Europe

Meloni sworn in as Italy's first female prime minister

The Washington Post October 22, 2022

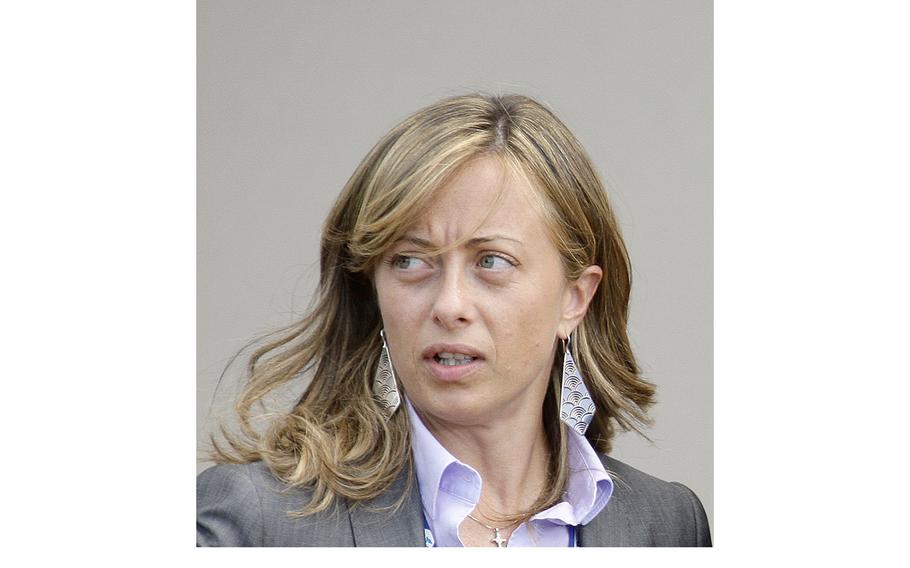

Giorgia Meloni, seen here attending a summit in L’Aquila, Italy on July 9, 2009, was sworn in as Italy’s first female prime minister on Saturday, Oct. 22, 2022. hold that office. (Stefano Rellandini, Pool)

ROME - Giorgia Meloni completed her groundbreaking rise in Italian politics Saturday, when she was sworn in as the country's first female prime minister, giving her once-fringe party a level of power that has been out of reach for other far-right forces in Western Europe.

The ceremony took place at Italy's presidential palace. Her cabinet is expected to be approved in a parliamentary confidence vote early next week.

Meloni's ascent could be a transformative moment in a country that has sometimes been a test lab for broader political shifts, whether with fascism a century ago or, more recently, the personality-driven theater of Silvio Berlusconi. Now, Italy will be led by Meloni, who has honed a distinctive brand of far-right politics - acting as a liberal-baiting firebrand on social issues, while pitching herself as a steady, establishment-style hand on foreign policy and spending.

But if such a mold has any chance of catching on in Europe, Meloni needs to succeed in the job.

It won't be easy.

She faces an economy that has defied years of rescue attempts and was in bad shape even before soaring inflation and energy costs. There is plenty of skepticism from fellow leaders across the continent, who worry that her Italy-first vision will lead to fights in Brussels. And she is already grappling with challenges from the other parties in her coalition, which so far have produced only headaches and controversies.

Female leaders are not new in Europe, but they are downright revolutionary in Italy, where the constellation of parties are led almost entirely by men. Meloni, 45, can be loud and caustic and quick with a verbal dagger when she feels insulted. Her party gained popularity steadily over the last five years despite its connection to earlier post-fascist parties - a result that some pundits say could only happen because Meloni represented such a break from the familiar brand of politics.

"We started from zero," said Marco Marsilio, the governor of Abruzzo, a fellow member of the Fratelli d'Italia party who has known Meloni since she was a teenager.

When the far-right coalition swept to victory last month, it made Meloni's ascent to prime minister nearly inevitable. Her party won 26 percent of the overall vote, more than any other party. But her grip on power is nonetheless fragile. Italian voters are renowned for throwing their support behind leaders and then swiftly ditching them.

The last several Italian governments have been brought down by infighting. And this time, the sparring started even before the government was sworn in.

Much of the turmoil has been sparked by Berlusconi, the 86-year-old billionaire tycoon and four-time prime minister who heads Forza Italia, a junior party in the ruling group.

First, last week, cameramen caught sight of a note written by Berlusconi offering a critique of Meloni's personality. "Overbearing, arrogant," he'd written.

Then several audio leaks showed Berlusconi boasting about a recent birthday gift from Russian President Vladimir Putin, who'd sent him 20 bottles of vodka and a "very kind letter," which Berlusconi said he had responded to with an "equally sweet letter" and a pack of Lambrusco wine. The leaks also showed Berlusconi offering a Kremlin-friendly narrative of the war in Ukraine, saying that Putin had reluctantly launched the "special operation" in response to popular will, with the hope of installing "more sensible leaders" in Kyiv.

Meloni responded with an ultimatum: Anybody who doesn't agree with Italy's Atlantic and European principles "will not be able to be part of the government, at the cost of not forming a government."

Berlusconi's comments about Russia amount to an additional challenge, because they counter Meloni's vision of a government that forcefully backs Ukraine and NATO.

Berlusconi had pitched himself as an elder statesman in the coalition. His own party, though diminished in popularity, was generally seen as more centrist than its partners, which include Meloni's Fratelli d'Italia and the League party, led by Matteo Salvini.

But Berlusconi is having trouble ceding ground.

Meloni once served under him as a youth minister; now she leads a party with three times more support than his own. Some critics, noting Berlusconi's infamous Bunga Bunga parties, his demeaning portrayal of women on TV, and his habit of commenting on female beauty, say he doesn't know how to handle a personality like Meloni, who outmaneuvers him on social media.

After Berlusconi's list of adjectives for Meloni became public, she said he'd left one off the list.

"An adjective is missing: I am not blackmail-able," she said, an apparent reference to an earlier maneuver, when Berlusconi's party didn't support a Fratelli d'Italia candidate for head of the Senate. The candidate, Ignazio La Russa, known as a collector of fascist memorabilia, won anyway.

The leaked audio, reported by LaPresse, provided a reminder of the Russian sympathies that have always lurked in Meloni's coalition. Although Meloni has shown no affinity for Putin, Salvini has questioned the efficacy of Russian sanctions and once wore a Putin T-shirt while touring Red Square.

Berlusconi, meanwhile, has long had a Trumpian soft spot for strongmen. He's hosted Putin at his Sardinian villa, and in 2015 he became one of the rare Western politicians to visit recently annexed Crimea, where he called Putin the world's "number one" leader.

Enrico Letta, the leader of Italy's center-left Democratic Party, said on Twitter that Italy is "undergoing a dangerous shift," becoming more ambiguous in its stance on Russia and Ukraine. One of the biggest parties that will be in opposition, the Five Star Movement, has pushed for months to end arms shipments to Ukraine.

Though Berlusconi's apparent unreliability won't make life easy for Meloni, the dynamic is so far playing to her personal advantage. Mykhailo Podolyak, an adviser to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, said Thursday that while Berlusconi is "under the influence of vodka," Meloni was demonstrating "true principles."

Meloni had said that "with us in government, Italy will never be the weak link of the West."

Ferruccio de Bortoli, the former editor in chief of the Corriere della Sera newspaper, said Meloni has come away looking "even more pro-West, even more pro-NATO, than she looked before."

"I think Berlusconi's variety show politics ended up representing a small but meaningful advantage for Giorgia Meloni's leadership," he said.

Friday morning, Meloni spoke to news organizations, flanked by Salvini and Berlusconi after they had consulted with Italian President Sergio Mattarella on the formation of a new government. Meloni said they had agreed on the need to make things official "in the shortest possible amount of time."

She said the support behind her was "unanimous."

Berlusconi, at that moment, looked toward Salvini and raised his eyebrows.