Yuriy Vitrenko, the chief executive of Ukraine’s natural gas utility Naftogaz, had just made it down to an air raid shelter Saturday, along with three of his board members. He wouldn’t disclose the location because he wanted to avoid Russian troops or missiles — three of which had just landed within earshot.

One month into the war, the state-owned gas company provides a window into the conflict’s geopolitics and the extent of Ukraine’s destruction. Naftogaz serves 12 million households, Vitrenko said, but it has been forced to cut off 300,000 that have been heavily damaged by Russian missiles.

“If we cannot repair them, we have to shut them down,” Vitrenko said of the gas connections. “Sometimes an entire block [can be affected]. It can be also dangerous.” In the opening days of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, two of the company’s workers were killed inside a heating plant in Kherson, he added.

Naftogaz is also caught in a complex geopolitical game. Even as Russia rains missiles onto Ukraine, it is still sending approximately 30% of the gas it sells in Europe through the country it has invaded. And although Ukraine’s leaders have called for the continent to immediately halt imports of Russian gas, they are doing nothing to interfere with the gas flowing through pipelines at a rate of 40 billion cubic meters a year to customers including Germany, Austria, Italy, Slovakia, Hungary and the Czech Republic.

“It’s a very politically sensitive topic discussed at the highest political levels,” Vitrenko said. “We’re trying to persuade our partners in the European Union that they should reduce any purchases of Russian gas and oil or at least freeze all the money that Russia gets for the exports of energy.”

He said the money owed to Russia could go into escrow accounts.

If Ukraine took the initiative unilaterally and stopped the transit of natural gas supplies from Russia, Vitrenko said, the gas supplies would be diverted to other pipelines and make it to Europe anyway. That, he added, could make Ukraine even more vulnerable to Russian bombs.

“Then it’s not helping us in terms of cutting Russia from getting money for its energy exports, but also there is an increased risk for the gas infrastructure inside Ukraine,” he said. “We see it as a deterrent [against] more bombing and more destruction inside Ukraine.”

Many energy analysts have said that Russia has maintained its shipments of natural gas through Ukraine to show its reliability as a supplier that fulfills long-term contracts. In January 2020, the two nations signed a five-year deal for the amount now moving through Ukraine’s pipelines.

But Vitrenko said he doesn’t see it that way. “There’s a simpler, more straightforward explanation: Russia gets a half-billion to a billion dollars a day for energy exports,” he said. If Russia reduces its exports, “they wouldn’t be able to finance the current war, pay salaries to its soldiers and all the crowds currently supporting Putin. It will immediately impact the regime’s support, which is why they don’t want to disrupt this revenue stream.”

Anders Aslund, a senior fellow at the Stockholm Free World Forum and a longtime expert on Russian affairs, said both countries profit by keeping the gas flowing — Russia by selling the gas at high prices and Ukraine by collecting transit fees.

“If Europe continues importing gas from Russia, why shouldn’t Ukraine benefit from it?” Aslund said, noting that the International Monetary Fund last week forecast that Ukraine’s gross domestic product could dip 13.5% if the fighting stopped soon and as much as 35% this year if there is a prolonged conflict.

Amy Myers Jaffe, managing director of the Climate Policy Lab at Tufts University’s Fletcher School, said another reason to keep gas flowing was that Russia’s state-controlled gas company, Gazprom, has commitments to corporations in Europe.

“Gazprom would incur billions in financial contractual penalties if it fails to meet its contractual obligations,” she said. “Perhaps the Kremlin does not want to have to bail them out.”

Ukraine, she added, “needs and wants the support of NATO and therefore cannot take actions to upset the apple cart by cutting off Germany’s gas supply.”

Russia is now transporting some of its gas though newly built pipelines, such as one that crosses Turkey into southern Europe. In October, Russian President Vladimir Putin said the degree of “wear and tear” in Ukraine’s transportation system had prompted it to scale back the volume of gas in its latest agreement with Ukraine.

Ukraine’s own decreasing appetite for natural gas has also played a role in the flow of gas over the past decade or two. It once consumed 50 billion cubic meters a year, while producing 20 billion cubic meters annually. Before the Russian invasion, it had cut its consumption to just 30 billion cubic meters a year, slashing its reliance on imports by two-thirds.

Still, the conflict is fueling more greenhouse gas emissions whenever Russian missiles hit oil and gas infrastructure.

Less than five months ago, representatives from countries around the world gathered at the U.N. climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland, to set limits on greenhouse gas emissions. Ukraine, along with more than 100 other nations, signed the Global Methane Pledge to reduce emissions of the potent greenhouse gas by at least 30% by 2030. Russia did not, even though there have been large methane leaks at production, compressor and distribution sites along its vast pipeline network.

A couple months before Russia invaded Ukraine, Ukraine had unveiled a new compressor station that cut emissions there by 90%, Vitrenko said. There is an ongoing program to replace leaky metal pipes with modern plastic ones, he added, and Naftogaz had used robots to inspect pipes and spot defects in its distribution network.

“This was less because of environmental concerns, but more because of economic concerns,” the Naftogaz executive said.

Now, the world looks different, Vitrenko said. “This green transition should also focus on geopolitical sustainability, and it’s really intertwined with environmental sustainability.”

Recently, Russian forces bombed what Vitrenko called “rather big pipelines” for a number of days. “We could not stop the fire,” he said. “You can imagine the amount of methane emissions over there.”

He said one Russian missile hit an oil reservoir just a couple of kilometers from the shelter in which he was hiding. “So you can imagine environmental damage,” he said.

In light of the recent fighting, Ukraine’s priorities have been changed.

“The country’s at war, and there are still tens of millions of people in Ukraine who need heating, water, electricity, some critical utilities,” Vitrenko said.

This was a daunting prospect in normal circumstances. Now, he said, international donors will need not only to focus on food assistance, but to channel aid to Naftogaz, the country’s largest state-owned utility.

“When there’s a war, your expenses are up. People cannot pay,” Vitrenko said. “It’s not a business anymore. Basically it’s humanitarian assistance.”

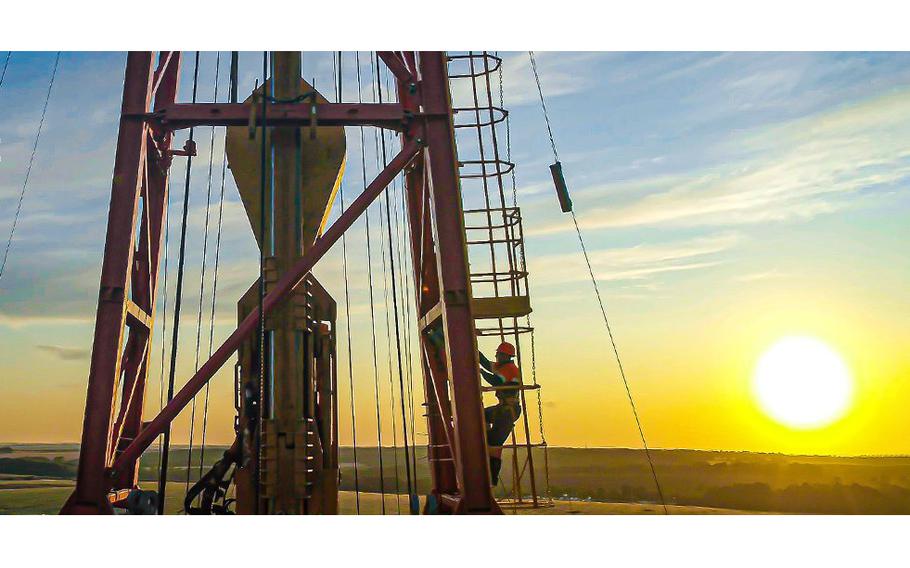

(Naftogaz/Twitter)