A mass grave for 12 victims of the My Lai Massacre near Quang Ngai, Vietnam. (Wikimedia Commons)

Early on March 16, 1968, U.S. soldiers descended on hamlets in a coastal province of South Vietnam on a search-and-destroy mission that within a few hours left hundreds of infants, children and other civilians dead.

Some, huddled in groups, were shot execution-style.

Americans only learned of the atrocity well over a year later from news reports, but the full extent of the episode was not known until the Army’s Peers Commission published findings of an exhaustive inquiry in the spring of 1970.

Twenty-six soldiers were charged with crimes in the massacre, but only platoon leader Lt. William Calley Jr. was convicted after being found guilty of murdering 22 villagers. His life sentence was later commuted to 42 months.

The Peers inquiry, which mainly probed the extent Army officials covered up the killings, concluded that lack of leadership above all else was the main cause of the massacre, retired Army officers Paul Berg and Robert Rielly wrote in the 2021 book “High Ground: The Profession and Ethic in Large-Scale Combat Operations.”

“The report cited that leaders failed to follow policies, did not enforce policies, failed to control the situation, failed to check, failed to conduct an investigation, and did not follow up,” they wrote.

A new hypothesis

But the atrocity’s roots lead most clearly to the task force commander who concocted the mission, historian Marshall Poe argues in “The Reality of the My Lai Massacre and the Myth of the Vietnam War” published late last year.

Poe contends that the massacre would have likely never happened if not for Lt. Col. Frank Barker, the ambitious officer who planned the mission and longed for a battalion command.

Barker’s role has been largely overlooked because he was killed in a helicopter crash only a few months after the massacre; he thus faced no court-martial nor could he offer testimony in the subsequent investigation.

“Barker was a highly decorated officer who’d been in the Army for a long time, and he was well respected,” Poe told Stars and Stripes by phone March 4. “His actions on the day are really pretty much inexplicable, outside my hypothesis that he was really hoping the [Viet Cong] were in this village and he was going to get a big victory with a big body count.”

Poe, who taught history at Harvard and Columbia universities and is founder of New Books Network, pored over nearly 25,000 pages of documents, including hundreds of transcripts generated by the Peers inquiry.

Poe contends that Barker essentially ordered the troops to kill everyone in the hamlet designated by the Army as My Lai (4).

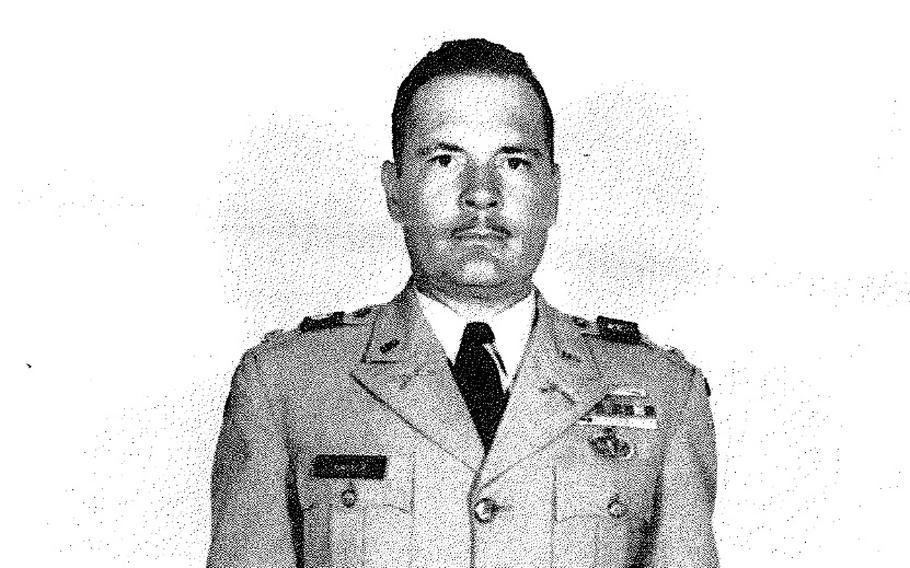

A historian contends that the My Lai Massacre would have likely never happened if not for Lt. Col. Frank Barker, the ambitious officer who planned the mission and longed for a battalion command. (U.S. Army)

Stepping-stone to promotion

Barker had fought in the Korean War and served as a military adviser during his first tour in South Vietnam.

After briefly commanding a battalion in 1967, he was transferred to a desk job. The following year, he was given command of a “battalion-sized task force” composed of units drawn from the 11th Brigade.

Poe contends that Barker viewed this task force as a stepping-stone to commanding a full-size battalion and further promotion.

Among the personnel in what came to be called Task Force Barker were Calley and his company commander, Capt. Ernest Medina. The men of Medina’s Company C killed most of the victims in the massacre, with Calley’s First Platoon “far and away most culpable,” Poe writes.

Barker’s task force had twice in February 1968 conducted operations in the Son My area — dubbed Pinkville by the U.S. military — in a hunt for members of the beleaguered 48th Viet Cong Local Force Battalion.

His plan to return to the area a third time, however, was based on dubious intelligence as to the location of the 48th and a mistaken notion about the presence of innocent civilians.

Army investigators were never able to definitively track down the flawed intelligence’s source.

Capt. Eugene Kotouc, the task force intelligence officer, offered conflicting stories as to the origin of the intelligence, but during one interview he told investigators it came from Barker.

Barker had also apparently come to believe that no civilians would be in My Lai (4) at 8 a.m. because at that time each day all Vietnamese farm peasants go to market at main villages — an assumption that Army investigators, who themselves had tours in Vietnam under their belts, regarded as ludicrous.

‘Extreme orders’

Barker’s superiors apparently had no clear idea about the operation he had planned.

Brig. Gen. Andy Lipscomb, commander of the 11th Brigade, told investigators he had no recollection of it.

Some officers told investigators that Barker had been explicit that he wanted My Lai decimated, with Kotouc and Medina saying he wanted everything burned and all the livestock killed.

In pre-operation briefings Medina gave to Company C, he “repeated and even amped up Barker’s already extreme orders,” Poe writes.

Numerous Company C soldiers testified they understood from Medina that everyone in My Lai was either Viet Cong or Viet Cong sympathizers.

“A dozen of Medina’s men state unequivocally that he ordered the entire population of My Lai (4) killed,” Poe writes.

For all the flawed assumptions underlying the March 16 operation — and the atrocity it would lead to — Barker could have stopped it even as it began to unfold and no Viet Cong returned fire.

What troops found was “a village full of old men, women and children,” Poe told Stars and Stripes. “Now, that’s where the operation should have stopped, right there.”

“The people who did this — that is, the soldiers on the ground — were incredibly badly led,” he said. “I mean, truly mind-bogglingly badly led by Barker, by Medina, and by Calley and others.

“Had responsible people followed the regs and done what they were supposed to have been doing … the operation would have been stopped almost immediately,” Poe said. “It probably never would have happened.”