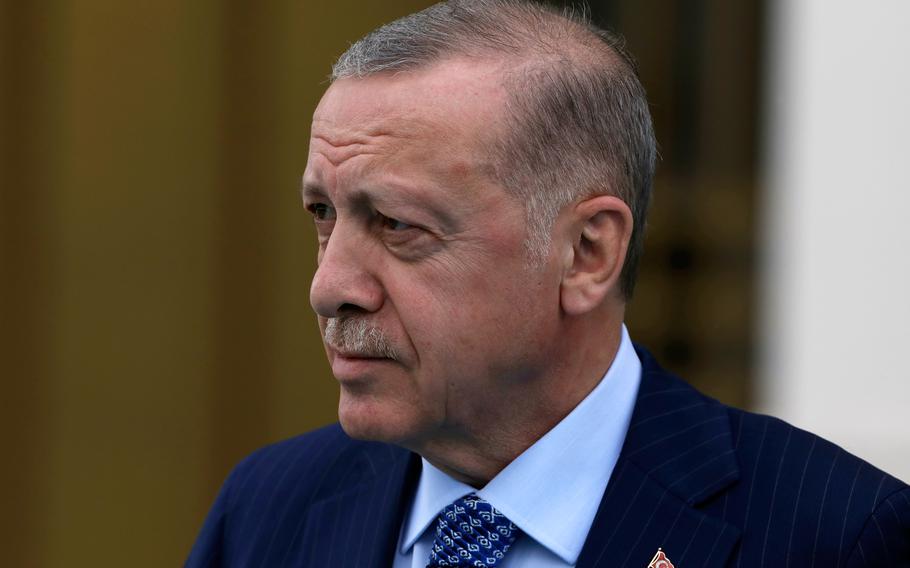

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan arrives for a welcoming ceremony for his Algerian counterpart, Abdelmadjid Tebboune, in Ankara, Turkey, Monday, May 16, 2022. (Burhan Ozbilici/AP)

At the heart of Turkey’s threat to stop NATO’s Nordic expansion is a clash of viewpoints over Kurdish political groups.

Sweden, which along with Finland is seeking entry into the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, has been one of Europe’s most willing recipients of migrants fleeing conflict, including Kurds. Turkey opposes Kurdish demands for statehood and its president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has called Sweden a “nesting ground for terrorist organizations.” Since NATO admits new members only by unanimous consent, his views can’t easily be ignored.

1. Why do the Kurds matter to Turkey?

The Kurds are an Indo-European people, about 30 million strong, and the world’s largest ethnic group without a state of its own. Their homeland is divided among Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran. The Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, has fought Turkish forces on and off since the mid-1980s as it seeks an autonomous region for Kurds inside Turkey. Turkey is particularly focused on the People’s Protection Units, or YPG, a Kurdish militia in Syria that was instrumental in the defeat of the Islamic State there. Turkey views the YPG as a security threat due to its ties to separatist Kurds in Turkey.

2. What’s Sweden’s policy on the Kurds?

Sweden has long sought to promote human rights and respect for minorities abroad, and the country’s welcome of refugees has made it home to as many as 100,000 Kurds. While the government has open contacts with some Kurdish political groups, it’s tended to align with other European nations in the way it treats Kurdish demands for self-determination. Sweden was the first country after Turkey to designate the PKK as a terrorist organization, in 1984.

3. So what’s Erdogan’s problem with Sweden?

Turkey has criticized Swedish officials for meeting with Kurdish politicians, citing one encounter between Foreign Minister Ann Linde and Elham Ahmad, who represents the PYD, the political wing of the YPG. When Prime Minister Magdalena Andersson was elected in 2021, it was partly thanks to the support of a Kurdish member of parliament, Amineh Kakabaveh. Her backing was secured in exchange for a pledge to increase cooperation between Andersson’s Social Democrats and the PYD. Another focus of tension is the Syrian Democratic Council, the political arm of a group of Kurdish-dominated forces in northern Syria. Turkey says the SDC is dominated by terrorists. Sweden says it cooperates with the SDC, but not with the YPG or the PKK.

4. What is Erdogan demanding?

He wants Sweden and Finland to publicly denounce the PKK and its affiliates as a condition to their joining NATO. According to Turkish officials who spoke to Bloomberg on condition of anonymity, Turkey also wants Sweden and Finland to clamp down on PKK sympathizers it says are active in their countries. Another condition, the officials said, is that Sweden and Finland end arms-export restrictions they imposed on Turkey in late 2019 in conjunction with many other EU countries after Turkey sent its army into Syria.

5. Will Sweden comply?

Any move that could be construed as kowtowing to Erdogan could be unpopular with Swedish voters, and Andersson’s government is likely to resist being drawn into negotiations over its extradition policy, for example, or its weapons exports. Instead, Sweden’s diplomats will likely try to enlist allies to pressure Turkey not to block Sweden’s entry into NATO.

6. How does Finland fit it here?

It appears to have been caught in the crossfire. The country has no significant Kurdish minority, with only about 15,000 Kurdish speakers residing in the country. Finnish policy makers say the country complies with EU terrorism designations, meaning it has also banned the PKK. Finland, like Sweden, did end arms exports to Turkey in 2019, but that trade had been small. In the past decade, Finland had exported about 60 million euros ($63.2 million) worth of goods classified as armaments to Turkey, including ammunition, protective equipment and armored plate.