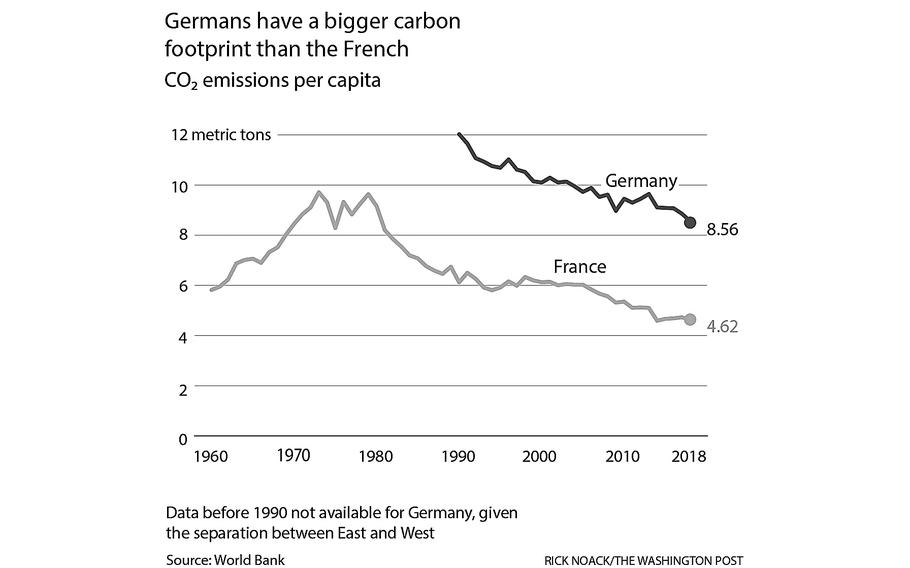

France, which relies heavily on nuclear energy, has lower CO2 emissions per capita than does Germany, which has a strong anti-nuclear movement. ()

FESSENHEIM, France - When President Emmanuel Macron announced the revival of nuclear energy in an address to the nation last month, residents of a small town in eastern France initially thought they had misheard him.

"For the first time in decades," Macron said in the televised speech, France "will relaunch the construction of nuclear reactors."

Fessenheim had just begun to come to terms with the closure of its nuclear plant last year, in what the government had said was a "first step" in a "rebalancing" of energy sources. But while Macron remains committed to increasing investments in wind and solar energy, and to putting an end to the burning of coal, his remarks in November confirmed that France isn't giving up on nuclear technology, its primary source of energy.

France is behind only the United States in the number of its operational nuclear reactors, and it is first in the world in its reliance on nuclear energy. A prior plan to reduce that reliance, so that no more than half of France's electricity comes from nuclear power by 2035, is in doubt.

Macron's government argues that investments in nuclear power will allow France to keep energy costs in check, control its own supply and meet its climate goals. France is leading a group of mostly central and eastern European countries that are pushing the European Union to add modern nuclear energy to a list of "environmentally sustainable economic activities."

In Fessenheim, that has sparked hope that the town - where the power plant supported more than 2,000 jobs - may get a second chance. "We don't want to be the sacrificed and forgotten ones," said Mayor Claude Bender, who welcomed Macron's speech as a "positive surprise."

The president of the surrounding Alsace region, Frédéric Bierry, has urged Macron to consider Fessenheim as a possible future site, calling the old plant's closure a "financial," "social" and "economic" scandal in the face of a warming climate.

But one of the biggest obstacles - for Fessenheim and for Macron's broader plans - lies about half a mile to the east of the town's old nuclear plant. That's where France ends and Germany begins.

The new German economy and climate minister, Green party member Robert Habeck, was among the politicians who signed a statement celebrating the closure of the Fessenheim plant. The German government has argued that nuclear plants are too risky, and too slow and costly to build, to be a solution to the climate crisis. Germany's outlook is influenced by nuclear accidents, such as the 2011 Fukushima meltdown in Japan. And Berlin points to reports like one this past week, of cracks in the pipes at a French nuclear reactor, as evidence that plant safety remains a problem.

Germany is among a group of skeptics, including Denmark and Austria, that wants Europe to shut down its remaining nuclear plants and that fiercely oppose a climate-friendly designation for nuclear power, which would signal to green investors that nuclear energy is worthy of financing.

The controversy may come to a head within days, with the European Commission expected to make a decision just before its Christmas break.

- - -

Perhaps no place symbolizes European divisions on nuclear energy more than Fessenheim.

The 1,800-megawatt nuclear power station here was built in the 1970s - a gigantic white block with two towering reactor-containment buildings, rising from behind a forest outside the town.

On the French side of the border, it was a source of pride, and of economic benefits. The power plant was by far the biggest employer in the area. And taxes from the plant helped subsidize the development of the town, including sports fields, schools and a shopping center.

At its peak, Fessenheim "had everything," said resident Laurent Schwein, who noted that his family's restaurant had to be repeatedly expanded to accommodate the surge in residents and visitors.

Schwein said locals weren't concerned about the power plant's safety - even its location near earthquake-prone seismic faults.

But on the other side of the border, the region near Fessenheim has long been part of Germany's anti-nuclear movement. When a radioactive cloud rose from the Chernobyl plant in 1986 and moved toward Western Europe, Fessenheim quickly became a rallying point for West German activists.

The activists raised alarms every time there were reports of safety issues at the plant: cracks in a reactor cover, a steam leak that injured workers, internal flooding that led to an emergency shutdown. They worried about a Swiss study that determined that the seismic risks in the region had been underestimated.

The Fukushima disaster, triggered in part by an earthquake, compounded concerns. In the months after Fukushima, the German government decided to permanently close nearly half its nuclear plants and limit the years of operation of the rest. In France, the response was more muted. But the following year, campaigning for the French presidency, François Hollande promised to close Fessenheim if he were elected.

It took eight more years and a subsequent administration for that to happen. But when the Fessenheim nuclear plant was taken off the grid in June 2020, activists in the German border town of Breisach celebrated what they saw as France's finally coming to its senses. Just a 10-minute drive from Fessenheim, they assembled on a bridge near the town's 800-year-old church, waving banners that showed a smiling red sun and a crossed out nuclear symbol.

Activist Eberhard Bueb said they refrained from toasting with Champagne or beer out of respect for the French that day. "But for us, it felt like celebrating Easter and Christmas at the same time," he said. "It was such a relief."

The mood in Fessenheim was understandably different. Bender, the mayor, recalls tears among locals. To this day, protest banners plastered to the fence condemn the plant's closure as a "historic mistake" and as a political "sacrifice" to please skeptics.

"A part of ourselves was taken away from us," the mayor said.

- - -

In his office, Bender keeps a drawing that shows the German-French border: a shuttered nuclear power plant on the French side, and a newly-reopened hard coal power station on the German side. Speech bubbles capture beer-drinking German and crying French workers reaching the same conclusion about their neighbors: "They haven't understood anything!"

Like many nuclear advocates in France, Bender argues that Germany's anti-nuclear stance and continued reliance on fossil fuels are at odds with its self-image as a leader on climate.

Germany is largely responsible for an air pollution death toll that amounts to "multiple Chernobyls every year," he said.

Germany emits about twice as much carbon dioxide per capita as France does. When it phases out its last nuclear power plants next year, it will be forced to rely on coal and other polluting energy sources to fill much of the gap for years - which helps explain why the country continues to raze villages to make way for coal mines.

Macron's government, meanwhile, says that sticking with nuclear power will help France meet its commitment to be carbon-neutral by 2050 - and is preferable to a continued reliance on fossil fuels.

"If we look at it from the carbon perspective, nuclear is one of the best in class," said Alexandre Danthine, a senior associate with Aurora Energy Research.

Environmental activists in Germany acknowledge that continued reliance on coal is a problem even in the medium term. But they are optimistic about how quickly the country can ramp up alternative energy.

Germany's Green party, in its position as part of the new ruling coalition, has vowed to increase spending significantly on renewables and to limit energy price spikes for consumers. It wants renewables to account for 80% of electricity by 2030, up from the present target of about 50 percent.

For German politicians and activists, the idea of nuclear power as green or sustainable is anathema. They talk about the potential for accidents with catastrophic environmental consequences. They note the problems associated with the long-term storage of deadly radioactive waste. They say they don't want to draw investment away from wind and solar.

German anti-nuclear and environmental activist Stefan Auchter said his country's path will be validated when the next Chernobyl or Fukushima comes. He compared the use of nuclear energy to playing Russian roulette.

"Who would really believe that we can get this done without a mistake, when we can't even build an airport?" he said, referring to Berlin's new airport, which opened nine years behind schedule.

- - -

At the World Nuclear Exhibition in a suburb of Paris this month, a renewed sense of confidence was on display. Industry insiders lunched beneath a miniature reactor roof, and a long line of people waiting for food stretched past a decontamination expert's booth. Celebratory Champagne was everywhere.

Macron didn't include any details in his announcement about new reactors. He may have been referring to what are known as EPRs, large pressurized water reactors that are supposed to offer advances in safety and efficiency over conventional reactors while producing less waste. The French energy firm EDF submitted a feasibility study to the government in the spring to build six new reactors of that sort.

But a new generation of cheaper, safer and smaller nuclear reactors - known as small modular reactors, or SMRs - is reawakening interest in parts of Europe, in the United States and elsewhere.

"The terms of the conversation around nuclear energy in Europe are changing," E.U. Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson said in a speech in November.

France's export hopes largely rest on those small models, which would compete with SMRs being developed by the United States, Britain and Canada.

"The small modular reactors that are coming in the next decade all guarantee high safety," said Renaud Crassous, the director of EDF's small nuclear reactor project. He expressed hope that skeptical countries could be swayed by the novel technology to regain trust in nuclear energy.

In the town of Breisach, on the German side of the border near Fessenheim, Mayor Oliver Rein is still skeptical.

He had anticipated that the closure of the nuclear plant would pave the way for joint Franco-German renewable-energy projects. But if the neighboring town pursues its "ridiculous" idea to reawaken its nuclear plant, this "Franco-German process will be ruined," he said.

"When a vegan business wants to settle, it probably won't move next to a slaughterhouse," he said.

Rein suggested that France's new nuclear push may be a short-lived phase ahead of next year's presidential election. But a recent survey suggested that a slight majority of the French are once again in favor of nuclear energy, and Macron's most serious challengers for the presidency - all of them on the right or far-right of the political spectrum - have either echoed his comments or supported even heavier reliance on nuclear energy. Far-right candidate Marine Le Pen has called for the prompt reopening of Fessenheim, and Éric Zemmour included footage of reactors in the video that kicked off his presidential campaign.

Still, some in Fessenheim sense that the next nuclear era may not play out in their town.

"With the pressure from the Germans, it'll be difficult," said Jean-Yves Tretz, 63, a retired plant worker.

Claude Ledergerber, a French anti-nuclear activist who is part of the plant's control commission, said reactivation is technologically "no longer possible." Too many elements have been removed, he said.

Playing a round of Pétanque, a French outdoor bowling game, restaurant owner Schwein said he is prepared for the last workers to leave the plant when decommissioning has been completed in the coming years.

He has installed solar panels.