Asia-Pacific

US, Japan to unveil first steps toward enhanced military alliance

The Washington Post July 27, 2024

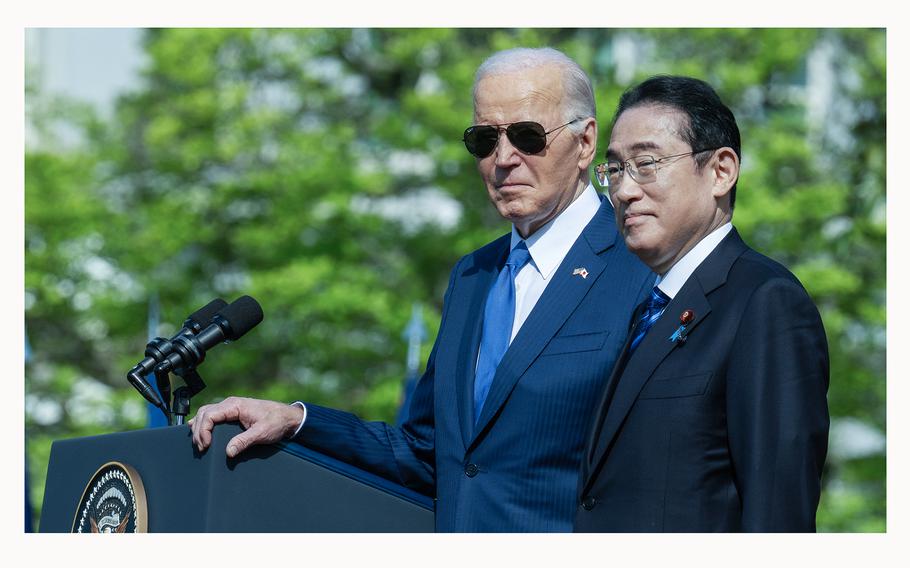

President Joe Biden stands beside Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida on the South Lawn of the White House on April 10, 2024. (Craig Hudson for The Washington Post)

Washington and Tokyo are set to announce Sunday the first concrete steps to modernize the command of their respective armed forces in Japan, a milestone toward a more robust military partnership.

The deepening strategic alliance comes as the two allies are increasingly concerned by the linked threats facing Europe and Asia, with China and North Korea fueling Russia’s war in Ukraine — and the fear that Moscow’s defiance of the west could embolden Beijing to invade Taiwan.

Japan has recently embraced a leadership role in the region, loosening traditional military constraints and beefing up its defense capabilities, both to shield itself and help the United States maintain stability in the western Pacific. It has announced a plan to set up a joint operational command by next March to better coordinate its sailors, airmen, soldiers and marines.

To align with Japan’s new command, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin on Sunday is expected to announce an upgrade of the current U.S. Forces Japan headquarters, which is largely an administrative office, to an all-service or “Joint Force” headquarters led by a three-star commander.

“It is really historic as it relates to the alliance and our military ties to Japan,” said a senior defense official, who like other U.S. and Japanese officials spoke on the condition of anonymity because the announcement has not yet been made.

Austin and Secretary of State Antony Blinken will be in Tokyo this weekend to meet with their counterparts, Defense Minister Minoru Kihara and Foreign Minister Yoko Kamikawa, respectively. The officials will advance agreements — including increased co-production of weapons and greater defense industrial cooperation — reached between Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and President Biden at the state visit in Washington this April.

The deepening defense relationship is part of the Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific strategy that seeks a counterweight to rising Chinese aggression by strengthening relationships with like-minded countries.

“This is a strategy predicated on building collective capacity with allies and partners, encouraging them to step up in innovative ways,” said Mira Rapp-Hooper, White House senior director for East Asia, at a discussion at the American Enterprise Institute this week, citing Japan’s partnership with the United States as a prime example of the strategy.

The upgrading of U.S. Forces Japan, based at Yokota Air Force Base outside Tokyo, is aimed at giving it powers similar to Japan’s new joint operational command. Unlike U.S. Forces Korea, where a four-star U.S. commander oversees both South Korean and American troops, the U.S. Joint Force headquarters in Japan will remain in charge of only U.S. forces, though the goal is for “our two militaries to operate together seamlessly,” the defense official said.

Under the plan, put forth by the head of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, Adm. Samuel Paparo, the commander of U.S. Forces Japan will eventually have increased authorities and staff to expand operational cooperation with Japan’s new joint command.

“It’s the eventual transformation of the U.S.-Japan relationship into a true military partnership,” said Christopher Johnstone, Japan chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and a former White House director for East Asia.

Details of the modernized command are still to be worked out, said defense officials, who noted they are doing so in consultation with Tokyo and Capitol Hill. Follow-on working groups will address questions such as the command’s area of responsibility and operational authorities.

“The fact of the matter is the Japanese see that China is not their only problem — they also have North Korea and Russia on their flanks,” said retired Rear Adm. Michael Studeman, former commander of the Office of Naval Intelligence. “It’s very clear that they have a multination problem, with the biggest bully being China. That’s the reason they’re trying to strengthen the alliance.”

The tighter the integration between the allies, the faster and more efficiently they can react in a crisis, say, in the Taiwan strait, experts said. Japan has also agreed to allow U.S. Marines to repurpose a regiment based in Okinawa so it can more rapidly disperse to fight in austere, remote islands.

Japan’s drive to modernize its military command structure comes alongside a commitment to surge long-stagnant defense spending and a new national security strategy that calls for long-range strike capability that could reach targets in mainland China. It’s a remarkable transformation of a country that for decades was constrained by postwar pacifist sentiment.

U.S. and Japanese officials will discuss co-production of certain weapons, in particular air defenses such as Patriot missiles that are badly needed in Ukraine. Future co-production projects may also include medium-range air-to-air missiles, officials said.

Japan’s strict defense export guidelines prohibit transfer of lethal arms to countries at war. But recent revisions enable it to sell arms built under U.S. license to the United States, according to Japanese officials. Washington would then be able to pass along similar weapons to an ally, U.S. officials said.

With air defenses in Ukraine in short supply, Japan has agreed to sell the United States 10 Patriot interceptors to restock its inventory, U.S. officials said. Washington had hoped for dozens more interceptors, but that effort fell through due to incompatibility with U.S. stocks, the officials said.

A trilateral meeting of the defense ministers of the United States, Japan and South Korea will also take place in Tokyo this weekend. It will mark the first trip a South Korean defense minister has made to Japan in 15 years, a sign of the rapprochement between Seoul and Tokyo, which have managed over the last year to set aside decades of animosity rooted in Japan’s harsh 35-year occupation of the Korean Peninsula. The leaders of the two Asian states and Biden met at a historic summit at Camp David last August, and they signed a formal “commitment to consult,” meaning that they would treat a security threat to one as a threat to all.

At the end of the trilateral, the defense ministers will sign a new framework of cooperation that sets up a regular calendar of ministerial meetings that will rotate among the three capitals, an annual trilateral exercise known as Freedom Edge (the first one was held this summer), and real-time missile threat warnings among the three partners.

Blinken also will join his counterparts from South Korea, India and Australia in Tokyo this weekend for a meeting of the “Quad” foreign ministers to discuss shared security, economic and other concerns.

All this activity — upgrading the military alliance, building diplomatic bonds — has “clearly caught China’s attention,” U.S. Ambassador to Japan Rahm Emanuel said. And that’s “exactly the party you want to see it.”

During their meetings this weekend, U.S. and Japanese officials are expected to discuss for the first time at the ministerial level Washington’s commitment to defend Japan in case of an attack, including the potential use of nuclear weapons, Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun reported.

“As the security environment around our country becomes more severe, it is extremely meaningful to discuss bilateral cooperation among ministers to strengthen U.S. extended deterrence,” Kamikawa said in a news conference this week.

Officials in Washington and Tokyo said that they expect advances in the alliance to endure no matter the outcome of November’s U.S. presidential election.

“It is our view that most of what we have done in the Indo-Pacific is and will continue to be bipartisan in its support,” a senior administration official said.

“We won’t change our course,” a senior Japanese official said. “If you objectively, cool-headedly assess the benefits that this cooperation brings the two countries, you have to conclude that this cooperation will definitely continue.”

Lee reported from Seoul. Julia Mio Inuma in Tokyo contributed to this report.