Wojtek Bauman, a volunteer for the Polish charity Be a Hero UA, loads extra off-road tires into a vehicle bound for war-ravaged eastern provinces in Ukraine, at a warehouse on the outskirts of Warsaw, Poland on Nov. 4, 2022. (J.P. Lawrence/Stars and Stripes)

WARSAW — Every Friday at about midnight, a warehouse parking lot on the outskirts of Poland’s capital becomes the starting point for a convoy of supplies bound for Ukraine.

Volunteers with Be A Hero UA, a Polish charity organization, pack Jeeps and other SUVs earmarked for the front lines with essentials for civilians and soldiers: food, clothes, first-aid kits, tires, generators and, at the recent request of one U.S. veteran fighting in Ukraine, charging stations for the Starlink satellite internet system.

“For me, it’s not just about supporting Ukraine, I’m supporting people who stand up and fight. They have names,” said Marta Małecka, the nonprofit’s co-founder.

One of them is Issac Olvera, a former U.S. Marine Corps infantry major who joined Ukraine’s legion of foreign fighters in March and is now advising the country’s armed forces. He had asked for charging stations to help the men with whom he was fighting maintain long-range communications as they went on missions.

A steady stream of Western aid led by the United States has kept the Ukrainian military outfitted with heavy weapons and other munitions since Russia’s invasion in February. But gaps remain on the more granular level, where individual soldiers and units must turn to private donations for unmet needs.

Requests for drones, vehicles, generators, body armor and other equipment flow incessantly, at all hours of day and night, to a network of volunteers around the globe.

Marta Malecka, a businesswoman from Warsaw, Poland, pulls a load of clothing for Ukrainian children on a pallet jack in a warehouse on the outskirts of Warsaw, Poland, on Nov. 4, 2022. Malecka is co-founder of Be a Hero UA, a charity that sends humanitarian aid across the Polish border to regions of Ukraine ravaged by war. (J.P. Lawrence/Stars and Stripes)

Małecka fills the requests from Warsaw. Another Pole, Joanna Wylegała, facilitates deliveries from Poznań, home to the first permanent U.S. military base on NATO’s eastern flank. And there is “War Santa,” a moniker used by a 36-year-old former U.S. Air Force sergeant to hide his name for security reasons. He answers the calls for help from his home in Texas.

War Santa works anonymously to funnel specialty gear to Ukrainian soldiers, Americans and other foreign fighters, using his military intelligence background to procure equipment and either hand-deliver or ship it. Poles offer vital assistance in getting certain military supplies, which might skirt customs regulations, through the Polish-Ukrainian border.

“What I take in isn’t necessarily humanitarian; it is to help out the warfighter and help them do their job as if they were properly outfitted in the U.S. military,” War Santa said. “The U.S. government and Poland and Ukraine give soldiers specialty equipment on top of the basic gear, but there’s a lot of stuff that they don’t get so that’s where we’re going to meet those needs.”

Since March, War Santa has provided nearly $130,000 in high-end drones, night-vision devices, encrypted radios, cold-weather clothes, helmets, uniforms, body armor and other supplies to special forces units, demining teams, artillery units and members of Ukraine’s main intelligence agency and 92nd Mechanized Brigade.

War Santa started the equipment runs to assist a friend fighting in the Georgian Legion, a group of foreign volunteers formed by ethnic Georgians, and expanded his reach as word of his deliveries spread. No one besides his boss at an investment bank — a fellow veteran — and a few other people know about the War Santa persona and his side gig, and he wants to keep it that way.

“I don’t do it for the fanfare,” he said. “It’s the right, human thing to do.”

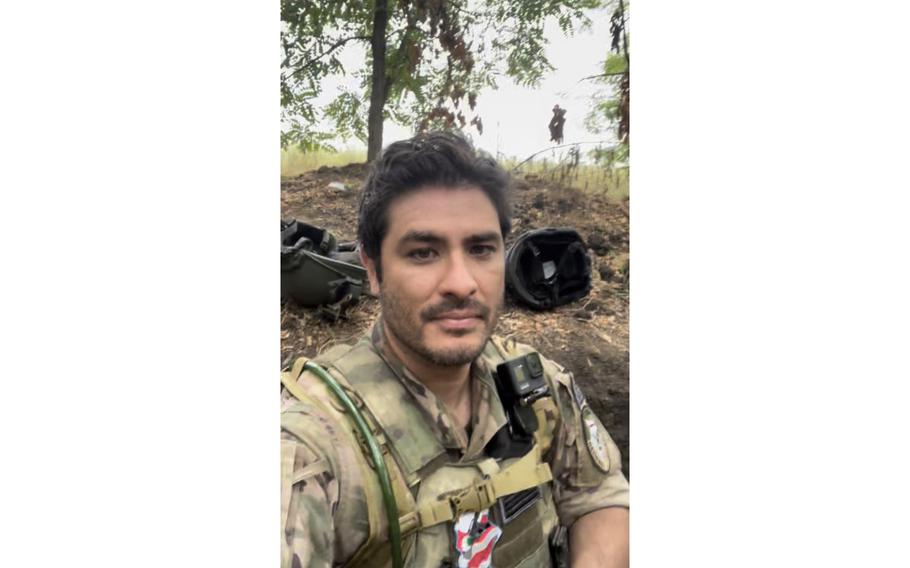

War Santa, a 36-year-old former U.S. Air Force sergeant, photographed in the trenches in Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine. He works anonymously from his home in Texas to funnel specialty gear to Ukrainian soldiers, Americans and other foreign fighters. (War Santa)

Fundraising pays for much of the donated gear, but War Santa and Olvera also have contributed tens of thousands of dollars to the effort. They said they fill a unique niche: obtaining pricey, sophisticated equipment for units that don’t have enough of it to go around.

“Coming to Ukraine, especially coming from the U.S. — a very well-funded military — one of the biggest shocks was the shortage of equipment,” said Olvera, a veteran of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. “I think this is money well spent. In the grand scheme of things, when I’m 80 years old, it won’t matter that I spent $30,000 or $50,000 to help save the country.”

Olvera, 41, said he quit his job in management consulting and left Texas to fight for Ukraine out of moral and patriotic duty. He said he felt compelled to defend the cornerstones of Western democracies: rule of law, free and fair elections, freedom of speech and freedom of assembly.

“I thought it was unfair for Ukraine to fight for these values alone,” he said.

Mamuka Mamulashvili, commander of the Georgian Legion, said his 1,300 troops lack thermal-vision and night-vision goggles for night battles and driving in front-line zones in the dark. Soldiers in the unit, created in the aftermath of Russia’s incursion into Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region in 2014, obtain much of their own equipment using Twitter and rely heavily on private donations through nonprofit organizations.

“We have no luxury to get equipment from [the Ukraine] Ministry of Defense because the Ministry of Defense has no equipment itself,” Mamulashvili said. “We’re trying to do it ourselves and concentrate as many useful items for the guys as we can.”

The most critical supplies for the war are drones for reconnaissance, night-vision goggles to spot ever-present enemy drones, secure communication radios, vehicles and, as winter approaches, high-quality cold-weather gear, according to fighters and volunteer equipment suppliers.

Getting them into Ukraine can be tricky and dangerous. Time-consuming paperwork is needed for sensitive items such as drones, and transporting certain equipment — firearm magazines, hard-body armor — can violate export control laws set by the U.S. State Department’s International Traffic in Arms Regulations.

Volunteers do their best to stick to official rules and regulations, but the urgency of their cause sometimes requires creative alternatives. Drones, scopes, thermal-vision goggles and other sensitive items have crossed borders in bundles of clothes or, more often, buried in pet food because “it smells, so no one checks,” said one Pole.

Kathy Stickel, a 53-year-old former corporal in the U.S. Army Reserve, doesn’t hide the drones that she ferries from Poland into Ukraine, but she doesn’t leave them in plain sight either. She said she came to Ukraine from California at the start of the war with a nagging need from her Mormon childhood to help Jews. Stickel fixated on Odesa, a historically Jewish city on Ukraine’s southern coast where she largely bases her operations.

She evacuated civilians and delivered humanitarian aid for months before switching her focus to supporting soldiers.

“The best thing we can do for the Ukrainians is to stop them from being killed by the Russians,” she said.

Stickel is convinced a surveillance drone could have saved the life of her friend, Dane Partridge, a 34-year-old U.S. Army veteran who died last month in a Russian ambush in the Zaporizhzhia region in southeastern Ukraine. His unit in Ukraine’s foreign fighter legion had asked for more drones. Stickel raised money for them on Twitter, ordered them from Wylegała in Poznań and delivered them to Partridge’s men shortly before his funeral.

She worked as fast as possible.

“I believe in the trampoline method — nothing should stay longer than a day and a half in any warehouse,” Stickel said.

War Santa distributes his gear with similar speed. Once he flies into Warsaw, he races to Lviv in western Ukraine, where he makes his first deliveries, and then on to Kyiv, Ukraine’s capital. He hands over equipment in bars, train stations, malls, strangers’ apartments and even the front lines. Olvera covers deliveries to places War Santa doesn’t have time to reach.

During the summer, War Santa started taking a train to Zaporizhzhia and spending time in the trenches. The experience left him feeling like a “sitting duck” but allowed him to see some of the supplies that he provided in action.

Some of the gear that War Santa has carried into Ukraine through Poland. He estimates he has outfitted at least 12 units with nearly $130,000 worth of equipment. (War Santa)

He travels with 300 to 400 pounds of equipment packed in four deployment bags, sometimes sleeping on them on overnight trains to Kyiv to protect their costly contents. Most airlines, after learning about his mission, waive his bag fees, and foreign government officials have helped clear legal roadblocks knowing he is not a profiteer, War Santa said.

“They say, ‘No, I’m not telling you to do this but keep [expletive] doing it,’ ” he said.

War Santa has spent 42 days out of the country making equipment runs and dedicates about 20 hours per week to fielding requests. The work is grueling, but he said he draws strength from his War Santa alter ego — “when you put this different mindset on, you can go and do everything” — and the poignant scenes that he witnessed of Ukrainian men in uniform saying goodbye to their wives and children in train stations at the start of the war.

“Those families just stick in my head,” he said. “Whenever I’m frustrated because of how expensive things are, or not getting enough donations or I can’t get the gear sometimes on time because the need is so great, I just remind myself this is what it’s about. This is genocide going on over there, and we have to keep going.”

Małecka, the leader of the Polish Be A Hero UA nonprofit, said volunteers not only form a vast network of knowledge and connections to tap into but lean on each other for emotional support as well. On a recent Friday night, she paused loading supplies into a car to hug Jagoda Pasko, a Polish volunteer who had just returned from deliveries at the front lines.

Wylegała, a frequent contributor along War Santa’s logistical route, said volunteers work tirelessly to help one another, united in their pursuit to outfit soldiers for the increasingly cold and punishing battlefield.

“We have the same goal," she said. "Victory for Ukraine and to finish this war."