Europe

Ukraine says Putin is planning a nuclear disaster; these people live nearby

The Washington Post July 3, 2023

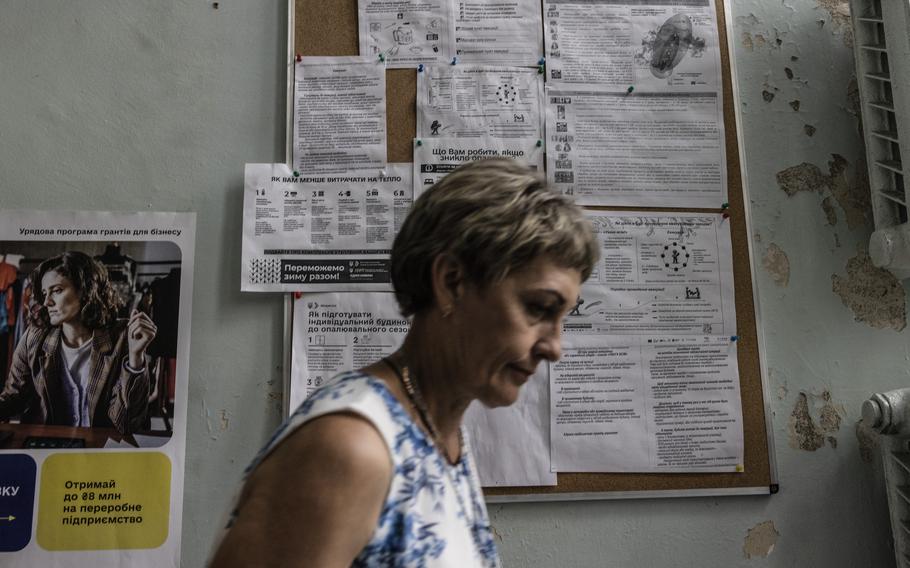

A woman passes by a board last week at the Tomakivka council building with detailed instructions about what to do in case of a nuclear threat. (Heidi Levine/The Washington Post)

TOMAKIVKA, Ukraine — The risk of a major disaster at the nearby Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant terrifies Nadiya Hez, who lives in an area that would probably take the brunt of any deadly radioactive fallout.

The nuclear plant has been in continual danger as Russian and Ukrainian troops trade fire in its vicinity, but the chance of a meltdown has increased sharply since the destruction of the Kakhovka dam just downstream. The June 6 breach unleashed a catastrophic flood and jeopardized the supply of water needed to cool the plant's reactors and spent fuel.

But there have been so many horrors since Russia invaded last year that Hez and others in this Ukrainian town have responded to the threat of a nuclear disaster with a mix of dread and hardened fatalism.

Hez, who is a nurse, at least has iodine tablets on hand to mitigate the effects of radiation poisoning. After days of searching, she located a key to the root cellar outside their Soviet-era home that could serve as a crude fallout shelter for her, her husband and their 1-year-old son, Ihor, should radiation escape from the Russian-held nuclear power plant about 22 miles away. There has been little else to do except wait and focus on the daily hardships the war has already inflicted upon their lives.

"It's horrible — I don't even want to think about it," Hez, 22, said while juggling her baby and several heavy water jugs from a charity's roving tanker truck. The town's municipal water system was knocked out when the dam went.

Warnings from Ukrainian officials and atomic energy experts about a potential disaster in southeastern Ukraine have gained urgency since the dam's breach. Ukrainian officials accuse Russian forces of deliberately blowing up part of the dam, an allegation Moscow has denied.

As far back as October, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky predicted that Russia would destroy the dam. Now, Zelensky and other senior Ukrainian officials have upped the tempo of warnings that Russian forces plan to sabotage the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, the largest such facility in Europe.

Maj. Gen. Kyrylo Budanov, who heads Ukraine's military intelligence, said through a spokesman that Russians have planted explosives next to four of the six reactors and mined the cooling pond used to supply water to chill the reactors and spent fuel.

"There is an extremely high risk of human error or, given the amount of explosives, an accidental detonation," spokesman Andriy Yusov said.

On Friday, the military intelligence agency issued an ominous update, saying that the three Russian supervisors had evacuated and Ukrainian employees signed to work for the Russian state nuclear power conglomerate should depart by July 5. The report also said that personnel remaining behind had been told to "blame Ukraine in case of any emergencies."

Earlier this week, Ihor Klymenko, who heads the Ministry of Internal Affairs, announced training exercises at all levels of government to deal with a possible nuclear disaster. These have included planning for evacuations within a certain radius of the plant, road closures and the creation of checkpoints to screen people for radiation exposure.

For residents unable to evacuate in time, officials have urged sheltering in place, making sure to shut off ventilation and air conditioners and seal up windows with dampened cloth and tape. When outdoors, he said, people should wear masks that can filter out airborne radioactive dust and other particles.

Klymenko and other officials have also urged the public to remain calm — advice that many Ukrainians seem to have taken to heart, despite their country's history with Chernobyl, the site of the world's worst nuclear disaster, and nine years of violent conflict with Russia.

"People are already hardened, resilient," said Yuriy Malashko, the head of the Zaporizhzhia region's military administration.

Russian forces seized control of the nuclear power plant soon after President Vladimir Putin ordered a full-scale invasion in February 2022. All six reactors have since been shut down.

The plant has had several close calls, including from repeated artillery strikes that cut the electric lines maintaining its cooling operations. It is now faced with a dwindling supply of water because of the dam breach.

After the construction of the plant in the 1980s, the reservoir of the Kakhovka dam was used to fill the holding pond cooling its reactors and spent fuel.

As of June 24, the pond's water level stands at about 52 feet — only four meters above the minimum level necessary to cool the plant, said Olena Pareniuk, a senior researcher at Ukraine's National Academy of Sciences who has studied nuclear power plant disasters.

The situation led the International Atomic Energy Agency's general director to conduct an emergency inspection of the nuclear plant days after the dam breach.

In a statement posted on the IAEA's website, Rafael Mariano Grossi said the cooling pond is being replenished with water from a discharge channel at a nearby coal-fired power plant and from a drainage system fed by underground water. At the current rate of evaporation — about four inches a day, Grossi estimated that the plant has enough water for "many weeks." He also said he saw no evidence it had been mined.

Just as concerning, however, is the added pressure on remaining Ukrainian staff, Pareniuk said. Perhaps only 3,000 of its 11,000 employees are left to oversee its operations — "barely enough" to keep the plant safe in a shutdown state and far too few for an emergency.

"The threat of a terrorist attack is high," said a Ukrainian employee still working at the plant, whom The Washington Post is not naming to protect his safety. He said the plant has already reduced the amount of water used to cool the reactors — the hottest of which, according to Pareniuk, is still at about 536 degrees Fahrenheit even after being shut down.

Ukrainian officials and atomic energy experts warn that without sufficient cooling, a reactor's core could overheat, allowing the buildup of an explosive mixture of hydrogen gas and steam that could rupture the containment structure and blow dangerous amounts of radiation into the air. The reactors could melt down within 10 hours or two weeks without water, Budanov said.

What could happen then? Pareniuk and other experts said it is unlikely to be anything like Chernobyl, which blew when the reactor was in active operation. She said the most likely worst-case scenario could be something on scale with the Fukushima disaster in 2011, when fuel in three of the Japanese nuclear plant's four reactors melted down following a massive earthquake and tsunami.

If so, a poisonous cloud could spread across Ukraine, contaminating its agricultural heartland and probably drifting over European neighbors with radioactive particles that increase the risk of certain cancers. Radioactive contamination is likely to reach the Dnieper River, too, flowing into the Black Sea. Depending on water currents, the contamination could touch every country along the Black Sea's shores, Pareniuk said. As a bio-radiologist, she understands in detail what that could mean for her and her 4-year-old child, though they live far away, west of the capital, Kyiv.

"I'm terrified," she said.

So are many people in this small town, located at the edge of the potential 20-mile exclusion zone around the plant. That's the radius of the no man's land that still exists around the Chernobyl plant.

Even before the dam break, Hez had already been through a lot. She gave birth in a hospital bunker in Nikopol as Russian artillery pounded the city. Constant shelling there forced her and her husband, Oleksiy, 23, to relocate here with their baby, where they subsist on state assistance as displaced people and the parents of a child — about $135 a month.

Both have been contacted by the military's draft officials, one of whom told her she would have to put her baby in the care of his grandmother or someone else because her services are needed.

"It's like a horror movie," said Vita Lyashenko, 47, a nurse waiting in line with about 50 other people to collect drinking water in the center of town. Like others, she has been gathering rainwater, recycling water for household chores and going longer without showers since the municipal water system went down after the dam breach. She has also set aside iodine tablets, extra water and tape to seal her windows against radioactive fallout.

Olena Mykytiuk, 59, who lives on disability while caring for her ailing husband, said she, too, has iodine pills but isn't sure whether she wants to take them. She also worries about what might happen to her chickens.

"We don't know how to prepare ourselves for radiation," Mykytiuk said. "We are watching the news, and we know all they need to do is to press a button."

———

The Washington Post's Serhii Korolchuk and Kamila Hrabchuk contributed to this report.