Europe

'I heard screams constantly': Inside the terror at Mariupol's bombed theater

The Washington Post March 26, 2022

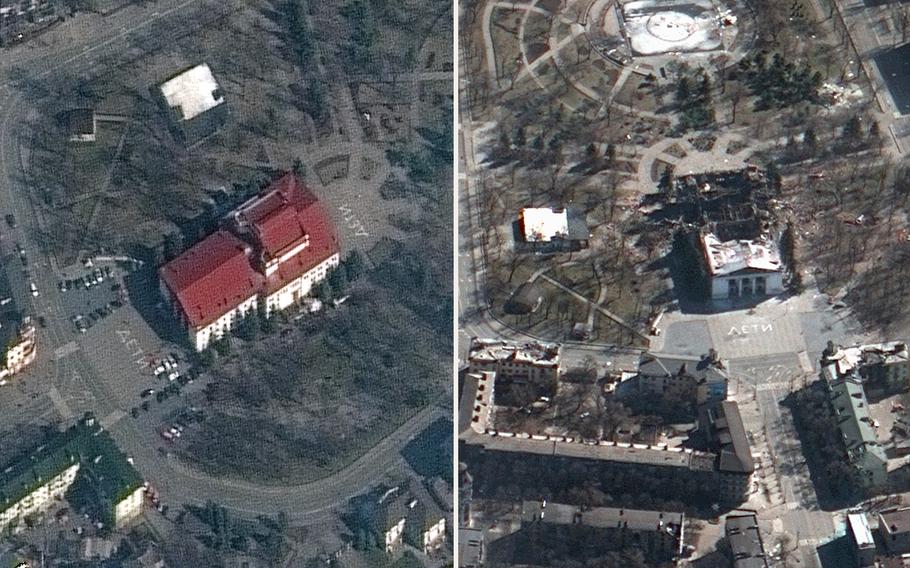

At left, a satellite image shows the Mariupol Drama Theater in Ukraine on March 14, 2022. At right, a satellite image shows the aftermath of the airstrike on the theater on March 19. (Maxar Technologies)

ZAPORIZHZHIA, Ukraine - The theater in Mariupol was supposed to be a safe haven.

Its walls were thick and sturdy. People had packed into the basement, foyer and the dressing rooms backstage in the hope of escaping Russia's bombardment of Mariupol, Ukraine's coastal city that President Vladimir Putin appears set on seizing at any cost.

"We thought maybe they'd see there were kids there and not bomb it," said Alexiy, 34, who left with his wife and 7-year-old son the day before an apparent Russian attack March 16 left parts of the building in ruin, leaving some people badly injured and officials struggling to determine a possible death toll.

"They even tied a white flag to the top of the building," he said. Like many people interviewed by The Washington Post, he spoke on the condition that only one name be published because of security concerns.

The fate of the hundreds of civilians sheltering in the building has gripped the world since Ukrainian officials accused Russia of bombing the building. Secretary of State Antony Blinken referenced the theater - with the words "children" in Russian painted on the floor outside - when he accused Moscow of war crimes earlier this week.

The Post spoke to seven people who were in the theater building in the 24 hours before it was hit in what Ukrainian authorities said was a Russian strike.

Two of the three people present at the time of the blast said that the basement, crammed with families with young children, was unscathed and people were able to flee afterward. They also said that those in the three-level foyer at the front of the building survived. But concerns remain for those in the backstage area, the main hall and the kitchen, which were all heavily damaged.

The lack of communications in Mariupol has hindered the flow of information. Ukrainian forces also have lost control of the area around the theater, preventing any rescue efforts or evidence gathering that could aid in investigations for possible war crimes.

Lyudmyla Denisova, Ukraine's human rights commissioner, has said police records show 1,300 people were registered in the building. But in the 48-hours before the strike, evacuations had begun.

On Friday, as the first videos emerged from the aftermath of the strike, the Mariupol City Council said it believed that as many as 300 people had been killed, citing eyewitness accounts.

Eyewitnesses say they are only guessing. But amid an information vacuum, the accounts give some indication to the potential toll.

___

The main hall, which was obliterated in the attack, had been deemed too dangerous to sleep in because of its exposed roof and huge chandelier. A video posted to Telegram on Friday, and verified by The Post, showed a mound of rubble.

"Under this rubble there may be a lot of people," said the person filming.

Mariia Rodionova, a survivor from the bombing in the Mariupol Theater, is seen in one of the parks of Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine, on March 24, 2022. (Wojciech Grzedzinski for The Washington Post)

One survivor, Mariia Rodionova, 27, who said she had been sleeping there despite the danger, said that around 50 people were in that part of the building. She said she went outside to get water for her dogs just moments before the strike.

She said she heard a whistling noise. The a man grabbed her and covered her, pushing her to the wall outside by the front entrance, she recalled.

"Debris was over us," she said in an interview after fleeing to Zaporizhzhia, about 135 miles northwest of Mariupol.

She thought she had ruptured an eardrum from the deafening sound. "There was a man with his face down in a pool of blood," she said. "Next to him was a woman trying to wake him up."

She said she desperately tried to find a way into the hall to get to her dogs and her first aid kit. "I went around a couple of times," she said. She said she became panicked.

"I didn't know where to go," she said. "To go into a bomb shelter, what's the point? It was a shelter. I just understood I had to leave."

She walked to Melekyne, 12 miles down the coast, and eventually got a bus out.

___

Bogdan Tymoshchuk, 17, who was staying in a dressing room backstage with his mother, estimated that there were around 100 people still there when he left in a convoy just an hour before the attack.

"It was families," he said.

They had been sleeping in the small dressing rooms. "We don't know what happened to them," he said by phone after fleeing to Lviv in western Ukraine.

Those staying at the theater describe a chaotic scene in the days leading up to the attack. The battle closed in and people started to risk escape, tying white flags to vehicles crammed with people and chancing it on the treacherous road out.

The theater had been one of three locations people had been told to gather. From here, they were to leave the city on humanitarian "green corridors" agreed with the Russians, officials said. The numbers swelled as word spread. At the peak there was barely space to lie down at the theater, survivors and others said.

But no help ever came. After the Ukrainian front lines collapsed - bringing the fight into the city - people began to self-organize to get out themselves.

"The explosions were getting closer," said Alexiy.

He said the first group of around 20 cars left the theater on March 14. Another left that evening.

"We were scared we'd get shot on the way," he said.

Finally, word came from the first group. They had made it safely. Alexei and others left early March 15.

Those without cars were desperate to get a ride out. Tymoshchuk had tried all day on March 15. He managed the following day, squeezing into a car with 10 people.

"There was constant fighting, constant bombing," he said.

___

As people left, others were still arriving at the theater.

Vladislav, 27, got there on the morning of the bombing to check if it would be a safer spot for his family.

"We knew there was food there," he said. Police and military dropped off supplies. There was a fire hydrant that people used for water. They cut down a nearby fence for firewood to cook on.

"I thought it wouldn't be possible for someone to bomb that place," said Vladislav. He said he was 30 feet inside the main door when blast hit at around 10 a.m.

"I just heard the bang," he said. He ended up on the floor - not sure if he instinctively took cover or was knocked down by the explosion.

"I followed people out," he said. A video posted online on Friday showed people covered in dust making their way a stairwell in the theater, including a woman carrying a young baby.

"We went into the basement from the other side," said Vladislav. "It wasn't damaged."

He waited 15 minutes in the basement before fleeing on foot to Melekyne.

Nadezhda, who had moved to the shelter on March 8 after her neighborhood was heavily shelled, was in the basement at the time of the attack.

"Saying the basement was filled to the brim, doesn't do it justice," she said. At first she slept on the third-floor of the foyer with her daughter. They moved to the basement March 15.

When the blast hit, her son-in-law and daughter had just been preparing to get some water. Her son-in-law was tying his shoe and was knocked over from the force of the blast. The air filled with dust. The basement door blew out.

"I was panicked," she said.

She ventured outside, where she was met with a scene of horror. She and others tried to help treat the wounded with makeshift bandages made from strips of material. She said that there were body parts scattered around. A man had part of the back of his leg ripped off.

She tried to make a tourniquet, and said she helped as much as she could but had to stop. "I heard screams constantly, you could go crazy for it," she said.

___

The Washington Post's David Stern in Mukachevo, Ukraine, contributed to this report.