Asia-Pacific

Emotional sketches made in Sugamo Prison find their way to former inmate’s family

Stars and Stripes November 29, 2023

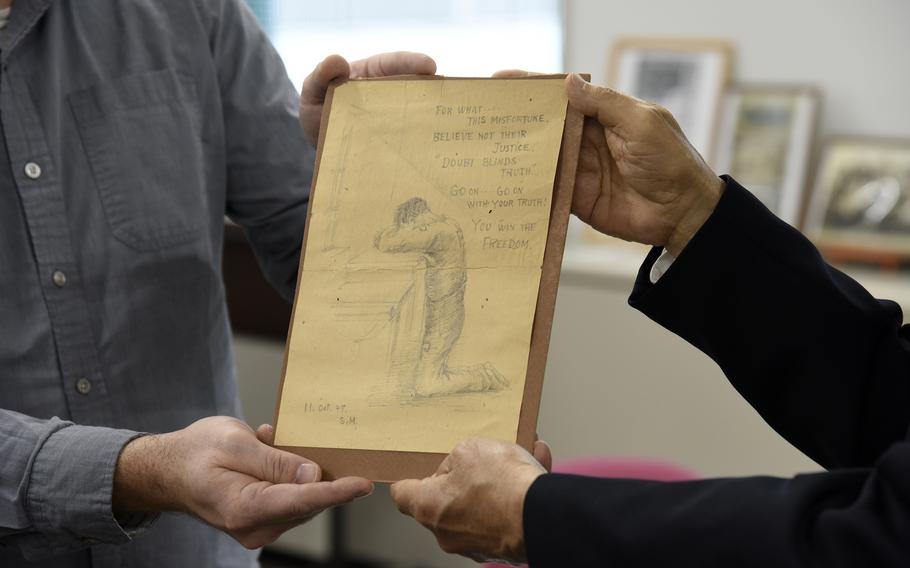

Philip Ackland, left, a Department of Defense Education Activity teacher at Yokosuka Naval Base, Japan, presents a sketch Shichiro Matake made at Sugamo Prison to the former inmate's son, Kiyoshi Matake, at Kurume University in Fukuoka, Japan, Nov. 24, 2023. (Jonathan Snyder/Stars and Stripes)

FUKUOKA, Japan — A series of prison sketches by a Japanese physician convicted, but later acquitted, of crimes against Americans during World War II were handed to the man’s family on Friday, thanks in part to two Yokosuka Naval Base employees.

The detailed drawings — about a dozen pencil sketches on yellowed parchment — depict the experiences of Shichiro Matake while he was incarcerated at Tokyo’s infamous Sugamo Prison in 1947 and 1948.

“Here I am!” he wrote in Japanese on a sketch of himself kneeling in his cell. “This is the first ward in the town of hell.”

Matake, who died in 1969 at age 61, was one of five doctors accused of cannibalism following a series of gruesome experiments on American prisoners of war that took place at Kyushu Imperial University in 1945, said Philip Ackland, an engineering teacher at Yokosuka’s Nile C. Kinnick High School.

Matake and the others were accused of removing and eating a U.S. airman’s liver after a vivisection, Ackland told Stars and Stripes during an interview at his home on Nov. 19.

All five doctors were later acquitted; Matake, for the rest of his life, maintained his innocence and said he was pressured to make a false confession.

‘Where’s the justice?’

On Friday, Ackland and friend Kazuya Matsunaga, a satellite technician at Yokosuka Middle School, returned the drawings to two of Matake’s children at Kurume University’s Fukuoka campus.

“We were never told by our parents about the drawings,” son Kiyoshi Matake told Stars and Stripes during the handover in Fukuoka. “It feels like a miracle.”

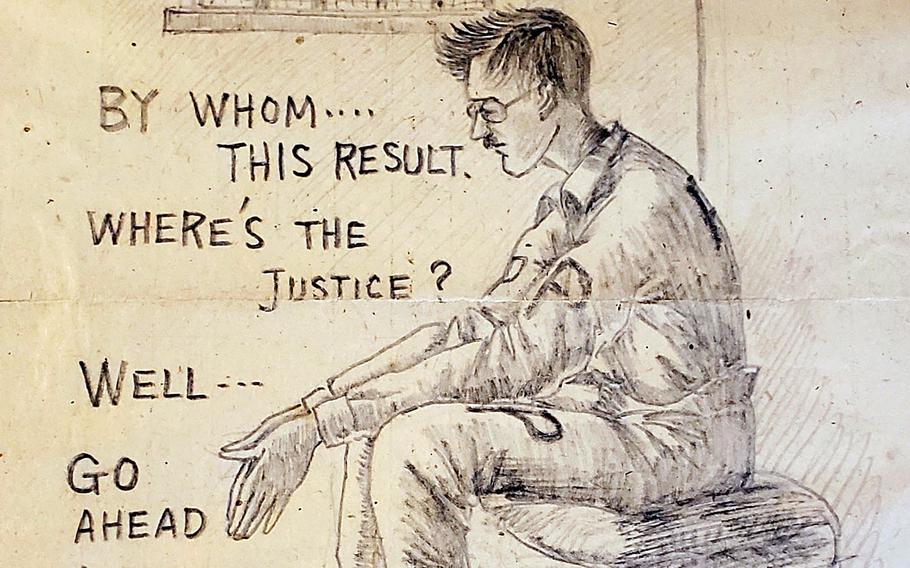

In one drawing, dated Oct. 9, 1947, Matake depicts himself seated barefoot in his cell. A caption written in English asks, “Where’s the justice?”

Another sketch shows him being processed and examined medically; others demonstrate a sense of humor that survived his imprisonment.

“Warning: pictures taken here are not good for arranged marriage purposes,” he wrote in Japanese on a sketch of his mugshot.

A photograph of a sketch drawn in Sugamo Prison by Shichiro Matake, a Japanese military doctor convicted, and later acquited, of war crimes against U.S. soldiers during World War II. (Alex Wilson/Stars and Stripes)

The Yokosuka pair became involved in the drawings last summer, when a family friend of Ackland, Sue Peterson, asked if he could help return them. Peterson is the daughter of Donald Faivre, a U.S. Army soldier who served as a guard at Sugamo Prison.

“[Shichiro Matake] drew the series of drawings and they came into Donald’s possession,” Ackland said. “The idea was that the prisoner was not able to actually send them to his family, so Donald said, ‘Oh, maybe I can do that for you.’”

Faivre ultimately was unable to do so, and after several years lost the Matake family’s address. Peterson and her siblings inherited the drawings when their father died in 2015 at age 87.

Realizing the connection between Matake and the Kyushu experiments, Matsunaga said it took only about a week to track down the family.

‘An instant bond’

The experiments involved eight captured U.S. airmen who were imprisoned after their B-29 bombers crashed in 1945, according to a research paper by Osaka City University associate professor Takashi Tsuchiya.

The Japanese army ordered them to be handed over to a team at Kyushu Imperial University where doctors conducted experiments on the live airmen, according to the paper. These included the removal of various organs and the use of seawater as an experimental replacement for saline solution.

“There were plenty of members there at the university that were definitely opposed to what was going on; they didn’t understand,” Ackland said. “So, not everyone was doing something knowingly wrong.”

Around 30 university doctors and military staff stood trial in 1948 for the experiments, with 23 convicted, according to a 2015 report from The Guardian.

Five, including Matake, were sentenced to death and another four to life imprisonment, but their sentences were reduced after the Korean War broke out in 1950; none of those sentenced to death were executed, according to Tsuchiya’s research paper.

At least one individual involved in the experiments said he was unsure whether he could have refused participation, citing “strong abhorrence” to U.S. soldiers in Japan at the time, according to a report in a March 2018 volume of Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University’s Journal of Asia Pacific Studies.

The Matake family will need time to consider what to do with the drawings, Kiyoshi Matake said.

“It was moving to see the mutual respect and admiration between the Matake and Faivre families,” Ackland said. “Despite a language barrier and being a world apart, these families shared an instant bond.”