bioweapons experts amid worries about Moscow’s intentions as the conflict grinds through its third year.

The images showed multiple signatures that, when combined, indicate a high-containment biological facility: dozens of rooftop air handling units, layouts consistent with partitioned labs, underground infrastructure, heightened security features and what appears to be a power plant.

In recent weeks, Russian officials have publicly confirmed that the scientists will use the labs to study deadly microbes such as the Ebola viruses, in an effort to strengthen the country’s defenses against bioterrorism as well as future pandemics. Under Centers for Disease Control guidelines, U.S. research on Ebola is restricted to laboratories rated as “biological safety level 4” (BSL-4), equipped to handle the most lethal and incurable kinds of viruses and bacteria.

The Russian Ministry of Defense did not respond to a request for comment.

Here are the key findings, based on an analysis of satellite images and interviews with current and former U.S. intelligence officials — as well as military, biodefense and satellite imagery experts:

Four buildings have an unusually large amount of air-handling equipment, at a scale typically associated with high-containment laboratories.

BSL-4 labs require precise air pressure control, robust filtration, backup air equipment, and separate systems for lab and non-lab spaces to protect scientists from contagious microbes.

The air in a BSL-4 lab must be replaced 12 to 15 times per hour to maintain negative pressure, said Andrew C. Weber, a former top Pentagon official for nonproliferation who spent years investigating Soviet bioweapons facilities in the 1990s.

Soviet-era labs at the Sergiev Posad-6 facility that worked on weaponization of viruses similar to Ebola had a “very secure air-handling system” to keep pathogens from escaping, said Michael Duitsman, an expert in Russian and Soviet missile technology and nuclear nonproliferation at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies.

The site also includes a building with tall exhaust stacks that several experts believe to be a small power plant.

A power plant independent of local energy infrastructure is critical to maintain the temperature and air circulation that a BSL-4 requires, Weber said.

Satellite images taken in April and May 2023 reveal the construction of a 36-foot-wide underground tunnel that links the labs and power plant — enough room for vehicles and personnel to travel in a secure and environmentally controlled space, as well as pipes to convey steam that can be used for heating as well as for autoclaves that sterilize contaminated laboratory equipment.

Images taken before the roof construction also reveal a complex design with clusters of compartmentalized rooms that experts said were likely laboratory antechambers for decontamination. One expert said the layout was “consistent with lab design,” and most likely indicated “maximum containment” laboratories.

U.S. officials and arms control experts, noting the secrecy surrounding the military facility, say they are worried about how Russia intends to use the new labs. “This is where they weaponized smallpox,” Duitsman said. “New technologies could supercharge the capabilities of a revived program.”

Intelligence officials and biodefense experts say it is impossible to tell from satellite photos whether Russia plans to carry out offensive bioweapons research. A laboratory equipped to study the deadly Ebola virus for vaccine development may appear outwardly identical to one that conducts research on weaponizing the strain.

Weber said he was troubled by Moscow’s decision to embed the new research capabilities within the Russian military in a highly secretive location notorious for its past role in bioweapons research.

“The upgrades are consistent with this secure, top-secret military biological facility’s historic role in developing viral biological weapons,” said Weber, a senior fellow at the Council on Strategic Risks, a Washington think tank.

The new campus has several hallmarks of a Russian high-security site that are consistent with the precautions taken at a BSL-4 facility, five experts told The Post. The checkpoints, road design, tree clearing, and nested fencing tightly control movement and allow for monitoring and surveillance, according to experts. “It’s called an onion layer of defense,” said William Goodhind, a military imagery analyst at Contested Ground. “The more layers there are, the less likely you are to have it defeated.”

Its security perimeter was cleared of trees to maintain clear lines of sight, in a manner consistent with defenses at other top-security Russian military sites, Duitsman said. “Their nuclear weapons storage sites are in forests, but there are clear perimeters around them so that they can see anyone who tries to approach.”

A checkpoint upgraded in August 2022 and one built in February 2024 control entry to the campus.

One main road restricts movement to a set path. A separate road around the site’s perimeter could allow for security patrols.

New security fences connect to existing security barriers, which compartmentalize the new buildings within Sergiev Posad-6’s laboratory zone.

Additional fencing bifurcates this zone from the area containing housing and administration facilities.

Weber linked the expansion in military bioresearch to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s oblique threats to use nuclear weapons in the event of an escalation in the Ukraine conflict. Biological and chemical weapons are outlawed under international treaties, but Moscow appears to be warning its adversaries that it could unleash unconventional weapons if pushed, Weber said.

“Putin has been brandishing nuclear weapons openly and in the press,” Weber said. “But because they will never admit to having biological weapons, the way to signal is to talk about these facilities. The subtle hint there is, ‘Hey, we’ve got this capability. And don’t think we won’t use it.’”

In an April interview with the Russian military newspaper Red Star, the labs’ military commander, Sergey Borisevich, described the facility as the “backbone of the country’s biological defense system.” Borisevich said the facility was designed to create the “medical means to protect troops and the population from biological weapons.”

In the satellite photos, ground-clearing becomes visible in May 2022, a few months after the start of Russia’s full-scale Ukraine invasion, and around the time of a Kremlin-led disinformation campaign that accused the United States of helping Kyiv create a secret bioweapons program. Russian officials filed a formal complaint at the United Nations in June 2022, and suggested, without evidence, that Ukraine was preparing to use biological weapons against Russian forces.

The Soviet Union used a similar playbook in justifying a massive bioweapons program in the 1970s and 1980s. Soon after the United States outlawed biological weapons and destroyed its Cold War stockpile in the late 1960s, Soviet leaders began putting tens of thousands of military and civilian scientists to work on an expanded program to weaponize diseases such as anthrax, smallpox and the bubonic plague. Russian defectors, including several of the program’s top scientists, revealed the existence of the illegal weaponization project in the late 1980s. Many said the work was driven by a conviction — promoted by Kremlin officials — that Western countries were making the same weapons in secret.

Intelligence officials see a similar strategy at work in Russia’s recent use of chemical weapons that are also banned under international law. The United States and other countries have accused Moscow of making outlawed nerve agents and using them in assassination attempts against opposition leaders and defectors, including Sergei Skripal, an exiled Russian military intelligence officer who was poisoned by Russian operatives in 2018 at his home in Salisbury, England. The State Department accused Russia in an April report of repeatedly using banned chemicals as weapons in Ukraine, citing videos posted by Russian soldiers showing chemical grenades dropped on Ukrainian troop positions.

Officially, the Kremlin denies that such weapons exist in Russia.

Former Russian president Boris Yeltsin acknowledged in 1992 that the Soviet Union had built a bioweapons arsenal, but the Kremlin later rescinded the statement, insisting that no such weapons had ever been made. Under Putin, Moscow has frequently accused the United States and its allies of plotting to use biological weapons against Russians, without evidence. The United States ended production of biological and chemical weapons in 1969 and completed the destruction of its Cold War bioweapons stockpiles under civilian oversight in 1972.

“The Russians have never been transparent about the Ministry of Defense facilities,” said Mallory Stewart, the assistant secretary for the State Department’s Bureau of Arms Control, Deterrence, and Stability. “It raises questions about what they’re hiding.”

The flurry of lab construction has injected new life into a military complex that had long been regarded as a sleepy relic of Russia’s Soviet past. The research center about 60 miles northeast of central Moscow was created by the Red Army in the 1950s as one of the Soviet Union’s “closed” military cities clustered around secret nuclear, chemical and biological weapons factories and research facilities, each with heavily restricted access, including a ban on foreign visitors.

The walled compound originally known as a Zagorsk-6 was built on the outskirts of Sergiev Posad, a city of 110,000 famous for its 14th Century monastery and onion-domed churches. Up to 6,000 scientists and family members lived inside the walls, in government-built apartment complexes with playgrounds and at least one school.

“The Soviet Biological Weapons Program,” a 2012 book by Milton Leitenberg and Raymond Zilinskas that provides the most comprehensive public survey of Soviet bioweapons facilities, identifies Zagorsk-6 as the center for military research into pathogenic viruses, particularly the variola virus, which causes smallpox. One of the facility’s accomplishments was the development of a more efficient method of reproducing variola virus using cell cultures, Leitenberg and Zilinskas wrote.

One of the Russian military units that operates at Sergiev Posad, the 48th Central Scientific Research Institute, is under U.S. sanctions for its alleged involvement in illegal weapons activity, including assisting the development of chemical weapons used in the Skripal assassination attempt.

Satellite imagery reveals upgrades within the civilian zone of the compound where scientists are housed, including a new structure erected starting in August 2022 and renovations on an existing building in the summer of 2024.

Work in Sergiev Posad-6 appears to be ongoing. Russian news reports and published scientific studies have described research on infectious diseases since the end of the Cold War. In 2020, scientists there helped to develop Sputnik-V, Russia’s first vaccine for battling the covid-19 pandemic.

But most of what goes on inside has been obscured from sight. It is one of only three Russian weapons facilities that never granted access to international experts during the 1990s, when Moscow actively sought Western help to prevent Soviet-made weapons and components from being stolen. An American-led team in the 1990s set up a workshop outside the walls of Sergiev Posad-6 to train Russians on how to install upgraded security systems, but they were never allowed inside the gates.

U.S. intelligence analysts have concluded that the facility probably still possesses frozen collections of viruses that were studied and tested during the Soviet era. “The Soviet program was absorbed, not dismantled, by the Russian Federation,” the State Department said in 2022 statement to the United Nations, “and that program has continued and evolved.”

Borisevich, the institute’s military commander, said the Kremlin urgently needed to upgrade its biodefense capability to prepare the country for attacks by Russia’s adversaries, including foreign governments and terrorist groups. He referred specially to the Ukraine conflict — what Moscow terms a “special military operation” — and to the allegations of a U.S.-Ukrainian bioweapons program in describing Russia’s motivation for deepening its research into biological threats.

“The facts of biological experiments conducted on the territory of Ukraine, which were revealed during the special military operation, are a clear evidence of the urgency of the tasks that, as 70 years ago, the scientists of the Institute are facing today,” he said in the April Red Star interview.

The comment suggested to some U.S. experts that administrators at the facility may at least be contemplating experiments with engineered strains. In the Soviet Union’s waning years, scientists sought to cultivate new strains of plague bacteria that were genetically modified to increase resistance to antibiotics, according to Russian scientists who worked on such programs and later defected to the West.

State Department officials have ridiculed Russian allegations that the United States is working on biological weapons, alone or with partners. But U.S. officials and experts say Russian scientists may legitimately believe that the threat exists, and thus feel justified in creating and testing new weapons.

“I would not be surprised if some influential segment of the Russian national security community has drunk the Kool-Aid and really believes that the United States really is developing bioweapons,” said Gregory Koblentz, director of biodefense programs at George Mason University’s Schar School of Policy and Government.