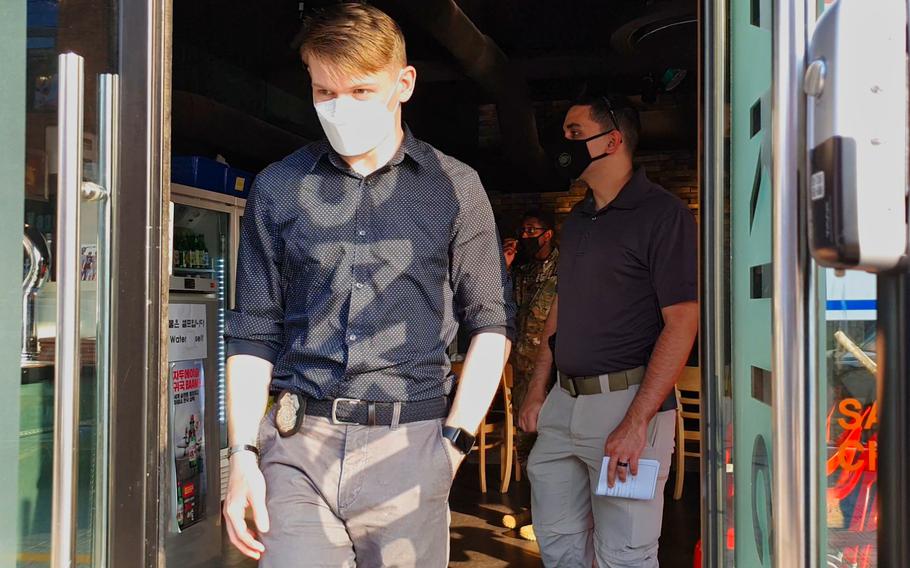

Spc. Jacob Kincer and Spc. Nicholas Woznick, investigators with the 557th Military Police Company, patrol outside the gates of Camp Humphreys, South Korea, Friday, May 1, 2020. (Matthew Keeler/Stars and Stripes)

Stars and Stripes is making stories on the coronavirus pandemic available free of charge. See other free reports here. Sign up for our daily coronavirus newsletter here. Please support our journalism with a subscription.

CAMP HUMPHREYS, South Korea — Routine U.S. military police patrols into the entertainment district outside Camp Humphreys took on new meaning when coronavirus cases, seemingly curbed in South Korea, resurfaced with the loosening of social-distancing measures.

Just a week ago, new cases were being reported in the single digits. Now, that number has grown nearly eight-fold following an outbreak in Seoul’s popular nightlife district in Itaewon. Anyone who visited clubs and bars in the area between April 30 and May 6 is likely to have been exposed to the virus, according to the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website.

Courtesy patrols by military police have been standard practice for years. Police routinely visit drinking establishments outside the gates of nearly every U.S. military installation in the country to ensure service members are behaving.

Now, because of the declaration of a public health emergency by U.S. Forces Korea commander Gen. Robert Abrams, military police are also peering inside restaurants and barbershops to ensure U.S. personnel are complying with health protection condition restrictions.

USFK personnel must avoid gatherings of more than 15 people. Off-base activities such as dining at restaurants and visiting barbershops, bars, movie theaters and amusement parks remain prohibited.

“We need to stop the virus,” said Sgt. 1st Class Alex Reyes, the provost sergeant for Area III, which encompasses Camp Humphreys. “The way we can do it as law enforcement professionals is by actually visiting the hotspots and making sure everyone is complying with [restrictions]."

The Camp Humphreys task force consists of a noncommissioned officer, three soldiers and three South Korean troops serving as Korean Augmentation to the U.S. Army, or KATUSAs.

“The objective is to be a visible presence in the town checking bars, restaurants and clubs making sure that people and our soldiers are not violating the [health protection condition] restrictions or committing any crimes,” Reyes said.

The soldiers rotate shifts, taking roughly an hour to walk the entertainment district and make sure U.S. personnel are practicing social distancing and not remaining stationary for too long.

However, the patrol teams have essentially zero jurisdiction beyond the installation. They can’t detain or demand anyone they believe has an affiliation with the garrison to provide identification.

For example, the team approached a young American man with a military-style haircut exiting an off-base barbershop on May 1. Questioned, he denied any affiliation with Camp Humphreys or USFK and was allowed to go on his way.

For that reason, Reyes said, the patrols are usually accompanied by local police officers.

“We have the backup,” Reyes said. “When we go out on town patrols, we meet up with our Korea national police counterparts. They have primary jurisdiction off post.”

Anyone who refuses to identify themselves to South Korean authorities may be taken into custody and turned over to military authorities, Reyes explained.

Violators are escorted back on post and their chain of command or supervisors are notified of the violation.

Several service members have been reduced in rank and Defense Department civilians barred from all U.S. installations in South Korea for breaching the public health regulations.

The virus outbreak has proven to be an unexpected adversary for junior law enforcement.

“This wasn’t something I was expecting when I first joined,” said Spc. Jacob Kincer, an investigator with the 557th Military Police Company. “It’s all about changing with the tide that you’re thrown into and figuring out what flow you need to go with to be able to protect the base, no matter what threat may be out there.”