Europe

WHO weighs declaring monkeypox a global emergency as European cases surge

The Washington Post June 24, 2022

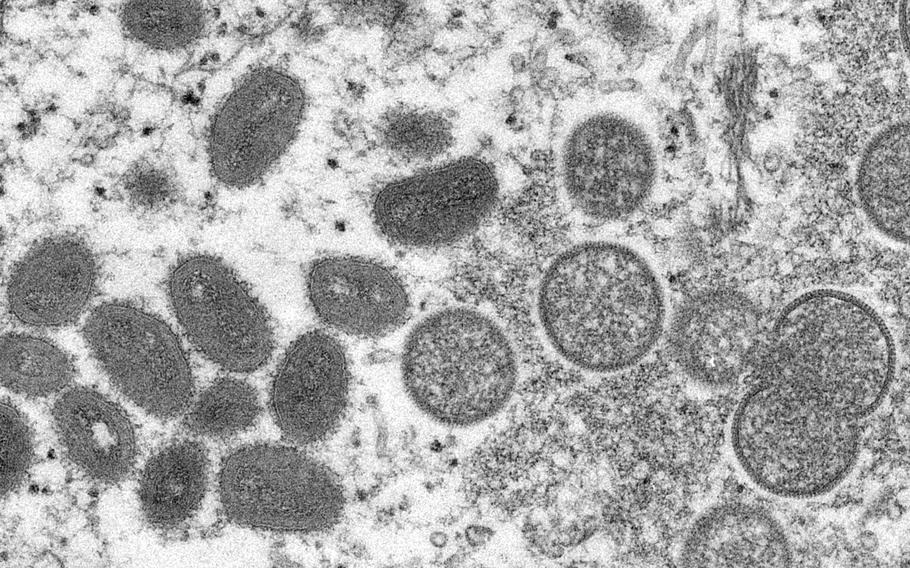

This 2003 electron microscope image shows mature, oval-shaped monkeypox virions, left, and spherical immature virions, right, obtained from a sample of human skin associated with the 2003 prairie dog outbreak. (Cynthia S. Goldsmith, Russell Regner/CDC)

LONDON — The World Health Organization is weighing whether to declare monkeypox an international emergency — a decision that could come as early as Friday. A declaration could escalate the global response as cases rapidly rise in Britain despite efforts to contain it.

Britain, where almost 800 cases of the virus have been recorded in the past month, has the highest reported number of infections outside of Central and West Africa — and case trends here are worrying experts throughout Europe, the epicenter of the outbreak, who are weighing the best approach in the midst of the years-long coronavirus pandemic.

Monkeypox cases rose almost 40% in Britain in under five days, according to data shared by the U.K. Health Security Agency. As of June 16, 574 cases had been recorded, and by June 20, the number had risen to 793.

After Britain, Spain, Germany and Portugal have the most recorded cases. And it’s a growing threat outside of Europe: More than 3,200 cases have been confirmed across 48 nations in the past six weeks, according to the WHO, which publishes data on monkeypox in weekly intervals. As of June 15, one death had been reported.

The WHO’s International Health Regulations Emergency Committee met Thursday to discuss whether the monkeypox outbreak should be labeled a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern,” which would mobilize new funding and spur governments into action. The novel coronavirus, which causes covid-19, was labeled a PHEIC following a similar meeting in January 2020.

So far, the response in most European countries has been to focus on outreach to at-risk communities, contact tracing and isolation for known monkeypox cases. That may change if the WHO, which first sounded the alarm about monkeypox infections in countries where the virus is not endemic in May, increases the threat level of the outbreak.

“The emergency committee and then the [WHO] director general’s announcement will raise the political level of this,” David Heymann, a professor of infectious-disease epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine who attended the meeting as an adviser, told The Washington Post.

Monkeypox is spread through close contact and has so far primarily affected men who have sex with men. It begins with flu-like symptoms before fluid-filled lumps or lesions appear on the skin, which can leave behind permanent scarring. Health officials say that the latest outbreak has frequently brought genital rashes, and while most cases are mild and patients recover in three weeks, the virus can be fatal and is more of a risk to pregnant people or those with weakened immune systems.

To contain the outbreak, a broader understanding of its origins along with vaccination of at-risk groups and contact tracing is imperative, experts say, although they note some patients may not want to divulge information about who they have been intimate with - which can complicate the public health response.

“One of the difficulties people are having with implementing control is actually getting a full list of people’s sexual contacts,” said Paul Hunter, a professor of medicine at the University of East Anglia. “It’s exactly the issue that we faced when we were dealing with HIV/AIDS in the early [1990s].”

And, as in the early days of the coronavirus outbreak, it’s unclear whether cases in some countries are going undetected. Some experts speculate that Britain may have higher numbers because its extensive public health surveillance network allows it to identify more infections.

WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus acknowledged at the start of Thursday’s meeting that monkeypox is likely more widespread than official numbers indicate. “Person-to-person transmission is ongoing and is likely underestimated,” he told members of the emergency committee.

The United Kingdom has proactively tracked people with known cases of monkeypox and in some cases, distributed smallpox vaccines, which are known to protect against monkeypox infection, to their close contacts and at-risk groups. In theory, this approach — which Hunter described as “ring vaccination” — “should have worked,” he said.

But as infections have surged and authorities have struggled to “track down the contacts of cases early enough to make an impact,” Hunter said he has grown “less confident.”

“Unless we turn a corner very soon on this, I think we will probably need to start thinking about what’s next,” he added.

British health officials said Tuesday that some gay and bisexual men, who are considered to be at higher risk of exposure, will be offered vaccines to help curb the monkeypox outbreak. The U.K. Health Security Agency stressed that although the virus is more of a threat “in the sexual networks of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men,” anybody can contract the illness through close contact with an infected individual.

Scientists are studying this outbreak and will know more once the virus is sequenced. “We’re beginning to understand how widespread [monkeypox] really is,” Heymann said. “We know it’s widespread in certain populations, and we need to know whether it’s spreading in other populations as well.”

Two years after he treated Germany’s first coronavirus patient, Clemens Wendtner treated Germany’s first monkeypox patient in May. The man, who has not been identified, was a sex worker from Brazil, said Wendtner, chief physician of infectious diseases at Munich’s Schwabing clinic.

A handful more monkeypox patients have been treated on his ward in recent weeks, Wendtner said. Some have reported “very painful” rectal lesions, for which intravenous painkillers are given to help with the discomfort. Wendtner and his colleagues have been closely recording their discoveries amid this outbreak, documenting recently their discovery of monkeypox virus DNA in both semen and blood.

Most patients were discharged after a day or so and advised to isolate for 21 days at home - in line with Germany’s infectious-disease law. The majority of cases have been reported in Berlin, one of Europe’s party hot spots, which is set to host Pride events next month.

“Summer season is party season,” he warned, adding that more cases in the coming week are likely and that the current outbreak may not have peaked yet.

While men are significantly more at risk, Wendtner warned that female sex workers could also be in danger. “The risk factor is a pattern of sex without protection,” he explained.

Outside of Europe, other countries are also grappling with new cases.

The first case of monkeypox in the United States was detected on May 17. Over the past five weeks, more than 100 cases have been added, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. California, New York and Illinois are listed as the states with the highest level of infection.

Some experts in the United States are calling on the White House to implement thorough testing to avoid the failures of the coronavirus pandemic.

Singapore confirmed a case of monkeypox in a British man on Tuesday, the first in Southeast Asia. South Korea on Wednesday also confirmed its first case of monkeypox. The patient is a South Korean national who entered the country from Germany, health officials said. On Thursday, South Africa also announced its first case of monkeypox, Reuters reported. The 30-year-old has no travel history, health experts said, meaning his illness would not have been contracted outside of South Africa.

It’s important to remember, experts say, that this is not a new disease. Monkeypox has been circulating in Africa for decades - leading some to point out a double-standard in the response to the outbreak in Europe.

“This is a disease which has been neglected,” Heymann said. After smallpox was eradicated in 1980, the world stopped administering smallpox vaccines as a matter of routine. Monkeypox, which is less contagious than smallpox, continued to spread in West and Central Africa, but outbreaks there were not thoroughly investigated due to lack of resources, he added.

The WHO’s Tedros said Thursday that nearly 1,500 suspected cases of monkeypox, and some 70 deaths, have been reported in central Africa this year. “While the epidemiology and viral clade in these cases may be different, it is a situation that cannot be ignored,” he warned.