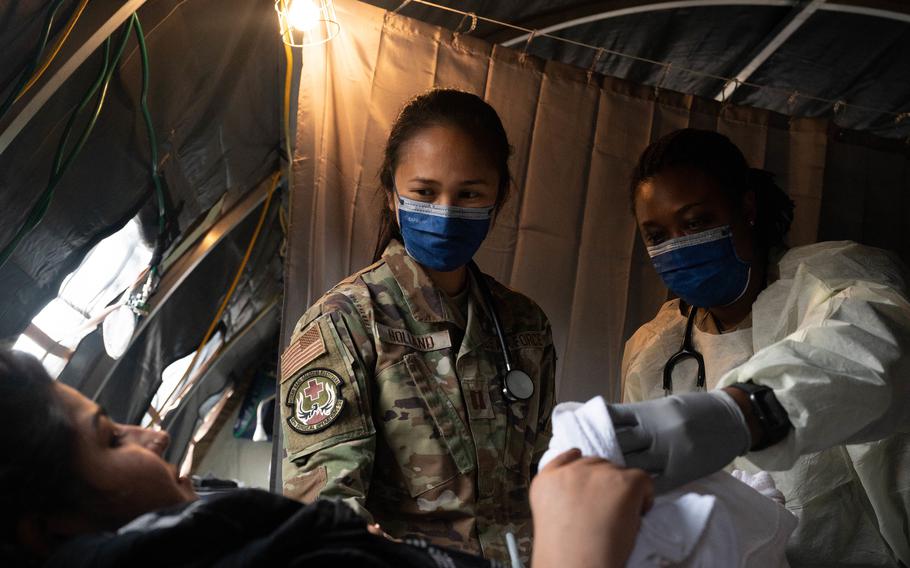

Air Force Capt. Danielle Holland, left, an OB-GYN physician at RAF Lakenheath, United Kingdom, and U.S. Army Lt. Col. L. Rene Key, director of the Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center OB-GYN course at Ft. Hood, Texas, provide medical care to an evacuee at Ramstein Air Base, Germany, Aug. 31, 2021. A field hospital and medical tent with OB-GYN care is available for expectant mothers and newborn babies in need of emergency treatment. (Taylor Slater/U.S. Air Force)

RAMSTEIN AIR BASE, Germany — The conditions in the tent near the flight line as overnight temperatures dipped into the 40s clearly weren't ideal for giving birth.

There wasn’t time to get the Afghan woman in labor to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, about 15-30 minutes away by ambulance, depending on traffic.

“So we delivered in the tent,” said Capt. Danielle Holland, an Air Force obstetrical and gynecological physician.

She was recounting an emergency that occurred early on in Ramstein’s mission to support Afghan evacuees after the end of 20 years of war. It was the woman’s ninth baby and a childbirth she’ll likely remember fondly despite the harsh conditions.

“She told our translator that it was the best delivery experience she ever had,” Holland said. “I was happy to hear it was the best but also sad that a tent delivery in Germany while being evacuated is your best birth experience.”

Tending to the scores of pregnant women who have poured into Ramstein since the first evacuation flight arrived Aug. 20 has been a challenge for U.S. military medical providers accustomed to Western standards of care.

The evacuated women arrive mentally and physically exhausted, often dehydrated and malnourished.

In the field hospital at the base, medical staffers have needed to improvise. For example, they've used examination tables that don't have stirrups and a head lamp for proper lighting.

It’s hoped that the lessons learned will improve how the military provides health care in similar situations, said Maj. Suzanne Stammler, an Air Force OB-GYN physician.

“Humanitarian-wise, in every conflict, there’s always women and children,” she said.

Stammler and Holland are part of an OB-GYN team that arrived at Ramstein a few days after the first evacuees. They’re with the larger 68-member Expeditionary Medical Support team deployed from RAF Lakenheath in England to support Ramstein and LRMC.

The EMEDS team early on worked from tents and recently set up a field hospital inside the Southside Fitness Center.

Together with medical personnel at LRMC, they’ve delivered 21 babies as of Friday and provided care to women who miscarried or who need basic prenatal or postpartum care, from lactation help to fluids to treat dehydration, officials said.

“The ability to provide care is a very big privilege because for these women, not having access to the basic things that we have access to every day is a hard thing to see,” Stammler said.

In the first three weeks, the OB-GYN team at Ramstein cared for more than 120 women, a number that’s “the tip of the iceberg,” Stammler said.

“I know there’s a huge (cultural) stigma for women to even ask for help,” she said.

Many of the women have had no prior prenatal care and didn’t know how far along their pregnancies were, the doctors said. The OB-GYN team at Ramstein uses ultrasound technology to estimate gestational age and delivery date, “but even that’s challenging because their babies are generally smaller,” Holland said.

“One patient told me she continues to breast feed until she’s pregnant again,” Holland said. “That’s her gauge.”

Without prenatal or medical records, providers don’t know whether a pregnancy is high-risk, said Air Force Maj. Khimea Sayles, the clinical nurse officer in charge of labor and delivery at LRMC.

But so far, deliveries have been smooth and babies have arrived healthy, she said. Eighteen babies have been delivered at LRMC.

The women have all declined narcotics for pain management during labor, she said.

“They’re true rock stars ... they make it look easy,” Sayles said.

Many of the women tend to be in poor health when they seek care, a condition exacerbated by their harrowing journey since fleeing home.

“Things are just so different for them, and they pull back on everything; they don’t drink, they don’t eat,” Stammler said.

LRMC gives the women a bassinet with diapers, wipes and other items. They've also started giving them bag lunches when discharged to help supplement meals at Ramstein. Still, quite a few have miscarried, Stammler and Holland said.

It’s hard to pin pregnancy loss on the physical and emotional stresses the women are enduring versus chromosomal imbalances, the most common cause of miscarriages, Stammler said.

But those cases have been challenging to manage because doctors don’t want to send a woman on an eight-hour trans-Atlantic flight if she might miscarry because there is a danger of severe blood loss, she said.

Usually, the women defer treatment decisions to their husbands.

There are exceptions, such as a married, pregnant woman who attended Kabul University and was an English teacher.

“For them as a couple, she drove the boat,” Stammler said. “We recruited her to help translate.”

The husbands aren’t in the delivery room for their child’s birth, Sayles said. The men insist that their wives be treated by women only.

At LRMC, nurses have been doing many of the deliveries, with a male doctor standing by in case of emergency.

Some patients have also sought options that weren’t available to them in Afghanistan.

One patient in her mid-30s said she would like to use contraception after having her ninth baby. Her husband agreed, Holland said.

“It was an extraordinary moment,” she said.