Europe

AnalysisPutin, flexing UN veto, takes aim at global rules

The Washington Post October 20, 2023

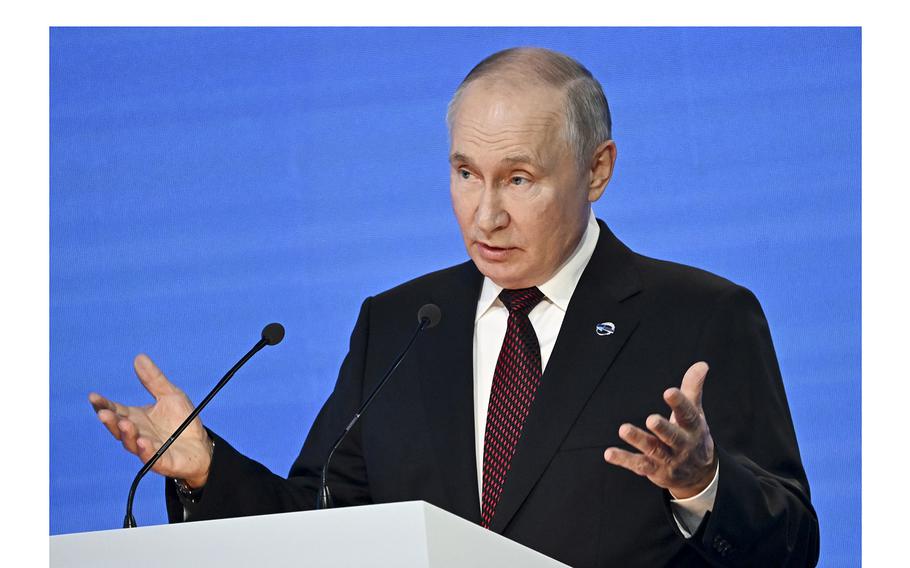

Russian President Vladimir Putin gestures while speaking at the annual meeting of the Valdai Discussion Club in the Black Sea resort of Sochi, Russia, on Oct. 5, 2023. (Grigory Sysoyev, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool via AP)

RIGA, Latvia - At a recent public policy forum, President Vladimir Putin extolled his “new world” and rejected a global rules-based order as “some kind of nonsense.”

“What rules?” Putin snapped at a meeting of the Valdai Discussion Club in Sochi on Russia’s Black Sea coast. He dismissed the rules-based international order as Washington’s “openly boorish way” of telling Russia how to behave. The era of global rules “is long over and will never return,” Putin said. “Never!”

Previously, the Russian leader has called the system “rigged” and “designed for fools.”

Moscow’s rejection of a rules-based international order is evident in its war in Ukraine - where it has violated borders, killed civilians and targeted infrastructure, and where there is evidence its forces committed torture and abducted children. It is also evident in international diplomacy, most strikingly at the United Nations, where Russia has used its veto in the Security Council to defy calls for its withdrawal from Ukraine.

Russia’s war against Ukraine - in which a permanent member of the Security Council blatantly violated the U.N. Charter and can unilaterally block any substantive action to end the hostilities - has undermined the Security Council’s legitimacy and triggered a renewed clamor for reform.

Russia claims to support such reform and a bigger role for the Global South in world affairs. But the Kremlin prizes its Security Council veto, along with its nuclear arsenal, as global status symbols. Other permanent Security Council members, including the United States, have also resisted meaningful reform while paying lip service to the idea.

“Basically, the veto power says to everyone, ‘There’s nothing you can do without our say-so. It’s having that veto power that sets you apart from the rest,’” said Bobo Lo, author of “Russia and the New World Disorder.”

Lo argues that Russia’s Security Council tactics reflect Moscow’s self-image as a great power able to shatter international norms and upend the global order in its favor.

Putin’s visit this week to China, where he was an honored guest at a summit celebrating President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road global infrastructure initiative, highlights the determination of the two autocratic leaders to lock arms against the United States and the rest of the West.

A Russian victory in Ukraine would be a major defeat for an international order - evidence that territory can be seized by force, and smaller nations are subject to the whims of larger powers.

“Putin of course is trying to undermine the world order because this for him is the only strategy to survive,” the exiled Russian tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovsky said in an interview.

Some analysts believe that an era of disorder, conflict and fragmentation has already begun.

Putin and his foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, frequently extol a new multipolar world, with vague words about democratizing the Security Council. But their goal, analysts say, is to shape the United Nations and other bodies to suit Moscow’s own interests.

“We are faced, in essence, with the task of building a new world,” Putin told the Valdai meeting. “Russia was, is and will be one of the foundations of the world system.”

But to Russia, “democratization doesn’t mean that New Zealand becomes as important as Russia or America,” Lo said. “Democratization of international relations means that the West and particularly the United States doesn’t get to call the shots.”

The U.N. Security Council has failed for decades to prevent conflicts, due largely to the veto power of the five permanent members. But Russia could sow more chaos if it chooses, said a senior member of Russia’s diplomatic circles.

“Russia has a lot of opportunities to complicate the position of the West in many different parts of the world,” he said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to offer a candid assessment. “There are possibilities in Africa, in the Middle East, in East Asia and Latin America.”

Changing the U.N. Charter is all but impossible, requiring unanimity among the five permanent Security Council members as well as a two-thirds majority vote in the General Assembly.

“The Security Council has become the most discredited multilateral institution in the world,” Lo said. “And I can’t see it getting any better. U.N. reform is almost an oxymoron.”

Critics say the U.N. has been discredited not only by Russia but also by the Bush administration’s justification of the Iraq War with false assertions that Baghdad was hiding weapons of mass destruction.

The United States has also been criticized for using its veto to shield Israel from criticism over its treatment of Palestinians in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. Washington recently vetoed a resolution put forward by Brazil calling for a pause in the Gaza fighting to allow humanitarian aid deliveries because it “did not mention Israel’s right to self-defense.”

In an address to the Security Council, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky last month called for Russia to be stripped of its veto. Others insist that Russia, legally, should never have inherited the Soviet Union’s permanent seat. Technically, they say, that change required amending the U.N. Charter, which never happened.

Russia’s use of the veto has been more sweeping than that of any other nation, blocking a Security Council resolution demanding its withdrawal from Ukraine and a resolution condemning its illegal annexation of four territories in Ukraine.

For all of Moscow’s talk of multilateralism, Russia has stymied other key Security Council votes since the invasion, vetoing sanctions against individuals in Mali who violated a 2015 peace deal, vetoing humanitarian aid to civilians in Syria and preventing a unified response to North Korea’s ballistic missile tests.

In the past Russia has blocked an investigation into Syria’s repeated use of chemical weapons against its own population and an international tribunal on the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, which was shot down with a Russian-supplied weapon as it flew over eastern Ukraine in 2014.

Russia also vetoed a 2007 resolution calling on the Myanmar military junta to stop persecuting minority and opposition groups.

Since the founding of the United Nations after World War II, Russia and its predecessor, the Soviet Union, have used the veto 154 times, more than any other state, including 26 times since Putin returned to the Russian presidency in 2012.

The United States has done so 88 times, including 19 times since the fall of the Soviet Union and just four times since 2012. In September 2022, Washington vowed to refrain from using the veto “except in rare and extraordinary circumstances.” Britain and France have not used their vetoes since 1989.

Richard Gowan, an expert on the U.N. with International Crisis Group, said Russia’s vetoes could lead to increased discord and paralysis, stymying peacekeeping and humanitarian missions.

“Russia is becoming considerably more assertive in the council, more willing to be spoilers than it was in 2022,” Gowan said. “There’s a sense that we’re getting to the point where the Russians will just block more and more, as the overall diplomatic mood gets more and more sour.”

Gowan said he fears breakdowns over crucial global issues, such as the framework for enforcing and monitoring U.N. sanctions on North Korea over its nuclear program.

Putin’s rhetoric about Western hypocrisy, however, often resonates with leaders in Global South, many of whom do not want to take sides and are disillusioned by Western failures on climate change, food security, the covid-19 pandemic and economic development. The U.S. veto on Gaza humanitarian aid probably will reinforce discontent with Washington in the Global South.

The member of Russian diplomatic circles said Russia and China were increasingly distancing themselves from the West’s positions on North Korea, creating a divide between the United States and its allies on one side, and Russia, China and North Korea on the other.

“The risks and dangers will probably grow,” he said.

A former United States diplomat, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive international relations, said Russia’s objective is to narrow the interpretation of global rules and treaties, some signed by the Soviet Union, especially its past commitments to rights and democracy.

“They’re trying to sell a narrative in which the rules-based international order is some artificial creation of the United States and its allies, imposed on the rest of the world,” the former diplomat said. “That’s garbage. The rules-based international order is rules that were drawn up by multilateral negotiation of all those people who were going to be living by those rules, and that includes Russia, and that includes the Soviet Union.”

Belton reported from London.