Europe

Supporters warn against sending ex-Guantánamo inmate back to Russia

The Washington Post September 4, 2021

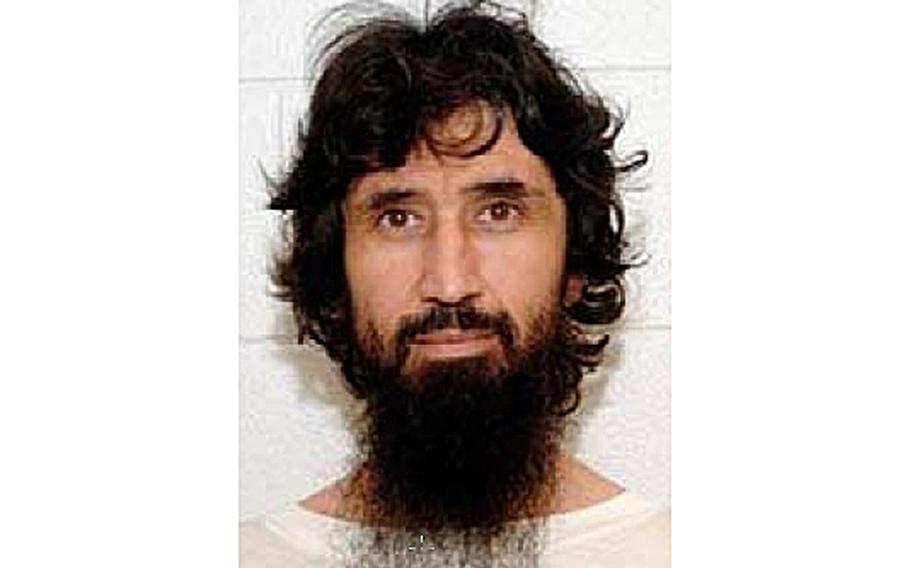

Ravil Mingazov (Official Guantanamo picture via WikiMedia Commons)

A former Guantánamo Bay inmate who has been imprisoned in the Persian Gulf since his 2017 release from U.S. custody may now be forcibly repatriated to Russia, where he could be subject to further detention and abuse, his family and lawyers have warned.

The case of Ravil Mingazov — whom the United States detained without charge for nearly 15 years before sending him to the United Arab Emirates — underscores the challenges President Joe Biden faces as he attempts to shutter a facility that came to symbolize American excesses after the 9/11 attacks.

The Russian national is one of roughly two dozen detainees the Obama administration moved to the UAE, where attorneys and relatives say the men, instead of entering into a temporary rehabilitation program, were locked in years of secretive detention.

Mingazov, 53, has been adamant about his fear of being sent home to Russia, where other returned Guantánamo inmates have been harassed, jailed and beaten, rights groups say. One was killed in a police raid.

"He must have said that to me 50 times," said Mingazov's attorney, Gary Thompson. Being sent to Russia has "always been his greatest fear to the point of: 'Promise me, no matter what, you won't let that happen.' "

Russian authorities now appear to be making preparations for Mingazov's return, Thompson said, just as Emirati authorities quietly accelerate efforts to discharge the men for whom the UAE took responsibility in a resettlement deal with the United States. The Russian embassy did not respond to requests for comment.

Already this summer, the UAE has repatriated six Yemenis despite concerns about sending them to a nation engulfed by civil war. In 2019, the UAE repatriated four Afghans. One died a few months later of health issues that his family attributed to abuse suffered in U.S. and Emirati custody. Roughly a dozen prisoners remain in the UAE.

The Biden administration, eager to secure additional agreements to resettle some of the remaining detainees at the U.S. facility in Cuba, has remained mostly silent about the handling of the former U.S. prisoners. But officials have quietly urged Emirati officials not to send Mingazov back to Russia.

"The United States is aware of and deeply concerned by reports regarding the potential forced repatriation of a former Guantánamo Bay detainee to Russia from the UAE," a State Department official said, speaking on the condition of anonymity under rules established by the agency.

Mingazov's 22-year-old son Yusuf, who has only ever known his father through phone calls from prison, likened repatriation to a death sentence.

"They will kill him," he said.

In a statement, the Emirati embassy in Washington said it was coordinating closely with the United States on the fate of remaining detainees. "The UAE has coordinated directly with the U.S. on the transfer, rehabilitation and release of about two dozen detainees, all third-country nationals, previously held at the U.S. facility at Guantánamo Bay," the embassy said.

According to a person familiar with Emirati officials' deliberations, the UAE will not make a decision about Mingazov's disposition "without the consent of the United States."

Mingazov grew up in Tatarstan, a Russian republic 600 miles east of Moscow, with a large Muslim population. He studied ballet and danced with the army ballet troupe in the late 1980s.

According to accounts he later provided to U.S. officials, Mingazov was harassed by Russian authorities when he tried to advocate for the rights of fellow Muslims. Frustrated, he fled the country, making his way to Afghanistan.

When the U.S. bombing of Afghanistan began after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, Mingazov said he traveled to Pakistan. Pakistani police arrested him there in 2002 and handed him over to the Americans, who his lawyers allege tortured him at a U.S. base in Afghanistan. In March of that year, he arrived at Guantánamo.

In his decade and a half at the prison, Mingazov, like most of the more than 700 men and juveniles who were sent there in the years after 9/11, was never charged with a crime. In 2010, a federal judge sided with his lawyers in ruling that the government had failed to substantiate its claims that he joined al-Qaida and an Uzbek militant group.

In January 2017, Mingazov's attorneys were elated to learn he would be among a group of detainees moved to the UAE. The move was part of an eleventh-hour scramble to resettle detainees before Donald Trump, who had promised to halt detainee transfers and even bring new prisoners to Guantánamo, took office.

Many of the nearly 200 detainees the Obama administration resettled overseas adapted to their new surroundings and married or found work. Most lived on their own but were subject to government monitoring.

Others did not fare so well. Some detainees had trouble acclimating to new cultures and languages. Several violated travel restrictions or were deported from their host country.

One former official said the resettlements were envisioned as a chance for prisoners to start over. "This sort of post-transfer stability promotes both the well-being of the former detainee and the security of the United States," he said.

Former officials say the UAE, an important Middle Eastern ally, agreed to accept Guantánamo prisoners as a favor to President Barack Obama.

According to a person familiar with the 2017 transfer that included Mingazov, Emirati officials appeared to share the U.S. vision. They said they would build a dedicated facility for the men and outlined rehabilitation steps that would include access to special clerics, similar to programs that Saudi Arabia and Oman had launched. "It was taken seriously," the person said.

But many of detainees' relatives said the men, after their arrival, largely disappeared. While some of them reported satisfactory conditions, others said their circumstances were worse than Guantánamo. At least in American custody, they had access to lawyers and the International Committee of the Red Cross.

Relatives were able to glean only minimal information about Mingazov's circumstances, including about where he has been held, but say what they heard was concerning.

Mingazov told his family he was left in solitary confinement for extended periods. His requests for books were denied. He also suffered medical problems, including dental and eye afflictions, and did not receive needed treatment, his son said.

"It was always his dream to go to an Arab country. He thought it was like winning the lottery," Thompson said of the UAE transfer. "Little did we all know it was, luck of the draw, a terrible place to go."

According to Mingazov's son, who now lives in the United Kingdom, calls from his father have been rare, never lasting more than a few minutes. "Every time he'd say something about [his treatment in the prison] they'd shut off the call," the younger Mingazov said.

One of the Afghans repatriated in 2019 described the treatment by Emirati guards as rough and demeaning. "We were shocked because we expected to be treated as guests rather than prisoners," he told reporters after his return to Afghanistan.

Former U.S. officials said they were surprised by how the UAE detention played out, suggesting what occurred may have been shaped by Trump's hard-line approach to terrorism suspects and the fact that he shuttered the State Department's Guantánamo closure office, greatly reducing oversight of transferred prisoners.

A few months ago, several Russian government agents appeared at Mingazov's mother's apartment in Tatarstan, his attorney and son said. They asked her to verify Mingazov's identify in a photo and confirm biographical information. "They said they were making a passport," his son said.

His family was gripped by fear. They had requested asylum for him in Britain, but have gotten no indications his petition would be granted. A British government representative declined to comment.

"I just want some justice," the younger Mingazov said. "Why is he still sitting there for no reason?"

Already, half of the former U.S. prisoners held in Emirati custody have been repatriated to Afghanistan or Yemen. According to the State Department, Emirati officials affirmed the repatriated Yemenis agreed to be sent home. More Yemenis are expected to follow.

Those events, and expectations that Mingazov could soon be transferred, have stirred outrage among relatives, advocates and even experts appointed by the United Nations. Former officials say forcible or coerced repatriations would violate the provisions of resettlement deals, which prohibited refoulement, or forcible repatriation to nations where individuals will face persecution.

"This is a result of a failure of the U.S. government to engage with the Emiratis during the entirety of the Trump administration," said Ian Moss, who worked on Guantánamo issues during the Obama and Trump administrations. "There's an opportunity and an urgent need for the Biden administration to engage on post-transfer issues like the one in the Emirates while simultaneously working to transfer other detainees."

No matter where Mingazov is sent, the controversy surrounding the UAE resettlement is likely to compound the difficulties the Biden administration faces as it attempts to broker additional transfers.

Officials hope to resettle at least 10 of the 39 prisoners remaining at the facility. A dozen others are at some stage of a military trial process. Previous attempts to bring detainees to the mainland United States for imprisonment or trial have been blocked by Congress. Republican opposition to closing the prison remains intense.

The Biden administration has not yet appointed a dedicated official for Guantánamo's closure. Cliff Sloan, a Georgetown University law professor who served as special envoy for Guantánamo closure during the Obama administration, believes Biden can close the prison, now housing so few detainees. He acknowledged it wouldn't be easy.

"I think with closing Guantánamo, we're five yards from getting into the end zone," he said. "But sometimes the last five yards are the most challenging."