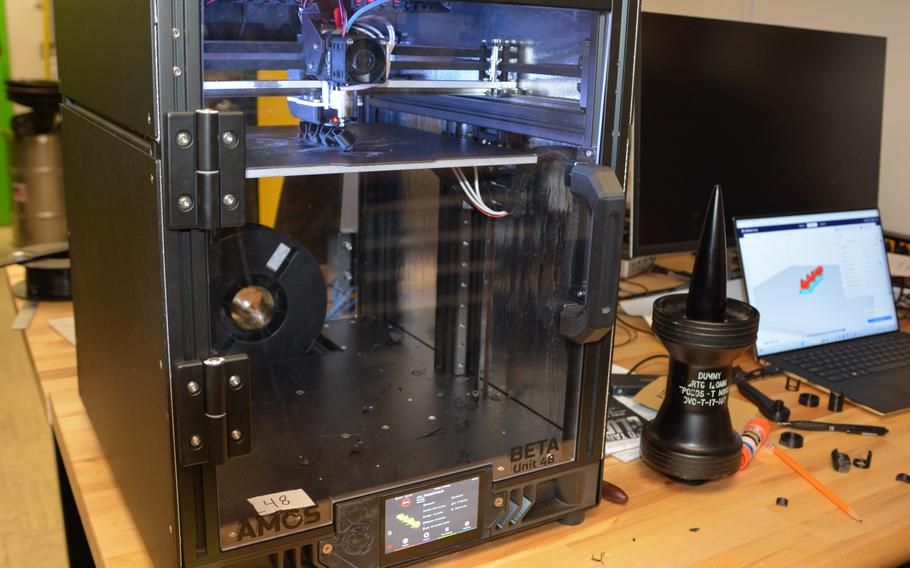

Navy Lt. Joel Hunter shows reporters a 3D printer being used in the Rim of the Pacific exercise to manufacture metal parts during a demonstration at Marine Corps Base Hawaii on July 2, 2024. (Wyatt Olson/Stars and Stripes)

MARINE CORPS BASE HAWAII — The Navy is experimenting with deployed 3D printing during the Rim of the Pacific exercise in pursuit of eventually shortening the supply line for crucially needed parts to mere hours.

Media were invited Tuesday to Marine Corps Base Hawaii for an up-close look at several 3D printers that manufacture parts made of metal and polymer.

“I don’t really think there’s been something like this done yet with the [Department of Defense],” Patrick Tucker told a group of journalists standing near a shipping container holding a 3D metal printer.

Tucker is a contractor working with the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif., which is carrying out the 3D experimentation during this summer’s RIMPAC. The Naval Information Warfare Center Pacific, based in San Diego, is overseeing the testing, Tucker said.

RIMPAC, taking place through Aug. 2 around Hawaii, is touted as the world’s largest international series of naval drills. This year, 29 participating nations brought 40 ships, 150 aircraft, three submarines, 14 land-based armed forces and 25,000 personnel.

The 3D experiment takes a “cradle-to-grave” approach in supplying needed parts during the exercise, Tucker said.

The “readiness problem” is identified, designs for a part are either found or reengineered from scratch, a prototype is made using the speedier polymer printer and then the final part is made with a metal printer, he said. Machinists complete the part fabrication by milling, drilling or grinding as needed.

A 3D printer, roughly the size of a minifridge, fabricates a part made of polymer at Marine Corps Base Hawaii on July 2, 2024. (Wyatt Olson/Stars and Stripes)

Two types of metal printers are being used during the exercise. One essentially employs liquid metals that are sprayed in layer after layer to create a part. It can fabricate parts in aluminum, nickel, bronze and stainless steel.

Another printer uses solid metal and melts it using a laser in fashioning the part.

The latter printer, along with a few polymer printers, are set to be loaded Monday aboard the USS Somerset, an amphibious transport dock that is participating in RIMPAC.

Widespread use of deployed 3D printing would be a way overcoming the “tyranny of distance” in the Indo-Pacific in the pursuit of getting needed maritime and aviation parts quickly, Tucker said.

“With the traditional manufacturing, the industrial base has gotten to where the responsiveness on some things is not appropriate to the readiness need,” he said. “So, we can augment that problem or reduce that problem through printing where we’re located.”

The industrial base that supports weapons systems is not thoroughly robust, he said.

“In some areas it’s very healthy, and other areas it’s very weak,” he said. “Sometimes where it’s very weak is actually some of the more important weapons systems that we have, and so [3D printing] basically reduces that negative effect.”

Marine Corps Gunnery Sgt. Mark Cureo displays a polymer camera mount used on a drone that was manufactured using a 3D printer as part of an experimental phase during the Rim of the Pacific exercise at Marine Corps Base Hawaii on July 2, 2024. (Wyatt Olson/Stars and Stripes)

All the services are involved in the experimentation to some degree. They are printing parts for the Coast Guard, Navy and Marine Corps.

Machinists with the 25th Infantry Division at Schofield Barracks will be aboard the Somerset when the 3D printer is hoisted aboard on Monday, Tucker said.

The Air Force is providing the services of its machine shop on Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam.

The metal 3D printer can produce a part weighing up to roughly 80 pounds. Metal printing a part takes four to 10 hours, although a large part can take some hours longer.

That is a short wait compared to the time it takes for some parts to arrive from manufacturers, Navy Lt. Joel Hunter, a student at the Naval Postgraduate School, said as he showed reporters aluminum-bronze piping that had been printed as part of the experimentation.

“There are parts that take up to 200 days to get where they’re needed,” he said.

Tucker said that in the future each ship could perhaps maintain its own 3D printer to avoid “reach back” to the continental U.S. to obtain a needed part.