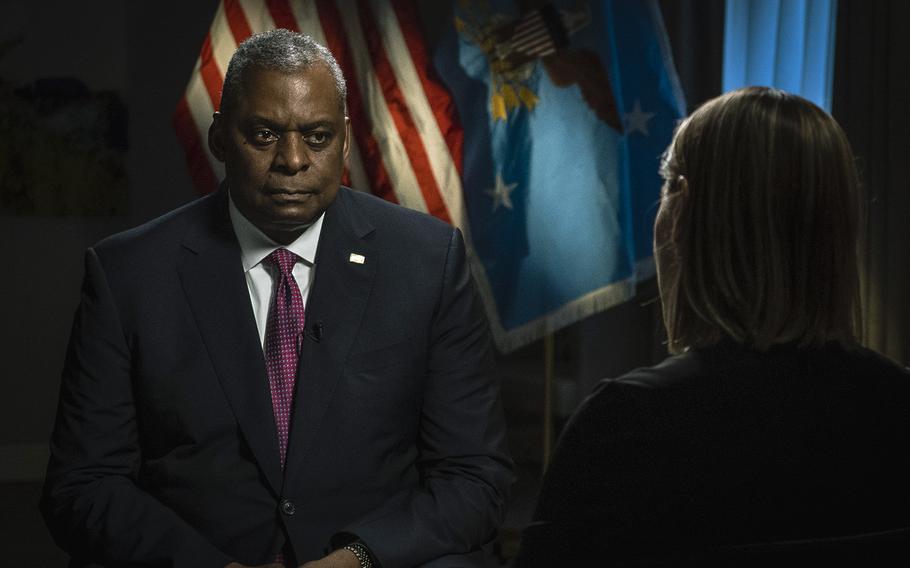

Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III listens to a question during an interview in Brussels, Belgium, on Feb. 15, 2023. (Chad McNeeley/Defense Department)

Western politicians, military leaders and diplomats are convening with one goal at the top of their agenda: Russian defeat. This year's edition of the Munich Security Conference comes almost a year since the Kremlin unleashed its Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine, flaring an open war on the European continent that has claimed tens of thousands of lives, displaced millions, devastated Ukrainian cities and wrought billions of dollars in damage. The war has galvanized the geopolitical West and led to an emboldened and soon-to-be enlarged NATO.

U.S. and European officials are publicly bullish. On Saturday in Munich, Vice President Kamala Harris is expected to give an address that will "convey the continuing U.S. commitment to Ukraine," The Washington Post reported, and assure Kyiv that the vital U.S. support and coordination that has sustained Ukraine's efforts to repulse Russia's invasion will endure. In his speech, French President Emmanuel Macron plans to discuss how to "ensure Russian defeat" and how the West can bolster Kyiv in the months to come.

At meetings this week with NATO defense ministers in Brussels, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said a possible Ukrainian spring counteroffensive has "a real good chance of making a pretty significant difference on the battlefield and establishing the initiative." On the sidelines of the same session, Gen. Mark A. Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs, declared that an impoverished, isolated Russia had already failed.

"Russia is now a global pariah and the world remains inspired by Ukrainian bravery and resilience," Milley said. "In short, Russia has lost; they've lost strategically, operationally and tactically."

There's no doubt that the war waged by Russian President Vladimir Putin has been a disaster for his country. Estimates of Russian casualties on the battlefields in just the space of a year range as high as 200,000. A mass mobilization of some 300,000 troops appears to have been more or less fully deployed to Ukraine's battlefields and, at best, may have only blunted some Ukrainian advances to reclaim territory lost to Russia. In recent weeks, the Kremlin's losses may have been particularly acute and demoralizing.

A rumored new Russian offensive may prove even bloodier. "If current casualty rates are any indication, the coming attack could result in unprecedented loss of life and spark a complete collapse in morale among Russia's already demoralized mobilized troops," noted Peter Dickinson of the Atlantic Council. "This would make life very difficult for the Russian army in Ukraine, which would find itself confronted by a breakdown in discipline that would severely limit its ability to stage offensive operations."

Moreover, the Russian military has seen its arsenal severely depleted. It has lost nearly half its main battle tanks, according to an estimate published this week by the International Institute for Strategic Studies, and is dipping into inventories of older-era (and sometimes Soviet) weaponry. Russia's ammunition stockpile is rapidly dwindling (though Ukraine's is, too).

The war and popular mobilization triggered an astonishing exodus of people - perhaps as high as nearly a million emigres - desperate to leave Russia. Activists and independent journalists left, but so, too, did 10 percent of the nation's IT workforce. "This exodus is a terrible blow for Russia," Tamara Eidelman, a Russian historian who moved to Portugal after the invasion, said to my colleagues. "The layer that could have changed something in the country has now been washed away."

Western sanctions on Russia have contracted its economy, impacted the country's industrial capacity in some sectors, and brought an era of Russian integration into Europe to a shuttering halt. But while the measures have exacted a painful toll on Russia, they have not forced Putin to reconsider his war of neo-imperialist revanchism.

"Instead of growth, we have a decline. But saying all of that, it's definitely not a collapse, it's not a disaster," Sergey Aleksashenko, former first deputy chairman of Russia's central bank, said at a panel discussion in Washington last month. "We may not say that the Russian economy is in tatters, that it is destroyed, that Putin lacks funds to continue his war. No, it's not true."

Part of the reason for that is the significant amount of revenue still generated by European imports of Russian gas and oil. No matter their avowed desire to wean themselves off Russian energy dependence, most European countries could not go cold turkey on Russian energy even as Putin's war machine pummeled Ukraine. But the new geopolitical fault lines created by the invasion may accelerate Europe's transition to decarbonized economies and further diminish Russia's leverage over the continent.

"The results already speak for themselves; for the first time ever last year, wind and solar combined for a higher share of electrical generation in Europe than oil and gas," wrote Brent Peabody in Foreign Policy. "And this says nothing of other decarbonization efforts such as subsidies for heat pumps in the EU, incentives for clean energy in the United States, and higher electric vehicle uptake everywhere."

For all the certainty of Russian failure, the war still looks nowhere close to ending. Analysts put this down in part to the personal determination - and delusions - of the Russian leader himself.

"Since February 2022, the world has learned that Putin wants to create a new version of the Russian empire based on his Soviet-era preoccupations and his interpretations of history," wrote Fiona Hill and Angela Stent in Foreign Affairs. "The launching of the invasion itself has shown that his views of past events can provoke him to cause massive human suffering. It has become clear that there is little other states and actors can do to deter Putin from prosecuting a war if he is determined to do so and that the Russian president will adapt old narratives as well as adopt new ones to suit his purposes."

They cite a former Finnish diplomat who thinks fondly of the days of the Soviet Politburo, since, in Putin's Russia, there appears to be "no political organization in Russia that has the power to hold the president and commander in chief accountable."

In the face of an opaque, implacable adversary, strategists in Washington are keen to avoid a prolonged war. Milley himself gestured to the need for realism on both sides of the conflict. "It will be almost impossible for the Russians to achieve their political objectives by military means. It is unlikely that Russia is going to overrun Ukraine. It's just not going to happen," he told the Financial Times. "It is also very, very difficult for Ukraine this year to kick the Russians out of every inch of Russian-occupied Ukraine. It's not to say that it can't happen . . . But it's extraordinarily difficult. And it would require essentially the collapse of the Russian military."

As The Post reported earlier this week, while the Biden administration is adamant about its continued support to Kyiv, it is also making clear to Ukrainian authorities that the current level of security and economic assistance may be difficult to sustain, especially with the current Republican-led House. "We will continue to try to impress upon them that we can't do anything and everything forever," one senior administration official told The Post, referring to Ukraine's leaders.