Europe

AnalysisHow Sweden and Finland could alter NATO’s security

The Washington Post July 12, 2023

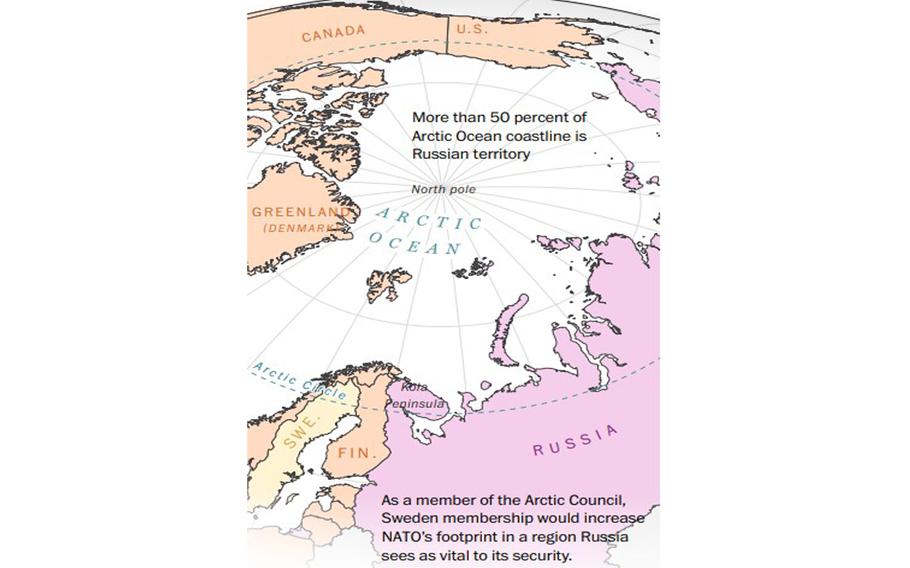

More than 50% of the Arctic Ocean coastline is Russian territory. As a member of the Arctic Council, Sweden’s membership would increase NATO’s footprint in a region Russia sees as vital to its security. (The Washington Post)

Sweden’s path to joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization appeared clearer this week when Turkey, after months of stalling, agreed to let the Scandinavian country enter the alliance.

Over more than 70 years, NATO has grown to an alliance of more than 30 countries. Founded in 1949 to counterbalance the growing power of the Soviet Union, NATO — long a source of tension between the West and Russia — has reasserted itself as a significant and unified force against Moscow since Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Finland, a traditionally neutral nation, officially joined the alliance in April, after submitting a request along with Sweden in response to the war.

Analysts say the move will transform Europe’s security landscape for years to come — and further strain relations with Russia, which opposes the alliance’s eastern expansion.

The addition of both countries could offer the alliance expanded land, sea and air capabilities. Sweden has a strong navy, which would strengthen NATO’s defenses in the Baltic Sea, and builds its own fighter jets.

Finland’s well-funded military maintains mandatory conscription for men. It’s a “whole society approach to thinking about defense,” said Christopher Skaluba, director of the Atlantic Council’s Transatlantic Security Initiative. “They can mobilize hundreds and thousands of their citizens.”

The countries also offer key geographic advantages, which would enhance NATO’s defenses.

Increased Baltic presence

To the South, Sweden and Finland’s membership gives the alliance an edge in the Baltic Sea, a strategic waterway bordered by Russia’s St. Petersburg, as well as some of NATO’s most vulnerable members.

“NATO’s main mission is keep Russia away from the Baltic states,” Skaluba said, referring to Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania. A growing presence on the Baltic sea’s shores could strengthen security for those countries.

“Swedish and Finnish NATO membership would provide NATO with another reinforcement route through the Baltic Sea,” said Carisa Nietsche, an associate fellow for the Transatlantic Security Program at the Center for a New American Security.

In the middle of the sea lies Gotland, a 109-mile-long Swedish island home to medieval ruins and military fortifications. Last year, Sweden announced it would spend $163 million to ramp up its forces on the island, including expanding barracks to house more troops.

An Arctic agenda

Sweden’s accession to NATO would mean an increased presence in the Arctic.

Sweden, along with Finland, is a member of the Arctic Council, an organization overseeing the northernmost parts of the world whose members include Russia, Canada and the United States. With their membership, “Arctic security would continue to climb on NATO’s agenda,” Nietsche said.

As more than 50 percent of Arctic Ocean coastline is Russian territory, it could climb on Moscow’s agenda too. “They see security in the area as a matter of homeland defense,” Skaluba said.

Military missions from the Kola Peninsula — a strategic landmass some 110 miles east of the border where Russia keeps ballistic missile submarines and stores nuclear warheads — are deployed throughout the Arctic. As members, Sweden and Finland could help monitor that activity, but could also increase the risk of escalation.

“The Arctic is generally considered a success story of cooperation among NATO Arctic nations and Russia, but there are concerns that it will increasingly be a contested area in the security realm, something probably more likely with Sweden and Finland becoming NATO nations,” Skaluba added.

A new northern border

Finland’s border with Russia stretches more than 800 miles and is already closely patrolled. The nation’s membership doubles the alliance’s land border. “On one hand, this provides NATO with enhanced deterrence as Moscow would need to defend this border,” said Nietsche. “On the other hand, NATO also must protect this border against a Russian attack.”

The Finns remember the Winter War of 1939-1940, when the country incurred great losses fighting back Soviet forces.

“Their relationship with Russia is defined by mistrust,” said Cristina Florea, a historian of Central and Eastern Europe at Cornell University.

Finland’s membership also brings the alliance closer to the Kola Peninsula. Russia’s Northern Fleet, tasked with patrolling the Arctic, is based on the peninsula as well.