The USS Arizona burns after being struck by Japanese bombs during the attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on Dec. 7, 1941. (U.S. Navy/National Archives)

A Virginia real estate agent is close to finishing a self-appointed mission aimed at collecting enough DNA to meet the threshold for exhuming dozens of unknown Pearl Harbor victims who were serving aboard the USS Arizona.

Kevin Kline hopes that will lead to identification of the service members’ remains, a task once deemed unfeasible.

In 2023, he started Operation 85, an advocacy group that has helped the Defense Department track down the majority of the 592 families thus far that have either given DNA or are in the process of submitting a DNA kit, Kline said Tuesday. The group represents nearly 1,200 family members of the Arizona’s crew, he said.

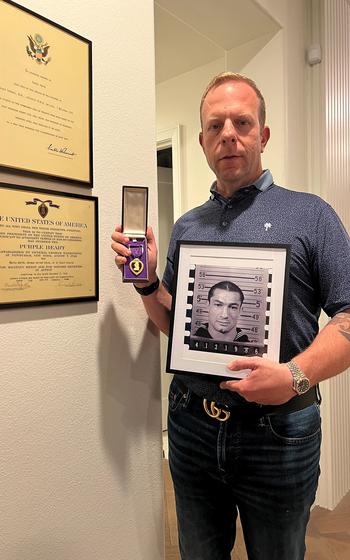

Kevin Kline, executive director of the USS Arizona family group Operation 85 and grandnephew of Arizona sailor Petty Officer 2nd Class Robert Kline, poses with Kline's Purple Heart in his Virginia office on March 28, 2025. (Operation 85)

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency requires a general threshold of family samples from 60% of the “potentially associated service members” before it will disinter the remains for identification, according to Defense Department regulations.

In the case of the Arizona, Kline takes that to mean samples from 643 distinct families, or 60% of the current missing and unaccounted for. The Navy, however, is putting the required number at 681, spokesman Lt. Cmdr. Stuart Phillips, said in an emailed response to questions.

It is unclear how that figure was determined, but Kline said Operation 85 will reach the higher number regardless.

The U.S. government had just 25 families on file shortly before Operation 85 began their efforts, according to a Navy report to Congress in March 2022.

“We’ve done this in under two years,” Kline said. “Operation 85 should be able to meet the DOD 60% threshold goal by this summer, but we do not have any plans of stopping the search for family once we hit a specific number.”

He is the grandnephew of Petty Officer 2nd Class Robert Kline, a gunner’s mate who remains missing from the Japanese attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet in Hawaii on Dec. 7, 1941.

Petty Officer 2nd Class Robert Kline, a gunner’s mate aboard the USS Arizona, was killed in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on Dec. 7, 1941. (Kevin Kline)

Kline described himself as a “random guy who … was told no by the DPAA, that it couldn’t be done,” adding that he “got so mad” that he decided to do it himself.

The Pearl Harbor attack claimed the lives of 1,177 sailors and Marines on the Arizona. Today, 1,072 remain missing, the DPAA website states.

Answering family member questions in 2021, a year before Kline began his effort, DPAA director Kelly McKeague called the project unfeasible and said preliminary discussions had taken place about potentially entombing the unknowns back in the ship.

Disinterring the unknown sailors and Marines from the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific would mean DPAA had to get family reference samples, McKeague said in the question-and-answer session uploaded to YouTube by Operation 85.

“It’s not a proposition that makes pragmatic sense,” he said.

Over 900 members of the crew’s 1,512 men remain interred in the ship’s submerged hull, which is today part of the Pearl Harbor National Memorial complex.

The USS Arizona navigates off New York City during its maiden voyage in November 1916. (U.S. Navy)

There are 86 sets of likely comingled remains associated with the Arizona buried as unknowns in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, otherwise known as the Punchbowl, and an additional 55 that have no known ship affiliation, McKeague wrote in a letter to Kline on Feb. 19. It is unclear whether the 55 would be disinterred as part of the Arizona effort.

A Navy report to Congress in March 2022 estimated it would cost approximately $2.7 million and take 10 years to track down enough families for DNA to reach the Defense Department threshold for disinterment, the report states.

Kline and his group have tracked down 567 families in about two years, at a cost of around $70,000, put up by Kline. By comparison, the report drafted by the Navy cost $83,000 to produce.

Phillips defended the Navy’s cost estimate, saying a similar project involving the USS Oklahoma had been extremely challenging. The Oklahoma also came under attack in the Pearl Harbor incursion and capsized, killing 429 of those aboard.

As of April 3, the Navy and Marine Corps had officially processed the DNA of 509 families, according to reports from the two services’ casualty offices that collect the samples.

Priority for family reference sample collection is given to what DPAA designates as “official projects,” Phillips said, adding that the Arizona is not currently an official project.

A woman pays respects at the USS Arizona Memorial in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on Dec. 5, 2022. The memorial honors 1,102 of the 1,177 sailors and Marines killed in the Japanese attack on Dec. 7, 1941. (Ernesto Bonilla/U.S. Navy)

After a family trip to the Arizona memorial in 2022, Kline attended a DPAA family update meeting and was told the agency would not identify the unknowns from the ship anytime soon.

Kline decided to put his business on hold and undertake the effort. He enlisted Melinde Lutz Byrne, one of the country’s top forensic genetic genealogists, in June 2023 and efforts really took off.

Different types of DNA carry different genetic information that is passed to certain relatives. Until January, the government was not accepting what are known as autosomal single nucleotide polymorphism DNA samples, such as those of paternal nieces and grandchildren, Kline said.

This sort of DNA is beneficial for distant-donor relationships and highly degraded skeletal remains, which includes nearly 100% of DPAA’s cases, said Dawne Nickerson, a spokeswoman for the medical examiner’s office at Dover Air Force Base, Del., which does the testing.

As a result of the policy, the government was limiting the field of potential donors.

James Silverstein, a California attorney and maternal grandnephew of Petty Officer 2nd Class Harry Smith, is angry he was turned away from giving a sample prior to DPAA’s announcement.

I have a “deep concern over how this process has played out,” Silverstein said. “This is such a basic request. This is something that the government should be happy to do, and yet it’s been anything but that, and these (service members) deserve better and the families deserve better.”

James Silverstein, grandnephew of USS Arizona sailor Petty Officer 2nd Class Harry Smith, poses with Smith's Purple Heart and the associated documents on March 27, 2025. (James Silverstein)

The change on autosomal single nucleotide polymorphism DNA inched Operation 85 closer to the line by 45 families in a little over a week, Kline said.

Kline and Byrne believe the government’s accounting needs to be overhauled and certain tasks farmed out to the private sector. He wants to use the infrastructure they’ve built to help other groups find closure.

“I don’t want to put this away,” Kline said. “I think other people can use what we’ve built.”