Members of the Alpha unit at the Avdiivka coke and chemical plant. (Wojciech Grzedzinski/The Washington Post)

AVDIIVKA, Ukraine — The Russians were already so close that the road to the Avdiivka coke and chemical plant was only dared taken at night. Vehicle headlights were shut off and covered, hoping to prevent glare visible to an enemy drone hovering overhead.

As fighters from the Ukrainian Security Service’s “Alpha” special forces branch drove through the blackness with night-vision goggles last week, Washington Post journalists riding along saw only an occasional flash of light on the horizon — from yet more explosions in the besieged city, which is now the focus of the most pitched fighting in the war. A Russian drone above could not be seen, but a handheld device confirmed its presence.

The ruined coke and chemical plant, once an economic pillar in Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region, is likely to be the last Ukrainian stronghold in Avdiivka, which has been embattled since 2014. Ukrainian troops say it is just a matter of time before they will have to surrender the city, and on Thursday the military said a partial withdrawal has already begun.

Avdiivka potentially poses a first critical test for Ukraine’s new commander in chief, Col. Gen. Oleksandr Syrsky, who was elevated last week by President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and must decide if and when to admit defeat and withdraw. Many troops accuse Syrsky, who previously led Ukraine’s ground forces, of waiting too long to do the same last year in Bakhmut, another eastern city, when it was under siege last year.

Capturing Avdiivka would mark Moscow’s most significant battlefield victory since the failure of a Ukrainian counteroffensive last year — and would be the clearest sign yet that Russian forces are regaining the initiative as Kyiv runs short of soldiers, weapons, ammunition, morale and money.

Located just 15 miles outside the occupied regional capital of Donetsk, Avdiivka has more strategic value for Russia than Bakhmut. Pushing Ukrainians back from Donetsk city and its residential areas, which Russian President Vladimir Putin claims Ukrainian forces shell regularly, could boost the spirits of Moscow’s forces as the grinding war nears its two-year mark.

“It all comes down to logistics,” said Serhiy, 41, an infantry platoon commander with Ukraine’s 53rd Brigade fighting in the area. “Roads, interchanges, everything: A lot of logistics is tied up in the streets of Avdiivka.”

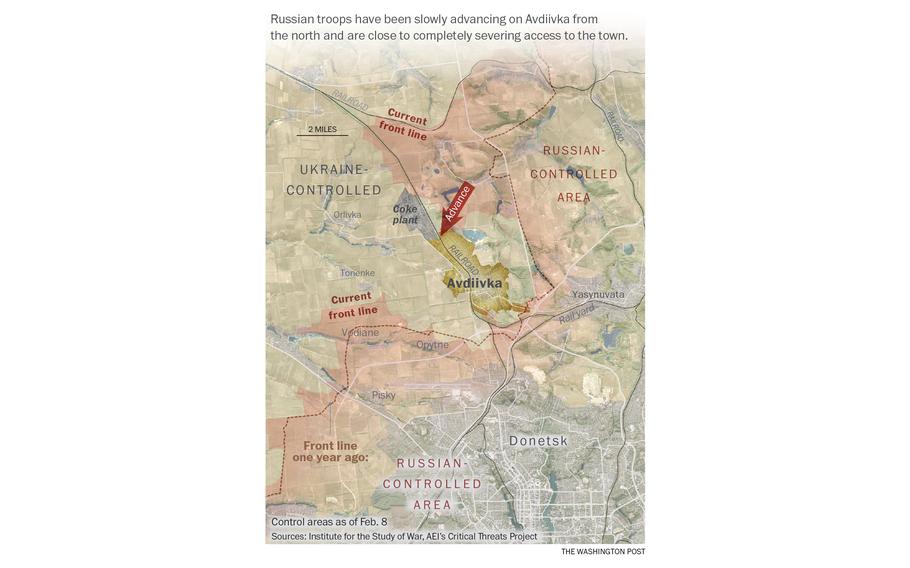

(Laris Karklis/The Washington Post)

Russia captured Bakhmut in May. Ukraine’s military and political leadership said continuing to defend Bakhmut cost Russia tens of thousands of casualties. But the battle also depleted Ukraine’s forces.

While a full withdrawal from Avdiivka now seems likely, when Post journalists visited last week, fresh forces from assault brigades were being rotated in to help fend off the Russian attacks and continue Avdiivka’s defense.

Some Ukrainian soldiers are comparing the fortresslike coke and chemical plant to Azovstal, the vast iron and steel plant in Mariupol where Ukrainians made a final defensive stand before surrendering that city in 2022. Dozens of Ukrainians were taken prisoner at Azovstal, but “storming the coke plant will be very difficult and probably not make sense,” said an Alpha drone pilot in Avdiivka, whom The Post agreed to identify only by his call sign, Vitamin.

“They will try to bypass it and encircle it, and then that’s it. Our forces will be forced to withdraw,” he said.

(The Washington Post)

Earlier this month, Russians advanced into Avdiivka itself, setting off street fighting amid the city’s mostly ruined buildings. When Post journalists visited the plant for a night and a day last week, a team from the Alpha unit, which is formally known as the Ukrainian Security Service’s Center of Special Operations “A” branch, was using a section of the abandoned chemical plant as a base to launch first-person view, or FPV, drones rigged with explosives — as well as an onboard camera that allows the operator to see what the drone sees.

Minutes after reaching the plant, the Alpha fighters were on guard for any noises — even those of mice running across the stone floor — for fear that it could be a Russian soldier who had unexpectedly slipped inside. At the sound of someone descending the stairs, an Alpha marksman whose call sign is Mirage stiffened.

“They’re walking too loudly to not be one of ours,” said Sergiy Stakhovsky, a former professional tennis player who is now a member of the Alpha special forces.

The plant used to be a symbol of the eastern Ukrainian economy — the largest producer of coke, a coal-based fuel, in Ukraine and owned by Ukraine’s richest man, Rinat Akhmetov. Like the Donbas region itself, much of it is in ruins now after years of war.

In the fall, the Russians often pounded it with some 20 airdropped bombs per day, Vitamin said. As Vitamin and his team were working from the plant last week, an incoming shell came through the roof near the area they used as their drone launchpad, missing everyone by about 350 feet. But its underground hideouts and sturdy concrete foundation still make it a favorable defensive base for the Ukrainians.

In one area of the plant, just two members of the 47th Separate Mechanized Brigade were sleeping — though there were enough bunks for a dozen people. It was bitterly cold, even with a small fire burning. At 2 a.m., one white-haired man, Yura, woke up at the sound of his alarm. He took a deep breath before standing up from his bunk, which was decorated with a child’s painting of a cat. He then brewed hot water over a propane tank burner to make his coffee, adding four sugars. His fellow soldier was still loudly snoring nearby.

“Rats will crawl on him and wake him up eventually,” Yura said.

Ukraine’s ammunition shortage is felt particularly hard here, as shocks from incoming Russian artillery fire rattled the building far more often than the sounds of outgoing fire. The periodic blasts were followed by birds’ cawing as they flew away from the area.

The Russians “are currently trying to exert pressure on the right flank of the coke plant, and they are succeeding,” Vitamin said. “They press on, disregarding losses, and our forces are forced to retreat under the pressure.”

The rise in quantity of cheap self-destructing drones on both sides of the fight has made any activity perilous. For the Ukrainians, FPV drones are a more accurate alternative to shells, and they can be made domestically — more quickly and easily than artillery ammunition, which Kyiv still depends on the West to produce and provide. Each drone can cost as little as $400. But the Russians have FPVs, too — and more of them — largely entrenching both forces, who fear that even a single soldier walking around will be targeted.

The Ukrainians used to save their FPV drones for bigger targets — tanks, personnel carriers, artillery systems and so on — but now there is a green light to attack even a small group of enemy infantry. The point is to use the weapons to stop the regular small-group assaults while saving artillery for other targets.

Watching a feed of several reconnaissance drones flying over Avdiivka, Vitamin was frustrated that the Russians were not showing themselves for exactly that reason. “Nobody wants to … die today,” he said.

He pointed out a Russian soldier sprinting from one house to another, pleased that he was scared. This is a part of what Kyiv is calling an “active defense” strategy, finding ways to inflict damage on the invaders while in a defensive posture.

“Here, our active defense comes into play — when holding Avdiivka makes no sense, but we still hold it,” Vitamin said. “Because we kill many more of the enemy here than [they kill] our forces. We destroy their reserves.”

Maintaining constant contact with another unit in the area, Vitamin tracked a group of Russians entering a house and then waited for them to exit. Three ran out. Directing the drone while wearing goggles that gave him the camera’s view, Vitamin descended and landed between two, likely wounding both men.

“Go to hell!” Vitamin screamed after the reconnaissance feed confirmed a successful strike.

But the next day, the Ukrainian defense continued to deteriorate. The Russians reached a part of the coke plant but were pushed back. By Wednesday, the road Alpha used to get to the plant was under Russian fire control.

Anastacia Galouchka in Kramatorsk, Ukraine, and Serhii Korolchuk and Serhiy Morgunov in Kyiv contributed to this report. Maps by Laris Karklis.