A cook stove stands out on a charred landscape in a neighborhood destroyed by a wildfire in Lahaina, Hawaii, August 17, 2023. (Glenn Fawcett/Customs and Border Patrol)

More than four months since the deadliest wildfire in modern American history burned Lahaina to the ground, nearly 6,200 people are still looking for a place to live while their beloved Maui town is rebuilt.

There’s the retiree who has been shuttled from one shelter to another; the family of five who can only afford to stay in their overpriced, unlicensed rental until month’s end, when their shrinking finances will force them to leave the island; and the dozens of people camping on the beach to demand long-term housing for survivors of the blaze.

In the fire’s immediate aftermath, many predicted this crisis. And yet, despite the warning signs, Maui has hurtled headlong into a housing emergency.

At the height of the holiday season, thousands are still desperate for permanence, stuck in 33 hotels, according to the American Red Cross. Hundreds more are crammed in with family and friends or are stretching their budgets and burning their savings on sought-after temporary rentals. One analysis from the Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement estimates at least 1,000 people - out of a pre-fire Lahaina population of 13,000 - have already left the island.

“This is the saddest Christmas we’ll ever have,” said Amy Chadwick, a Lahaina resident for 25 years who will soon move with her husband, mother, two kids and three dogs to Satellite Beach, Fla., where the insurance payout from their destroyed home will last longer. “We are the first phase of a mass exodus. If something doesn’t change, thousands and thousands of people are going to leave.”

In the months since the August wildfire, local, state and federal government agencies have been scrambling for solutions to the escalating short- and long-term problems. But in the eyes of many residents, they have failed to move swiftly enough. Officials initially expected owners of the island’s many vacation properties to willingly rent out their homes to fire survivors at discounted rates, but instead market costs exploded and evacuees soon found themselves priced out.

Now, the state and county are offering robust incentives to cajole the owners of lucrative short-term rentals into offering long-term leases to the displaced. If this strategy fails, leaders have said they would temporarily ban the vacation properties to effectively force owners to house those who lost their homes.

The acute housing shortage has been exacerbated in recent weeks after tourism resumed in West Maui, with visitors spending top dollar to enjoy the holidays on Maui flocking back to resorts and beaches mere miles from the charred and cherished town. Officials decided to reopen the western part of the island in October, hoping that an influx of tourists would help jump-start the wrecked economy. Residents have fiercely criticized the move, accusing their governments of putting sightseers ahead of locals.

Even the hotel shelter program, which officials acknowledge is imperfect, is set to expire in February. It could be extended, a Red Cross spokesperson said, but that decision has not yet been made.

“We’re doing all we can to help people heal,” Hawaii Gov. Josh Green (D) said in an interview. “This is something that Hawaii has never experienced before, nothing of this magnitude.”

‘In constant survival mode’

For Chadwick’s family, little has been certain since the August blaze burned their home.

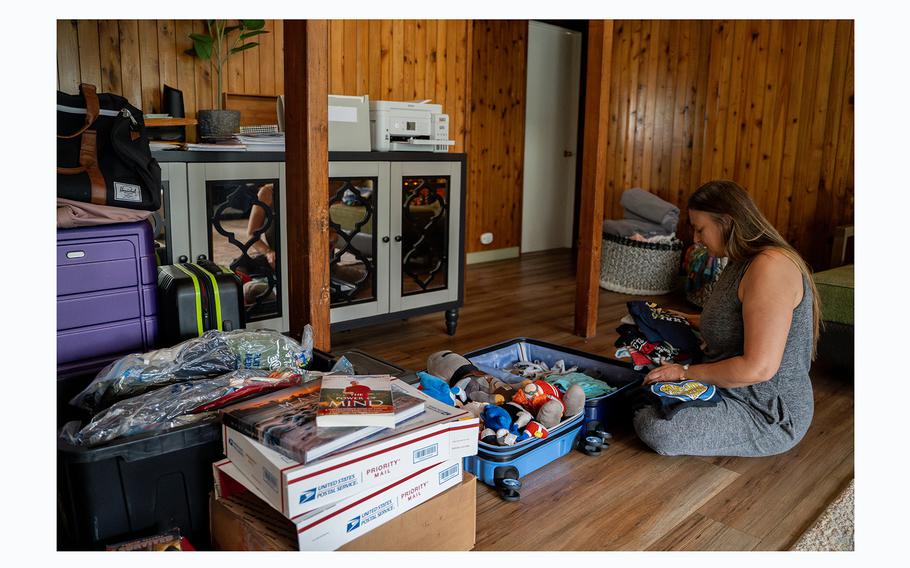

Amy Chadwick packs her son's T-shirts and toys at her temporary home in Lahaina. Chadwick and her family of five with three dogs are moving to Florida at the end of December after losing their home in August's wildfire. (Mengshin Lin for The Washington Post.)

First, they stayed with a friend, cramming 10 people into about 1,000 square feet. Then, the family moved to a small backyard unit before relocating again to a resort hotel, where pets were prohibited and they had to sneak their dogs in and out.

They were exhausted. They needed something stable, a place where their traumatized children could regain a semblance of normalcy. After a frantic search, Chadwick finally found a three bedroom West Maui house - for $7,000 a month. With no other options, the family moved in.

Chadwick later discovered the property was operating as an unlicensed short-term rental, and they couldn’t find anything long-term that they could afford. They began considering the unthinkable.

“I want to start living a life instead of being in constant survival mode,” said Chadwick, whose husband has lived in Lahaina for nearly all his life. “We have to make a decision, so we have to leave our island home. It’s heartbreaking.”

At the many Maui hotels doubling as shelters, the situation has been just as dire.

While the accommodations are upscale, they’re restrictive - many don’t allow pets or home cooking. They’re not set up for the long haul. The Red Cross manages the shelter program, which has come under increased scrutiny recently after several hotels ended their contracts, freeing up space for tourists and forcing evacuees to relocate to new facilities.

Some wildfire survivors have been moved upward of eight times, experiences they describe as destabilizing and painful. Sanford Hill, a 72-year-old retiree, was moved the day before Thanksgiving, from one hotel room to another.

“It’s hard for anybody to imagine what we’re still going through, especially at this time of the year,” said Hill, who lived in the low-income senior living complex Hale Mahaolu Eono, which was destroyed in the fire. “Eight of the people I celebrated Thanksgiving with last year are dead.”

Hill’s new hotel is under renovation and the drumbeat of construction keeps him on edge. The hotel-to-hotel shuffling, he said, has left him feeling less important than visitors.

“They want to get back to normal and start making money - it’s just so insulting to us,” Hill said. “You need to take care of the survivors before you take care of the tourists.”

When Alfy Basurto, his wife and five kids were staying in the hotels, they fell into a routine: Wake up, check Craigslist, then Facebook Marketplace, then Zillow, looking for rentals they could afford before heading to appointments with the Red Cross and the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Basurto went from running three small businesses, which burned in the fire, to signing up for unemployment.

Their old four-bedroom rental, now reduced to rubble, cost them $4,500 a month. Following the fire, the only one they could find big enough to fit the family charged $9,300. Basurto and his wife are trying to make it work, piecing together, among other sources, $1,000 each from unemployment, $1,200 from the survivors’ fund set up by Oprah Winfrey and actor Dwayne Johnson and another $4,000 through a state program.

They don’t know how long they can keep it up, but even the tenuous sense of security has brought relief.

“Being in the hotels is so poisonous to your mental health, you have no idea until you step out of it,” Basurto said. “You’re in a home and you start to feel like, ‘Oh, maybe I can rebuild my life.’ You start to have hope. Everything changes.”

Since the move, he has begun documenting the struggle of others, who have been herded from hotel to hotel, unable to find permanent housing.

One local grassroots organization, known as Lahaina Strong, has been occupying a popular resort beach for more than a month, demanding faster government action and helping families - many of whom lost vehicles in the fire - move from one hotel to another.

Jordan Ruidas, one of the organizers with Lahaina Strong, with her children, La'iku, left, and Waiaulia. (Mengshin Lin for The Washington Post)

Lahaina Strong’s row of two dozen tents has become a source of badly-needed solidarity and resources, said organizer Jordan Ruidas, but there is only so much the group can do.

“They need houses, they need homes,” Ruidas said. “It’s something we, the community, can’t give to them and that’s what breaks our heart. We started hubs to provide people water, diapers and food, but we cannot provide the homes for them. That’s where we need the government to step in.”

‘A shared sacrifice’

The island’s housing crisis built on problems that predated the fires.

Hawaii is the state with the highest cost of living, and Maui County is one of the country’s most rent-burdened places. Historically, more than half of the renters there have spent at least 30 percent of their income on housing. The situation prompted the governor to declare a state of emergency in July, one month before nearly 3,000 buildings, many of them homes, were reduced to ashes.

The issue is not the number of units left on the island, but that Maui is the most extreme example of a statewide dynamic: A large share of the island’s housing stock - more than 20,000 dwellings - is devoted to short-term vacation rentals or second homes, a chunk of which sit empty for much of the year.

The imbalance between available homes for year-round residents and vacation properties, which cater to visitors and bring the county immense tax revenue, is the biggest hurdle to addressing Maui’s housing crunch, experts and officials say.

“At this point, it’s almost like money can’t even help this problem,” said Matt Jachowski, a Maui-raised and Stanford-trained computer scientist who built a website to help match displaced families with vacant housing. “The only thing that will help this problem is the units that the short-term and second homeowners are sitting on. No amount of money is going to build housing fast enough.”

Lately, local leaders have taken on a sharper tone when addressing these property owners, the vast majority of whom do not live on Maui.

At a recent emergency meeting of the county council, Maui Mayor Richard Bissen said everyone in the community must make “a shared sacrifice” to help the island recover. For short-term rental owners, he said, that means leasing to fire evacuees - not tourists.

One concern “is that they will be losing money,” Bissen said. “The answer to that is: That’s right. They will be losing money. But what they will be gaining is much more, and what the whole community gains.”

Bissen recently unveiled an incentive proposal to encourage the transition, with a carrot and a stick: Every short-term rental owner who leases to a survivor for at least one year will be exempt from property taxes; anyone who refuses to do so could face a future tax hike.

In conjunction with the county plan, the governor’s office has offered to pay “competitive rates” on behalf of displaced families to short-term owners, who often rent their properties to vacationers for far higher sums than they could demand on the long-term housing market.

“Not only is it the right thing to do morally, it is also financially a very fair option because people are going to be kept whole,” Green said. “We have to restore balance if we’re going to take care of our people here.”

If these incentives don’t generate enough housing, both leaders have said they would support a moratorium on vacation rentals until all evacuees have a place to live - a step Green calls “the nuclear option,” which would have been hard to fathom before the fires.

“It’s almost impossible to change statewide housing policy in the moment,” he said. “But I will do it under emergency rules if that’s what it takes.”

Other potential solutions, like the construction of tiny home villages, have faced delays.

“I agree with our community that our government isn’t moving with the sense of urgency that this situation calls for - not just the county, but the state and federal government as well,” said Keani Rawlins-Fernandez, a Maui County council member.

State Sen. Angus McKelvey holds a piece of melted aluminum, a remnant of his car that burned during the August wildfire in Lahaina. McKelvey also lost his home in the blaze and has been living in hotel shelters since. (Mengshin Lin for The Washington Post.)

State Sen. Angus McKelvey (D), who represents West Maui in Hawaii’s legislature, is both a fire survivor - his home burned down and he’s been living in hotel shelters since - and an elected leader charged with charting the path forward. He said Green and Bissen should have acted sooner, and he plans to push for more sweeping measures in the upcoming legislative session.

“You have to be draconian for the greater good,” McKelvey said.

The executives have defended their approach, saying an outright ban on rentals could prompt legal action that would further delay recovery.

“We’ve considered all of these for a while,” Bissen said in an interview. “But each one is a little more drastic than the one before, because we can face potential lawsuits for each of these decisions, and if we can avoid that and still get housing, that would be ideal.”

It remains unclear whether short-term rental owners will embrace the county and state programs. Unlike many vacation property owners, Colleen Medeiros lives on Maui and is Native Hawaiian. One of her two rental properties has been in her family for generations. She supports the incentives and plans to participate in them, but she said a full-blown moratorium could be ruinous for people like her, who earn a living off their properties.

“It is false to assume that all owners are ultrawealthy and don’t actually need an income from their second properties,” said Medeiros, who has two kids in college, a third enrolling next year and multiple mortgages. “I can’t just give up the income I was bringing in. I have to adjust my whole life first, all my finances, and that just doesn’t happen overnight.”

Priced out of paradise

For some, it’s already too late.

Chadwick and her husband, who ran businesses that made environmentally-friendly sunscreen and tanning lotion, also lost their company warehouse to the fire. The short-term rental conversion plan might have helped the family stay on the island, she said, if it had happened sooner. But instead, they have signed a lease for a house in a beach town on Florida’s Atlantic coast.

They wanted to move someplace small, laid-back, near the ocean. Somewhere like Lahaina.

Chadwick and her family hope to return, once their home - and their town - is rebuilt. But it could take years. For now, they’re savoring one last Christmas on the island, even though it looks entirely different from holidays past.

Every year around this time, the Chadwicks’ home would begin to resemble the Griswolds’ in “National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation,” decked out in lights and decorations. The kids, ages 12 and 9, burst with holiday spirit. This season, the family’s mood is somber. Their ornaments burned, and they can’t spare money for presents.

“I feel so bad for my children,” Chadwick said. “But we don’t want to pretend. We don’t want to put on a fake show for them. We want them to remember our blessings.”

She did buy a small, 3-foot tree. It will be standing in their pricey rental on Christmas Day, along with their packed suitcases.