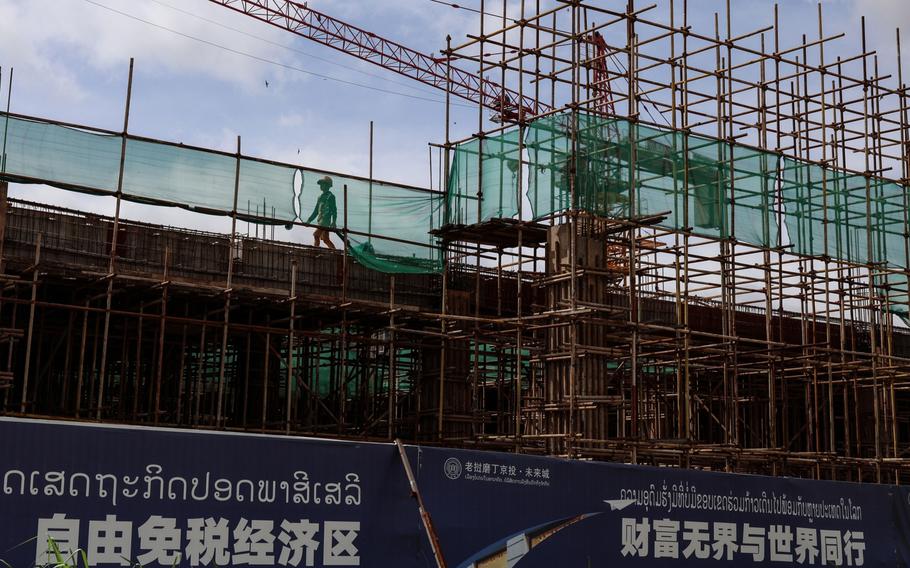

A worker on a scaffolding at a Belt and Road construction site near the China-Laos border in Boten, Laos. (Valeria Mongelli/Bloomberg)

When President Xi Jinping first assembled world leaders to map out his vision for expanding Chinese soft power via a web of infrastructure investment in 2017, he called the Belt and Road the “project of the century.”

As the Chinese statesman opens the third Belt and Road Forum this week, the future of his brainchild looks uncertain. While the project has drawn $1 trillion in its first decade, according to estimates from think tank Green Finance & Development Center, the momentum has tapered off in recent years.

China’s overall activity in BRI countries is down about 40% from its 2018 peak as the world’s second-biggest economy slows. Beijing faces accusations of being an irresponsible lender driving countries to default. Fractured ties with the U.S. have made association with Xi’s pet project increasingly divisive — Italy, its sole Group of Seven member, is set to exit by the year’s end.

One Chinese official considered the BRI dead, dealt twin blows by COVID and China’s economic problems. The official, who asked not to be identified discussing a sensitive topic, said the government hoped this summit to mark BRI’s 10th anniversary would reinvigorate the project.

The U.S. assesses that the BRI is in deep trouble, according to a senior American official who asked not to be identified to discuss private conversations. Beijing has less capital to lend and pressure is growing to recoup the outstanding money it loaned, the official said.

Xi will have the chance to answer his critics when a host of Global South leaders arrive this week to pledge support for the program and test Beijing’s bandwidth for new deals — chief among them Russian President Vladimir Putin. Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban, Indonesian President Joko Widodo, Argentina’s President Alberto Fernandez and Thai Premier Srettha Thavisin are also attending.

“Xi will invite his best friends and have all these people come together to celebrate,” said Alfred Wu, an associate professor at the National University of Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. “It’s a clear message that China is trying to have its own allies while challenging the U.S.-led world order.”

Pandemic pullback

The outbreak of COVID put the brakes on China’s infrastructure and trade initiative, as a global slowdown imperiled debtors’ ability to repay their loans. Zambia was the first African country to default during the pandemic in late 2020, putting China, the nation’s largest creditor, in the spotlight.

As other nations including Ethiopia, Sri Lanka and Pakistan fell into debt crises, annual engagement under the BRI plummeted to $63.7 billion in the first year of the global health crisis, according to a study by the Green Finance and Development Center at Shanghai-based Fudan University — down from a peak of more than $120 billion in 2018.

That pullback has been sustained by geopolitical tensions and domestic problems plaguing China’s economy, which show little sign of abating.

“External shocks like the Ukraine war and, perhaps in the coming weeks the new war in the Middle East, are deepening debt and inflation burdens,” said Michael Kugelman, director of the South Asia Institute at the Wilson Center.

China has responded by shifting to so-called “small but beautiful” projects that benefit people’s livelihoods. The state-run People’s Daily this month cited a water plant in Botswana upgraded by a Chinese firm and a technology partnership with a seed company in Costa Rica as examples.

The average BRI investment deal decreased by 48% from the 2018 peak to about $392 million in the first half of this year, according to the Fudan report. The report tracks both the value of construction projects that are funded by China as well as those that Chinese companies have equity stakes in.

China’s private companies are also becoming more active in a space once dominated by policy banks and state-owned companies, said Christoph Nedopil Wang, director of the Griffith Asia Institute, who authored the Fudan study.

That’s resulted in some big investments with a focus more on global markets than building infrastructure. China’s Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. and Mercedes-Benz Group AG, for example, plan to invest more than $7 billion in a plant in Hungary, the biggest single project in a BRI country since it started in 2013.

Yet the Belt and Road initiative has always been loosely defined, with the label often applied to any projects in nations with friendly ties to China.

The strategy’s geographical focus has also evolved in step with Xi’s foreign policy. Saudi Arabia was a top three recipient of BRI lending this year, according to the Fudan study, as the Chinese leader seeks to expand his influence in the Middle East.

Political problems

Still, Italy has questioned whether Xi’s flagship initiative brings economic benefits at all.

“We have exported a load of oranges to China, they have tripled their exports to Italy in three years,” Italy’s Defense Minister Guido Crosetto said in July. “Paris, without signing any treaties, in those days sold planes to Beijing for tens of billions.”

After Italy signed an agreement to cooperate on the BRI in 2019, its imports from China accelerated but that bump wasn’t reciprocated. Last year, Italian exports to China only rose 5%, lagging behind those of Germany and France — two countries that aren’t in the BRI.

Hungary’s Orban said after a meeting with Chinese Premier Li Qiang on Monday that his country is looking to boost cooperation with China. “Instead of blocs and shutting out, Hungary’s goal is to develop economic cooperation,” Orban said, adding that China is the biggest source of foreign direct investment this year.

China’s Foreign Ministry hasn’t announced plans for a leader’s roundtable that Xi hosted at the two previous events, as the summit looks set to attract a smaller crowd of world leaders.

Spurred spending

For Global South nations, Xi’s efforts to pitch his country as a leader of the developing world has been a vital source of funding. China extended $114 billion in development financing to Africa alone from 2013 to 2021, according to a study by Boston University.

That spending spurred the U.S. and European governments to expand engagement with some developing nations to counter China’s influence. But while Western rivals have pledged billions of dollars, many of their projects have been slow to get off the ground.

China’s credit lines will be tested this week when Kenya’s leader William Ruto is expected to ask for $1 billion to finance stalled infrastructure projects. Wu Peng, department director of African affairs at China’s Foreign Ministry, said this month a “big loan” for a new railway project in Africa will be announced soon.

That won’t be enough to reverse the overall trend of a downsized BRI, but may signal Xi’s ongoing commitment to the program as a linchpin of his foreign policy.

Even with the slower pace of investment, Xi’s imprint means BRI won’t fade away, according to Raffaello Pantucci, a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore.

“Xi being associated with it so closely, means it’s going to stay an important and relevant thing for as long as he stays in power,” Pantucci said. The pace was probably “too fast at the beginning anyway.”

With assistance from Chiara Albanese, Peter Martin, Tom Hancock, James Mayger and Zoltan Simon.