Europe

Bloodied Wagner fighters captured in Ukraine recount path from prison to war

The Washington Post February 23, 2023

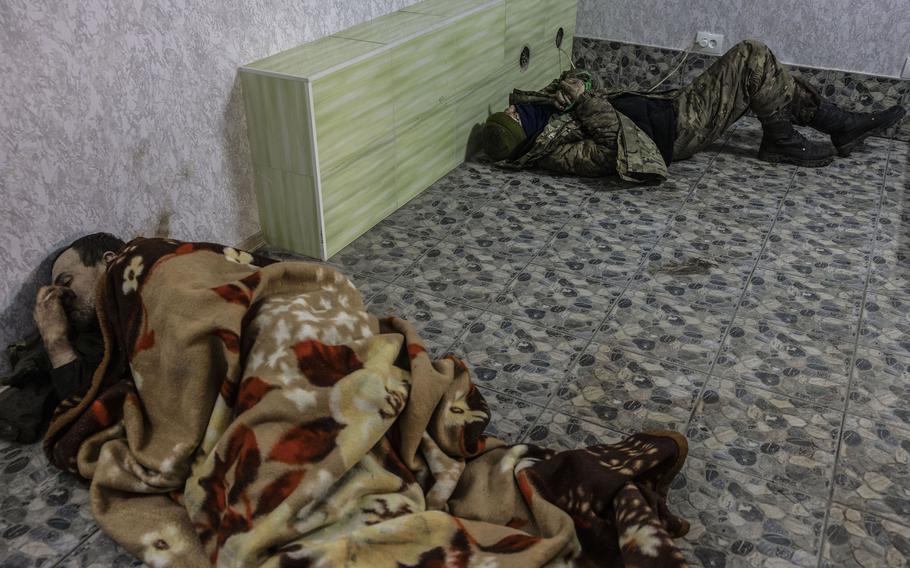

DONETSK REGION, Ukraine — The two men lay on the dirty tile floor of an empty office, still in their bloodied combat fatigues and bandages. One dozed without a pillow under a blanket; the other stretched out with a tourniquet strapped above the knee of his blood-soaked pants.

The men were two of three Russian fighters with the Wagner mercenary group who had been captured a few hours earlier in a northern section of the embattled city of Bakhmut, according to a Ukrainian officer with a sidearm on his hip, who was the only other person present. The third, more seriously injured, had been taken to a hospital, the officer said.

The men had injuries that appeared to be battlefield shrapnel wounds. One had his hands tightly bound with green tape; the other was not bound and accepted a cigarette from the officer.

“Do you want to smoke? Water?” the officer asked in Russian after a group of Washington Post journalists entered the ground-floor room with clearance from Ukrainian officials. “They want to interview you.”

Over the next hour in the predawn dark of Monday, after being questioned by Ukrainian intelligence and while they waited for another unit to pick them up for further medical care and administrative processing, the two captives gave a rare detailed account of their experience as Russian ex-convicts recruited by the mercenary group and rushed to the front lines.

As President Vladimir Putin’s raging war on Ukraine has decimated his regular army — with up to 200,000 killed and injured, according to British military intelligence — he has scoured jails and prison colonies for new fighters. Promised pardons in exchange for fighting, convicts make up an estimated 80% of Wagner’s force of 50,000, which has led a fierce months-long assault on Bakhmut.

Mikhail, 35, has a tourniquet on his left leg and his hands taped together on Monday, after being captured during fighting north of the city of Bakhmut in eastern Ukraine. He said he was released from prison in Russia after agreeing to fight in Ukraine with the Wagner mercenary group. (Heidi Levine/for The Washington Post)

Roughly half of the group’s prison recruits have been killed or injured, according to the British estimate. Fewer have been captured.

These two, just hours from the battlefield, were by turns contrite and defensive. They said they believed what they had been told in Russia about “the horrors” being inflicted on Russian-speaking Ukrainian civilians by the Ukrainian military — one of the Kremlin’s main justifications for the war. But they said that they cared more about wiping clean their criminal records with a six-month contract as Wagner fighters, and that getting out of jail was worth the risk of the immediate death penalty Wagner said it would impose if they failed to fight on command.

“I didn’t even have to think about it,” one said of the chance to leave his cell for the battle lines of a country he had never visited.

In interviews, they gave firsthand confirmation of reports of Wagner’s brutal terms of compliance, which they said included being shown videos of Wagner enforcers beating the hands and heads of reluctant fighters with sledgehammers. One of the men said he watched a friend taken off to be shot — or “zeroed” — by a Wagner enforcement team for protesting deployments that sometimes led to hundreds of fighters a day being killed in and around Bakhmut.

The two said the assassination policy had eased in recent weeks as Wagner lost shocking numbers of fighters in combat. The interviews also offered some of the first direct testimony by ex-convicts sent by Russia to fight in Ukraine. One Wagner fighter has sought to defect to Norway, but there have been few firsthand accounts of the group’s recruitment or its battlefield practices.

A Ukrainian official facilitated the interviews in response to a request by Post journalists to speak with surrendered or captured Wagner fighters. There were no preconditions set, and the meeting was consistent with Ukraine’s efforts to document the nature of Russia’s invading forces, including by granting journalists access to prisoner of war detention centers. Unlike those sessions, prearranged by Ukrainian officials in Western Ukraine, this meeting was hastily organized at the front within hours of the men being taken into custody in the combat zone.

The Washington Post was able to independently verify key parts of the two captives’ accounts in Russian public databases, including birth certificates and criminal records of two men with the same first and last names, which were consistent with their stories. Other assertions could not be independently confirmed.

The Post is withholding their last names and not showing their faces in photographs because of the risk of reprisal and to respect the Geneva Conventions, which call for prisoners of war “to be ... protected against insults and public curiosity.”

During the interviews, the armed Ukrainian officer guarding the men remained within earshot in the next room. He occasionally came to interject his own questions for the prisoners or to share information he said they had provided during interrogation. Each man said he was willing of his own accord to answer questions about his experiences.

“Nobody forced me to be here,” one of the men, Mikhail, 35, said of his presence fighting in Ukraine. “I made my own choice.”

For Mikhail and the other captive, Ilya, 30, their transformation — from convicts to combatants, prisoners to prisoners of war — began in the penal colonies where they were serving sentences for alcohol-related deaths.

Captured wounded fighters of Russia’s Wagner mercenary group: Ilya, 30, left, and Mikhail, 35, in the Donetsk region of Ukraine on Monday. Ilya said he was injured by mortar fire and Mikhail said he was hit by a grenade that was launched by a drone. (Heidi Levine/for The Washington Post)

Ilya, 30, a tree cutter with two daughters from the Smolensk Region, said he had been serving six years for “drunk driving” after wrecking his motorcycle while intoxicated and killing his brother, a passenger. Court records in Smolensk confirm that someone with his name was convicted of “driving a motor vehicle while intoxicated ... which negligently caused the death of a person.”

Mikhail, who said he never held a regular job, said he had drunkenly beaten a man to death in a fight in his home near Chita, in Russia’s Far East. Records from Chita regional courts confirm a July 2021 conviction in his name for the “intentional infliction of grievous bodily harm, negligently resulting in the death of the victim.”

He was less than two years into his nine-year sentence last October when inmates known as “goats,” who cooperate with the guards, ushered dozens of convicts into the prison yard of Penal Colony No. 7 in time to see a helicopter descending on the grounds.

Yevgeniy Prigozhin, the founder of the Wagner Group emerged and came to address the assembled crowd. It was shortly after Ukrainian’s autumn counteroffensives had pushed Russian forces from much of Kharkiv and Kherson regions, and the Kremlin was desperate for new fighters.

Prigozhin told the prisoners that he came with President Vladimir Putin’s offer to “wipe the slate clean” of criminal convictions for anyone signing up to fight.

Mikhail also heard Prigozhin promise that anyone who ran away from the front would immediately “go to zero,” the Wagner term for assassinating its own men. Within 10 days, he was on a flight to western Russian, far from his wife and four children in the East, and by November he was in occupied eastern Ukraine.

Ilya arrived in Ukraine a month later, after other Wagner recruiters came to his prison. In addition to erasing his conviction, he expected to be paid more than $1,300 a month as an infantry man, and up to $1,200 more in bonuses for taking out an enemy position or blowing up a vehicle.

Before taking up his Kalashnikov assault rifle, Ilya went through a short stint of infantry training in a stretch of occupied Ukrainian forest with Wagner professionals who had fought in Syria and Africa. Neither he nor Mikhail saw any sign of regular Russian military units in their time fighting with Wagner.

Ilya was one of the fighters responsible for locating Ukrainian troops. But with one drone for his entire unit and no other targeting gear, his only option was to advance under fire until he sighted the enemy with his own eyes. Most days were a slaughter, he said.

On one occasion, more than 400 of his fellow fighters were killed over 72 hours while trying to storm the village of Krasna Hora, he said, with many of the corpses left lying in the snow. Ilya said he ran past several dead men that he recognized.

Mikhail, a captured fighter from Russia’s Wagner mercenary group, with his hands bound with tape on Monday. The Washington Post is not showing the captives’ faces or disclosing their surnames to protect them from reprisal. (Heidi Levine/for The Washington Post)

When some fighters complained, punishment was swift. One of Ilya’s friends from the Smolensk prison, a 24-year-old known by the nickname Kozan, was one of 10 fighters pulled aside after joining in a riot over conditions.

“The written contract could not be violated,” said Ilya, who said he was shown videos of Wagner officers hanging alleged defectors from balconies, breaking their hands or battering them to death. There have been numerous videos, consistent with his description, posted on social media.

“I had thoughts of running away, but they have information about my family, my children,” he said.

Mikhail had similar experiences, being moved frequently to fight around Bakhmut and the Donetsk region that Putin has reportedly pledged to conquer by the spring.

The only significant change, he said, was an apparent loosening of the kill policy that Wagner inflicted on rule breakers as the demands for soldiers continued to soar. Starting just before the New Year, those caught using drugs or alcohol had their contracts extended by several months with no additional pay. Even deserters got a reprieve, Mikhail said.

“Zeroing was canceled,” he said. “Probably because there weren’t enough people.”

Mikhail and Ilya did not fight together but found themselves in the same push to gain ground on Sunday. Mikhail reached a Ukrainian trench and jumped, only see a red flare go off when one of the Russians hit a trip wire.

Within minutes, a drone flew overhead and dropped a grenade. A second explosion knocked him unconscious, and he was picked up by Ukrainians soon after his head cleared.

Ilya said he was caught in a mortar attack after being ordered to storm a tree line concealing Ukrainian fighters. He was hit in the upper rear thigh. Other Wagner fighters fled, he said. Ukrainian soldiers provided first aid after taking him into captivity. Thick bandages covered the wound at the time of the interview.

Prigozhin earlier this month announced on a Telegram messaging channel controlled by his company, Concord, that Wagner was no longer recruiting fighters from Russian prisons, without giving a reason. Ilya said he would advise other convicts not sign up. For one thing, he said he has never been paid.

“I personally did not receive a single ruble from my salary,” he said