Europe

Ukraine is now the most mined country; it will take decades to make it safe

The Washington Post July 24, 2023

Mines and unexploded rockets next to a destroyed bridge on the way to Kherson, Ukraine, in November 2022. MUST CREDIT: Photo for The Washington Post by Wojciech Grzedzinski. (Wojciech Grzedzinski)

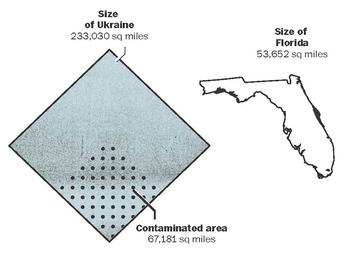

In a year and a half of conflict, land mines — along with unexploded bombs, artillery shells and other deadly byproducts of war — have contaminated a swath of Ukraine roughly the size of Florida or Uruguay. It has become the world's most mined country.

The transformation of Ukraine's heartland into patches of wasteland riddled with danger is a long-term calamity on a scale that ordnance experts say has rarely been seen, and that could take hundreds of years and billions of dollars to undo.

Efforts to clear the hazards, known as unexploded ordnance, along with those to measure the full extent of the problem, can only proceed so far given that the conflict is still underway. But data collected by Ukraine's government and independent humanitarian mine clearance groups tells a stark story.

"The sheer quantity of ordnance in Ukraine is just unprecedented in the last 30 years. There's nothing like it," said Greg Crowther, the director of programs for the Mines Advisory Group, a British charity that works to clear mines and unexploded ordnance internationally.

Staggering scale

About 30% of Ukraine, more than 67,000 square miles, has been exposed to severe conflict and will require time-consuming, expensive and dangerous clearance operations, according to a recent report by GLOBSEC, a think tank based in Slovakia.

Though the ongoing combat renders precise surveys impossible, the scale and concentration of ordnance makes Ukraine's contamination greater than that of other heavily mined countries such as Afghanistan and Syria.

HALO Trust, an international nonprofit that clears land mines, has tracked, using open-source information, more than 2,300 incidents in Ukraine in which ordnance requiring clearance was discovered. Though events are greatly underreported and the data does not include the results of on-the-ground surveys by HALO Trust or other organizations, it gives a harrowing outline of the problem.

Last week's deployment by Ukrainian forces of U.S.-made cluster munitions, which are known to scatter duds that fail to explode, can only add to the danger.

.jpg/alternates/LANDSCAPE_910/ukraine-mines-f8da1f24-28e4-11ee-ab4b-d68d5fc4c55f%201.jpg)

Volunteers and veterans of the Ukrainian Territorial Defense Forces get a briefing on various types of mines on Feb. 5, 2022, on the outskirts of Kyiv. (Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

Human cost

The explosives have already taken a heavy toll. Between the start of Russia's full-scale invasion in February 2022 and July 2023, the United Nations has recorded 298 civilian deaths from explosive remnants of war, 22 of them children, and 632 civilian injuries.

Civilian deminers, who clear unexploded ordnance and mines from liberated territories, are highly trained and use safety gear. But they are not immune from catastrophic accidents.

Vladislav Sokolov, a deminer for Ukraine's emergency service, told The Washington Post that one of his friends, a fellow deminer, lost a leg while working in a Kramatorsk minefield in 2022. Sokolov and his friend reunited at a meeting of ordnance disposal professionals after he received a prosthetic.

He was "trying to learn to walk" again, Sokolov said.

Dmytro Mialkovskyi, a Ukrainian military surgeon, has been operating on mine injuries since the beginning of the war. On Friday, at a hospital in Ukraine's Zaporizhzhia region, he had to make a gut-wrenching call to save the life of a mine blast patient who was dying of his injuries.

"I realized that this leg is killing him and there is another leg with a tourniquet, too," Mialkovskyi said. "So I had to do a quick amputation of both legs. In 10 minutes."

"I still don't know if he'll survive," he said.

A mine warning sign in a cemetery in Chernihiv, Ukraine, in April 2022. (Wojciech Grzedzinski/for The Washington Post)

Hidden killers

Both sides use mines. Russia heavily mined its front lines in anticipation of Ukraine's ongoing counteroffensive, and has made far more extensive use of widely banned antipersonnel mines.

Small, deadly antipersonnel mines, triggered by the weight of the human body, cannot discriminate between combatants and noncombatants.

Russian forces have used at least 13 types of antipersonnel mines, as well as victim-activated booby traps, Human Rights Watch investigations found. Evidence suggests Ukraine has also used at least one type of antipersonnel mine, a rocket-delivered PFM blast mine, around the Ukrainian city of Izyum in summer 2022.

Antitank mines, which usually require immense weight to detonate, are not internationally banned, though any explosive device that could be detonated unintentionally by a civilian can be considered an antipersonnel mine under the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty, to which Ukraine, but not Russia or the United States, is a party.

Both Russian and Ukrainian forces have used anti-vehicle mines.

The United States included two types of mines in its aid packages to Ukraine: the Remote Anti-Armor Mine System, which uses 155-milimeter artillery rounds to create temporary minefields programmed to self-destruct, and M21 antitank mines, which require hundreds of pounds of force to detonate but do not self-destruct, leading to concerns about later removal.

Mines are not the only type of explosive that pose a threat. Mortars, bombs, artillery shells, cluster munitions and others also become hazards if they do not explode when deployed.

Undoing the damage

Russia's heavily mined defenses, built up over months of stalemate along the front lines, are slowing down the Ukrainian counteroffensive that began last month, damaging Western-supplied battle tanks and infantry fighting vehicles.

Though specialized mine-clearing vehicles are in use, front-line mines are so concentrated that specialized soldiers, called sappers, have had to resort to clearing paths by hand.

Humanitarian clearance operations, which return denied land to local populations after conflict, are extremely slow, tedious and expensive. They are underway across parts of Ukraine, including around Kyiv, the capital, and other areas West of the front lines, where the battle has receded.

Ukraine's contaminated territory is so massive that some experts estimate humanitarian clearance would take the approximately 500 demining teams in current operation 757 years to complete.

Demining teams crawl inch by inch across the terrain, using metal detectors and sometimes explosive-sniffing dogs, excavating every signal, not knowing whether they will uncover a harmless nail or deadly mine.

GLOBSEC estimates that one deminer can only clear 49 to 82 square feet per day, depending on the terrain and concentration of explosives.

The short window for clearance in the spring, after the ground thaws and before farmers plant, leaves little room for disasters like the Kakhovka dam breach in early June, which drastically disrupted clearance efforts.

Farmers in heavily contaminated regions such as Kherson have resorted to visual inspections and rigging tractors with armored plates while planting this year's harvest.

There is a steady market for "dark deminers," who offer hasty and often unreliable clearance without official certification, to clear some of the more than 19,000 square miles of unusable agricultural land.

Demining is not just slow, it's also expensive. The World Bank estimates that demining Ukraine, which costs between $2 and $8 per square meter, will cost $37.4 billion over the next 10 years.

The United States has committed more than $95 million to Ukraine's demining, according to a 2023 State Department report.

(The Washington Post)

How Ukraine compares

Mines as a dark legacy of conflict all over the world, from Cambodia to Kosovo, hint at the challenges Ukraine could face as it rebuilds.

Cambodia, riddled with millions of land mines after decades of conflict, has been subject to ongoing clearance operations for 30 years. Crowther estimates there at least five years of work remains. Tens of thousands of people have been maimed by Cambodia's mines.

Kosovo saw armed conflict in 1998 and 1999. "Kosovo was a six-month war that was a fraction of the scale of this conflict," Crowther said of the war in Ukraine. "It's taken decades."