Asia-Pacific

How China built a $50 billion military stronghold in the South China Sea

The Washington Post October 31, 2024

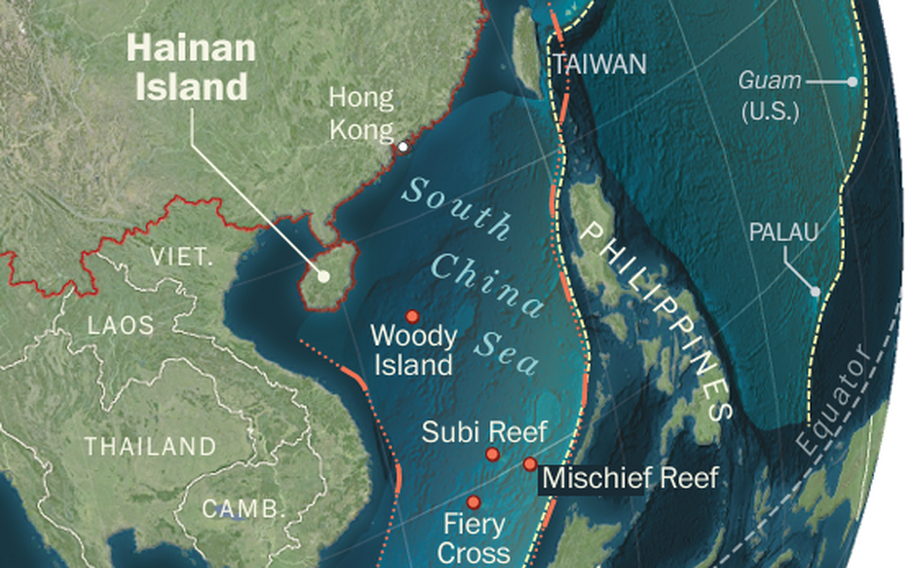

A map of the South China Sea region created by The Washington Post. (The Washington Post)

Hainan, a palm-fringed island known as China’s Hawaii, sits in the warm tropical waters of the South China Sea east of Vietnam.

It’s a popular tourist destination with soft-sand beaches, quaint mountain villages and fancy seaside resorts.

But just 500 feet from the lush grounds of the Holiday Inn Resort Yalong Bay is East Yulin Naval Base, home to Chinese destroyers and nuclear-armed submarines.

In the past decade, this island roughly the size of Taiwan has become home to China’s most concentrated buildup of modern military power and the launching point for its aggressive forays into the contested waters of the South China Sea.

Welcome to Hainan.

China has spent tens of billions of dollars turning farm fields and commercial seaports into military complexes to project power across thousands of miles of ocean it claims as its own.

The military buildup has a variety of motives, experts say: Beijing’s quest for global power. Protection of sea routes that fuel China’s economy. Resource exploitation. And the ability to defeat the United States and its allies if they try to thwart a Chinese attack on Taiwan.

Over two decades, the People’s Liberation Army has more than tripled the value of its military infrastructure on Hainan and on reclaimed reefs in the South China Sea, according to an exclusive analysis of some 200 military sites by the Long Term Strategy Group (LTSG), a defense consultancy commissioned by the Defense Department that was authorized to share its analysis of open-source data with The Washington Post.

Overall, the value of the military infrastructure on Hainan and in the South China Sea exceeded $50 billion as of 2022, according to the researchers. That’s more than the value of all U.S. military facilities in Hawaii, LTSG said.

The infrastructure at Greater Yulin Naval Base on Hainan was valued in 2022 at more than $18 billion, which rivals the value of one of the U.S. military’s most vital Pacific Ocean installations: Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, the researchers said. (That figure does not include the underground submarine pen carved out of a mountain on the East Yulin base.)

Hainan, China’s southernmost province, now boasts a military support apparatus - buttressed by staggering infrastructure investments in the South China Sea — that analysts say could, if present trends continue, neutralize what has long been considered a U.S. military advantage in a possible head-to-head conflict.

“It’s a profound challenge to the region. It’s a profound challenge to our allies and partners,” Adm. Samuel Paparo, commander of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, said in an interview. “There’s no denying that the increase in the capability within the South China Sea ... is a threat ... to U.S. interests.”

Senior U.S. military officials do not think Chinese leader Xi Jinping is ready to mount an attack that would draw in American forces. But that doesn’t mean the day won’t come — perhaps sooner rather than later.

“China is working very hard at having superiorities there that nobody else can match,” said retired Rear Adm. Michael Studeman, former commander of the Office of Naval Intelligence. “They’ve built an ability to project power with multiple types of capabilities — air, missile, militia, ships, submarines,” he said. “And we need to build up our capability and military posture with allies to forestall a Chinese attack.”

China’s staggering military buildup

The Greater Yulin Naval Base is the epicenter of the Chinese naval presence in the South China Sea, split across two deepwater bays and featuring the two most expensive military infrastructure items in the region today: an aircraft carrier dry dock and a carrier pier, together worth about $2.5 billion, according to LTSG estimates.

East Yulin Naval Base houses China’s only ballistic-missile submarine base — a premier facility that provides part of the nation’s strategic nuclear deterrent. Just south of a complex of six piers is a large cave built into a hillside that is designed to house multiple submarines deep underground and out of sight of surveillance satellites. Farther south is a degaussing facility that reduces PLA Navy vessels’ magnetic signatures, making them less detectable to anti-submarine aircraft and helping protect from mines.

The base also houses multiple weapons storage depots, with more under construction, and the entire naval complex is defended by anti-ship and surface-to-air missile batteries.

But Hainan’s military development isn’t limited to the high seas.

Two decades ago, a U.S. EP-3 reconnaissance plane was hit by a Chinese fighter jet and made an emergency landing at Hainan’s Lingshui Air Base — then a single narrow runway, dotted with Soviet-era jets and flanked by palm trees. Today, with modernization, that base is estimated to be worth $1.65 billion, and it boasts anti-submarine warfare aircraft, airborne early warning craft and a new munitions storage area. It is now one of three major military airfields on the island.

In addition, some 125 miles up the coast to the northeast lies the PLA’s Wenchang space launch facility, which China touts as its “portal to space in the 21st century.” The military launches satellites from Wenchang for communications, reconnaissance and surveillance purposes. With an inaugural launch in 2016, Wenchang is China’s only spaceport on a coast — the three others are in remote regions such as Inner Mongolia and Shanxi province.

Wenchang’s position closer to the equator gives rockets a performance boost gained from the Earth’s rotational speed. China’s latest, largest space modules can be launched only from Wenchang, and the spaceport aims to send astronauts to the moon by 2030.

Hainan also boasts a PLA Rocket Force base, one of more than 40 such facilities across the country. Built in 2019, the base houses DF-21D anti-ship ballistic missiles, according to Decker Eveleth, a specialist on Chinese nuclear and missile programs at CNA, a think tank based in Arlington, Virginia. Known as “carrier killers,” these conventionally armed weapons can travel more than 900 miles, enabling the PLA to conduct precision strikes against ships as far away as the western Pacific, Eveleth said.

Just last month, the Rocket Force launched from a site north of Wenchang an intercontinental ballistic missile with a dummy warhead that flew some 7,400 miles before landing in the South Pacific — the first such launch by China in more than 40 years.

The Hainan air bases provide cover for China’s fleet of ships, said Thomas Shugart, an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security and former Navy submarine warfare officer. They are part of what is known as a layered military posture: While the PLA navy roams the South China Sea, submarines can interdict enemy forces and conduct reconnaissance ahead of the fleet. Fighter jets provide air support and ward off advance threats, while missiles from the Rocket Force provide long-range cover.

“It is a comprehensive set of infrastructure that covers every domain of conflict on, over and under the South China Sea,” Shugart said. “And all this will be very hard to neutralize, especially during a major conflict over the Taiwan Strait.”

The new flash point

Hainan and the South China Sea lie in the southern reaches of what is sometimes called the First Island Chain, an area that arcs south from the Japanese archipelago, along the coasts of Taiwan and the northern Philippines, and then curves up along Malaysia and Brunei on the island of Borneo and north to Vietnam, in a giant fishhook pattern.

Much of this geographical boundary overlaps with China’s “10-Dash Line,” or the margins of what it claims as its maritime dominion. A long-standing PLA objective is to achieve the capability of “breakout” power projection along its entire maritime flank, from the Sea of Japan (or East Sea) down through the South China Sea, Studeman said. Beijing believes that the only way to protect its strategic lifelines, secure offshore resources and keep enemies at bay is to establish effective control inside much of the area demarcated by the First Island Chain, he said. That would be the first step in a strategic playbook to extend its power into the broader Pacific and the Indian and Arctic oceans, he said.

“China’s fever for domination in its near-abroad has become the most destabilizing trend in the Indo-Pacific,” he said.

The seas off China are some of the busiest shipping lanes in the world, a maritime highway for goods and energy.

In the past 10 years, China has built up island outposts in the South China Sea to extend its reach and assert dominance over these trade routes.

Democratic allies and partners of the United States — including the Philippines, Taiwan and Japan — lie along the First Island Chain and contest China’s militarization of the waters.

Farther east in the Pacific, along the Second Island Chain, lie major U.S. military bases. China’s militarized outposts are designed to restrict the ability of the United States and its allies to enter Beijing’s claimed zone of influence.

Some $7.4 trillion in trade flows through the waters of the South China Sea and the East China Sea each year — at least as of 2019, before the global pandemic disrupted supply chains — according to a 2023 Duke University report led by scholar Lincoln Pratson. Most of the fuel and other resources that China needs come from the Middle East and Africa through these seas — as does about 80 percent of its trade.

“If you have a conflict there, up to 30 percent of world trade in oil would be affected,” Pratson said.

The hottest flash point in the South China Sea of late has been near the Philippines, where Chinese coast guard vessels in June clashed with Philippine navy boats trying to resupply a rusted warship anchored at Second Thomas Shoal — an outpost in the Spratly Islands that both countries claim. The fracas became an international incident, prompting outrage from the Philippines and pledges by the United States that it would back its treaty ally if events escalated.

In August, coast guard ships from China and the Philippines twice collided near Sabina Shoal, another disputed area in the Spratly Islands.

If the clashes escalated into a shooting war, and the United States came to the Philippines’ defense, the nearest U.S. air bases are Andersen Air Force Base on Guam — a U.S. territory some 1,900 miles from Second Thomas Shoal — and Kadena Air Base on the island of Okinawa in Japan, 1,400 miles away.

Hainan, by contrast, is 800 miles away.

But just 18 nautical miles away is Mischief Reef, where China has an air base valued at more than $3.5 billion, according to LTSG.

Over the past decade, China has conducted a massive buildup of military installations across the South China Sea, from the Paracel to the Spratly Islands, including turning uninhabited atolls into islands bristling with military assets. An international tribunal in 2016 found the buildup illegal. LTSG pegged the value of these Chinese bases in 2022 at $15 billion, surpassing the value of all U.S. military infrastructure on Guam.

“There’s a reason why China can be so aggressive in the Philippines,” Shugart said. “In any level of conflict China has with the Philippines and with the United States, we would really have to ramp it up in a very significant way.”

Paparo, the top commander of U.S. forces in the Indo-Pacific region, noted China’s respectable arsenal. “There’s no denying the quantity of capability that [China] has put on Hainan island,” Paparo said, running through a list that includes six nuclear-powered ballistic-missile submarines, a destroyer flotilla, two fighter regiments, a ballistic-missile brigade, two attack submarine squadrons, two airfields, two naval bases, a coastal defense brigade and a combined arms brigade.

Though the United States, with ships and aircraft in the Pacific, is always ready to defend its allies and interests if China attacks, Paparo said, more must be done. “We have got to step up our investment in the defense industrial base and in our defense infrastructure,” he said, “in order to deter conflict with credible, decisive combat power.”

About this story: To estimate the dollar value of PLA infrastructure, LTSG categorized and measured each structure at some 200 sites through the use of satellite imagery. It applied a standard Defense Department metric called “plant replacement value,” which approximates the cost to replace a structure in 2023 dollars. All figures are set to U.S. national average prices, enabling comparisons between U.S. and Chinese infrastructure over time.

Aaron Schaffer and Kevin Schaul in Washington, D.C. and Pei-Lin Wi in Taipei contributed to this report.