Guards at U.S. Army Regional Correctional Facility-Europe practice a maneuver used to remove noncompliant inmates from their cells Tuesday, Nov. 22, 2022. (Phillip Walter Wellman/Stars and Stripes)

SEMBACH KASERNE, Germany — Forest and farmland surround this small American military base, which is home to some of the least popular temporary accommodations in southwest Germany.

For nearly a decade, U.S. service members accused or convicted of crimes in Europe and Africa have been brought to a jail that many Germans and Americans living in the area know little about.

“Some people on Sembach don’t even know we’re here,” said Army chaplain Capt. Jeremi Wodecki, who has worked at U.S. Army Regional Correction Facility-Europe for almost two years. “But we’re a very busy facility and we make a huge impact across the armed forces.”

Despite its name, the facility is also used by the Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps and is the only military jail for the Europe and African theaters. It’s where U.S. service members stationed as far away as Italy, Turkey and Djibouti are taken to be confined.

Stars and Stripes was recently granted access to the site to observe daily operations.

Security fencing surrounds U.S. Army Regional Correctional Facility-Europe at Sembach Kaserne, Germany. (Phillip Walter Wellman/Stars and Stripes)

A dozen inmates were being held at the time of the late November visit, about a third of the jail’s capacity. While the number may seem small, officials say it’s deceiving because of the high occupant turnover.

One of the jail’s primary functions is to hold inmates en route to larger, branch-specific prisons in the United States. Those not bound for the U.S. are awaiting courts-martial or serving sentences of less than a year.

While most inmates are active-duty service members, Defense Department civilian employees also can be detained at the facility under certain circumstances.

The short stays mean more people arrive and get released at any hour of any day, including weekends and holidays, and that guards always must be prepared.

“It really is a 24-hour-a-day, 7-day-a-week service we provide,” said Army Master Sgt. Marcus Mitchell, who supervises the guards.

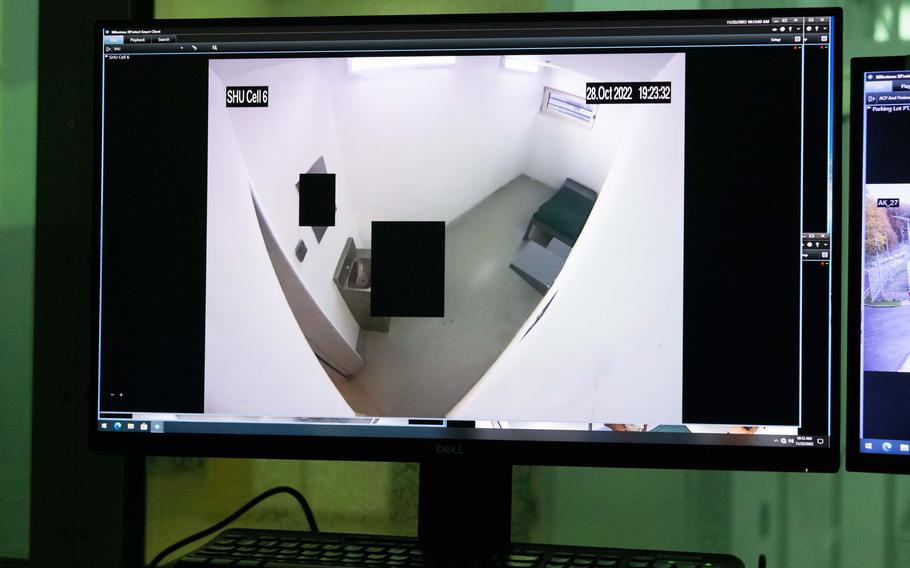

A computer in U.S. Army Regional Correctional Facility-Europes control room shows surveillance footage of a special housing unit cell, with blacked-out areas that are programmed in to provide privacy when inmates use the toilet. (Phillip Walter Wellman/Stars and Stripes)

Upon arrival, inmates are reminded that military rules and discipline are enforced and that staff members are to be addressed by their rank.

Staffers, meanwhile, must learn to engage with inmates of all seniority levels equally.

“Everyone is treated the same once they come through these doors: as a prisoner,” Mitchell said. “As far as their rank, they kind of lose it because they are here, and they are confined.”

A central control room allows guards to observe all areas holding inmates.

Three communal bays with bunkbeds house most occupants. A row of individual cells, each a few yards long and only about an arm’s length wide, equipped with a bed, toilet and sink, is where those segregated for disruptive behavior at the facility are kept.

Guards practice removal of an unruly prisoner from a cell Tuesday, Nov. 22, 2022, at the U.S. military's jail in Sembach, Germany. (Phillip Walter Wellman/Stars and Stripes)

Cameras monitoring the cells are programmed with blacked out areas that cover inmates’ private parts when they use the toilet. This feature, which didn’t exist a few years ago, is pretty much the only privacy afforded to the inmates.

Staffers say the cameras are vital to detecting self-harm and unruly behavior. When things get out of hand with an inmate, a procedure known as a forced cell extraction may be required.

Five guards remove the inmate from his cell, search him and return him when the go-ahead is given. This has happened a few times in recent months, staffers said.

However, most inmates behave well and focus on rehabilitation, which includes counseling, services for substance abuse and vocational activities, they added. Stars and Stripes was prohibited from speaking with any inmates while at the facility.

Army chaplain Capt. Jeremi Wodecki said he provides equal support to inmates and prison staff at U.S. Army Regional Correctional Facility-Europe. Wodecki spoke about his experiences at the facility on Nov. 22, 2022. (Phillip Walter Wellman/Stars and Stripes)

Wodecki, the chaplain who specializes in teaching inmates how to cope with stress, said he’s had to provide just as much support to guards, who often work 12-hour shifts in groups of six or seven.

“Here, you have to serve two groups of people,” Wodecki said. “It’s a tough job for the guards. They are far away from home. Many of them are single and have to work long hours, even on the weekends. It’s stressful for them.”

Watch commander Sgt. James Stanphill, who’s been at the jail for nearly two years after stints at Guantanamo Bay and the U.S. Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth, Kan., agrees that the work can be difficult but said he’s experienced what he calls “squad integrity” since assuming the role.

The facility recently received the Brig. Gen. Thomas F. Barr Award, which recognizes the best detachment-sized correctional unit with U.S. Army Corrections Command.

“Through our work, we have proven that you don’t have to be the biggest unit to be the best,” Stanphill said.

The Sembach jail is a level-one correction facility, the lowest level of security in the military’s three-tier prison system. The Defense Department has one other level-one facility abroad, in South Korea.

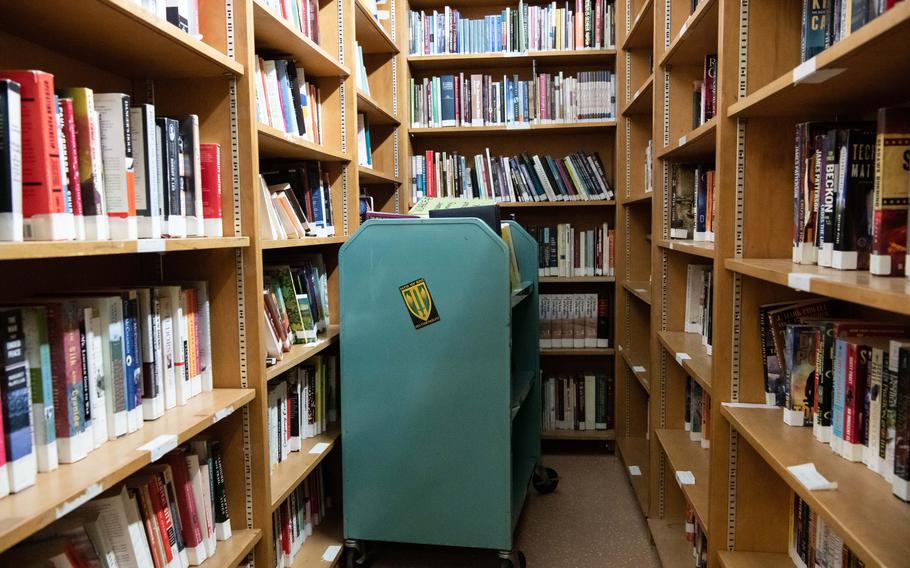

Resources at U.S. Army Regional Correctional Facility-Europe in Sembach, Germany, are limited, but inmates have access to over 4,000 books and movies. The facility can hold detainees for up to a year. (Phillip Walter Wellman/Stars and Stripes)

In addition to the guards, a few dozen other troops make up the jail’s small, multi-branch staff. Among the other staff members are medics, behavioral health specialists and non-Army liaisons, who focus on transporting their branch prisoners to the U.S.

Since it opened in 2014, no one has tried to break out of the facility.

But the fact that inmates are routinely transported to and from the jail increases the chance of an escape attempt, said facility commander Army Maj. Randall Zamora.

“That’s the one thing that keeps me up at night,” Zamora said.

And finding an escapee off base could be challenging because there is minimal cooperation between the jail and German authorities, he said.

But both sides have made overtures to change that, with the goal of conducting a full-scale exercise with jail staff and German police sometime next year.

“It’s important we establish these relationships and are able to build on them because this is a real-world operation,” Zamora said. “We have to try to expect the unexpected.”

The special housing unit is an area of U.S. Army Regional Correctional Facility-Europe that consists of several individual cells for inmates who must be kept apart from others. (Phillip Walter Wellman/Stars and Stripes)