In the northern Philippines, residents are skeptical of pushing China away. (Lisa Marie David/Bloomberg)

U.S.-Philippines ties are as strong as they’ve been in decades, with soldiers from both sides just wrapping up three weeks of joint military exercises that resemble the kind of preparations necessary to help repel a Chinese invasion of Taiwan.

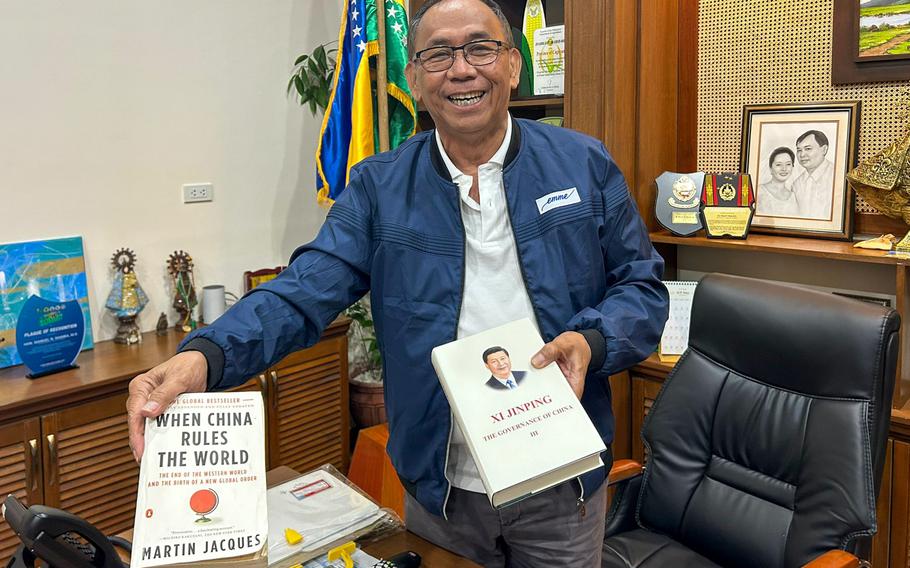

Yet in the northern Philippines, near a military base the U.S. recently won access to that is crucial to any defense of Taiwan, Beijing has made inroads with key politicians. Manuel Mamba, governor of Cagayan province, has traveled to China twice in the past 12 months and has four copies of President Xi Jinping’s book The Governance of China.

“We were VIPS, treated very, very well,” Mamba said of his visits to China. “We stayed in five-star hotels. We were free to roam around all over, even at night.”

Governor Manuel Mamba. (Peter Martin/Bloomberg)

In an interview at his office during the military exercises, he said he wasn’t “pro-China” even though he’s been a vocal critic of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s move last year to give the U.S. access to four more military facilities under the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement, popularly referred to as EDCA, including two in his province.

“They treat you well if you treat them well — if you go against them, like is happening now, they will not treat you well,” Mamba said about China. “The problem now is bullying. Remove the EDCA sites, there will be no more bullying.”

Strengthened U.S.-Philippines ties have generated optimism in Washington, where policymakers hope the Southeast Asian nation will become a reliable part of its defense strategy alongside Japan, South Korea and Australia. Beneath the surface, though, Washington and Beijing remain locked in a struggle for influence that is still playing out.

While the U.S. has made gains in recent years, Beijing isn’t giving up. Former President Rodrigo Duterte was deeply skeptical toward the U.S. and shifted the Philippines closer to China, and politicians like Mamba are worried the nation will be dragged into a war.

“The U.S.-Philippine relationship is the best it’s ever been, but there are questions over whether that can last,” said Brian Harding, a former Pentagon official who is now a Southeast Asia expert at the United States Institute for Peace. “Marcos needs to show that his pro-U.S. push can actually pay off economically for the Philippines.”

For now, the U.S. has a lot going for it: Just 10% of Philippine citizens said they favor a partnership with China, according to a survey conducted by Pulse Asia Research Inc. in December, while 79% said they favored cooperation with the U.S.

Pro-U.S. sentiment has risen in recent years as the Philippines and China have clashed over a series of contested reefs and islands in the South China Sea. Those tensions have pushed many Philippine politicians, including Marcos, closer to America.

“President Marcos is not pro-U.S. and he’s not anti-China — he’s pro-Filipino,” Defense Secretary Gilberto Teodoro Jr. said in an interview. “It just so happens that the major challenge to our rights is China.”

A Chinese restaurant near the naval base in Santa Ana, Cagayan in May. (Lisa Marie David/Bloomberg)

That tighter relationship has been most evident on the military side. The joint drills, which concluded Friday, saw more than 10,000 troops practice cyber warfare, live artillery fire and repel an amphibious assault on a beach. They culminated with the two nations bombarding a decommissioned, Chinese-made oil tanker, sending it to the bottom of the sea.

The decades-old Balikatan, or “shoulder-to-shoulder,” exercises have increasingly come to resemble real combat. They’re just one part of what U.S. officials describe as a historic shift in an alliance that helps safeguard a crucial shipping lane in the South China Sea and whose strategic location could prove decisive in a future war over Taiwan.

But U.S. officials acknowledge that shoring up the U.S.-Philippine alliance in the long run will require Washington to deliver economic benefits, not just military exercises. During a recent visit, U.S. Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo unveiled $1 billion in investments by American firms.

In the northern Philippines, residents are skeptical of pushing China away.

“The Philippines makes a lot of money from the Chinese people,” said Evangeline Raguindin, a teacher at the Taribubu Elementary School, where a Chinese foundation is paying for new school buildings. Asked about Manila’s recent territorial clashes with Beijing in the South China Sea, she said, “We’re not affected here.”

Mamba has results to show for his relationships in Beijing. This year, a new $73 million irrigation project began pumping water near his hometown of Tuao. Mamba had pursued the project for years and, when funding finally arrived, it came in the form of a loan from China Exim Bank.

Farmers praised the project, completed by China CAMC Engineering Company Ltd. Mamba described it as “a dream come true” that will “put a lot of money in the pockets of my neighbors.”

While in Beijing, Mamba said, he held a 1.5-hour meeting with Vice Foreign Minister Sun Weidong. The Chinese official warned him of the consequences of hosting U.S. troops and told him to urge Marcos to resolve the dispute in the South China Sea on a bilateral basis. Upon returning to the Philippines, Mamba said he wrote Marcos a letter making that point.

“The last thing that he said is, ‘Although we are neighbors and we are friends, if you will allow the enemies of China to stay with you, we will be forced to also engage you,’” Mamba said of Sun.

Asked about Mamba’s trip and whether China views the U.S. as an enemy, officials at China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded that the U.S. is “triggering tensions in the region and jeopardizing regional peace and stability. The Philippine side should recognize the situation clearly and should not sacrifice its own security interests for the sake of others, thereby jeopardizing its own interests.”

But analysts say their courting of leaders like Mamba isn’t a surprise.

“China is good at courting sub-national elites, promising them things from education opportunities to infrastructure,” said Julio Amador, CEO of Amador Research Services, a political consultancy in Manila. “These are not necessarily bad in themselves, but it shows that China understands that all politics are local.”

Mamba could be a short-term bet for China at this point. The governor is appealing an election commission ruling making him ineligible to run for office again and ordering his ouster over accusations that he misused public funds. But China’s roots go deeper than a provincial governor.

In 2018, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi opened a consulate in the Duterte family’s political stronghold of Davao, where numerous Chinese cities have also established sister city agreements in recent years. China also maintains a consulate in Laoag, a city of just 110,000 people in a country of 115 million, that’s also the political home of the Marcos family. In 2009, then-Congressman Ferdinand Marcos Jr. told U.S. officials that he had lobbied China to open the consulate, according to cables published by Wikileaks.

Although Marcos turned more pro-US after taking office, Duterte has continued advocating for China since leaving the presidency.

“I do not think that America will die for us,” Duterte said in an April 12 interview with the Global Times, an outlet affiliated with China’s Communist Party. “I would tell the Americans, you have so many ships, so you do not need my island as a launching pad.”

A Philippine official, who asked not to be identified discussing sensitive issues, said the country benefits from competition between the two powers, pointing out that Duterte’s pivot to Beijing helped get Washington to court Manila more aggressively. In the early months of his presidency, Marcos welcomed top officials including Vice President Kamala Harris, Secretary of State Antony Blinken, and Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin to the Philippines.

The official added that China still has a lot to offer the Philippines when it comes to economic ties, pointing out that — in the absence of US alternatives — Chinese firms are still the most attractive option when it comes to processing the country’s large and mostly untapped nickel reserves.

Vice President Sara Duterte, the former president’s daughter, offers one potential route to rapprochement with China. Despite serving as Marcos’s vice president, she has largely refrained from publicly commenting on Manila’s territorial disputes with Beijing.

“From her pronouncements, she’s definitely not pro-America,” Jose Manuel Romualdez, the Philippine ambassador in Washington, said in an interview. “Very often she says lines that are similar to her father’s in terms of how they feel about China.”

For Romualdez, the Philippines is just doing what it needs to do to stand up for itself.

“You have to choose between two bullies, and you choose the better one that would be your friend rather than one that would make you subservient to them,” he said. “If the United States is the bigger bully, then we’ll bring in the bigger bully to go after the bully in town.”

--With assistance from Manolo Serapio Jr, Dan Murtaugh, Philip Glamann, Yuki Tanaka and Josh Xiao.