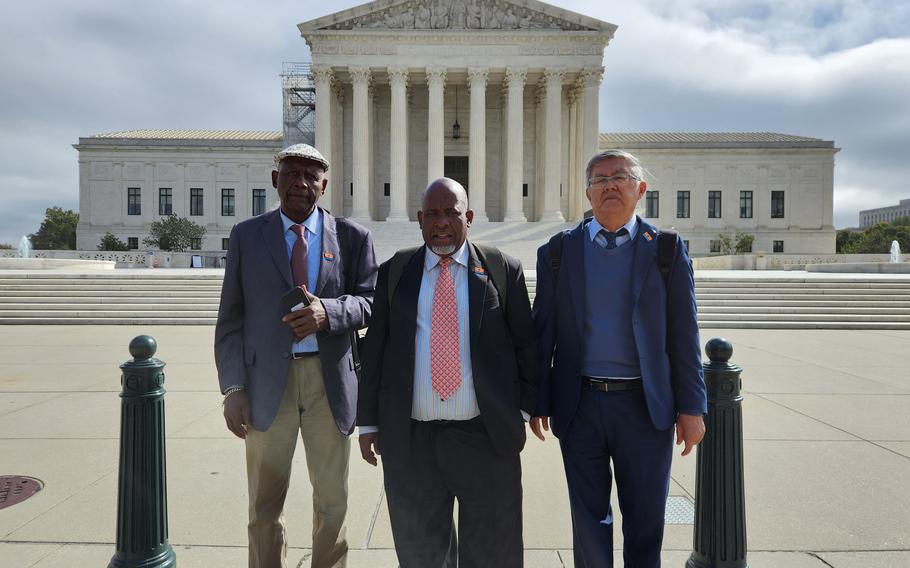

Olivier Bancoult, center, the leader of the Chagos Refugee Group, stands on Capitol Hill with Roger Alexis, a Chagossian, left, and Philip Ah-Chuen, a Mauritian advisor to the group. They met last week with lawmakers to demand reparations and an apology for the forced removal of thousands of Native inhabitants from the Chagos Islands in the 1960s and 1970s to make room for a U.S. military base. (David Vine/The Washington Post)

In the late 1960s, thousands of indigenous inhabitants of the Chagos Islands, an atoll in the Indian Ocean, were forced by the United States and the United Kingdom to leave their homeland to make room for construction of a U.S. military base.

For decades, the islands had been administered by the British colony of Mauritius. But in the early 1960s, the British government agreed to lease part of the colony to the United States to build a naval base, in the process separating the Chagos Islands from Mauritius to form a new British colony called the British Indian Ocean Territory.

According to court records, the U.S. government insisted that the Chagossians living there — a population descended from enslaved Africans brought by the French in the 1700s — be deported to make room for construction of the naval base.

In 1971, the commissioner of the British Indian Ocean Territory, Bruce Greatbatch, enacted an ordinance effectively banning native people of Chagos from the islands.

Chagossians would later testify before the International Court of Justice in The Hague that territorial agents threatened inhabitants who refused to leave. Then the British and U.S. agents began killing their dogs, according to court records and documents.

First, they tried to shoot the dogs with M16 rifles, according to a statement by the government of Mauritius filed in 2018 in the International Court of Justice. When that failed, they tried poisoning the dogs with strychnine. Finally, they used raw meat to lure the dogs into a shed, where they gassed the animals with exhaust from U.S. military vehicles.

For more than 50 years, Chagossians have argued that their rights have been violated. In 2004, they began filing for justice in international courts, arguing that the U.K. and U.S. governments violated their human rights by forcing them to leave home.

Last week, Olivier Bancoult, leader of the Chagos Refugee Group, flew to Washington to meet with members of Congress and demand that the U.S. government issue an apology and pay reparations for the forced removal. In 1968, Bancoult and his parents were among more than 1,800 Chagossians driven into exile.

“What we are hoping to have is an apology from the U.S. government, together with reparations,” Bancoult said during an interview on Capitol Hill. “We want to put the U.S. government in front of their responsibility.” During his visit, Bancoult attended a screening and discussion at American University of the 2022 documentary “Absolutely Must Go,” which chronicles the Chagossian fight to return home. Cristina Becker, associate director of Human Rights Watch’s U.S. program, said Bancoult’s visit helps expose the story of what happened to the Chagossians.

“We are reaching a point where current members of Congress and President Biden can no longer say that they aren’t aware of the crimes against humanity that the U.S. government continues to carry out against the Chagossian people,” Becker said. She called it “astounding” that the U.S. and U.K. governments “continually deny Chagossians access to cohabitate or even work on the U.S. base that displaced them, despite extending that permission to other civilians.”

The U.S. military base on the Chagossian island of Diego Garcia is one of the most strategically positioned U.S. military installations outside the United States because of its location in the Indian Ocean, said David Vine, professor of anthropology at American University and author of the book “Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia.”

Bancoult was 4 when his family was prohibited from returning to its home in Chagos after taking Bancoult’s sister to a hospital in Mauritius for treatment. His sister died, and the family was forced to make a new life in Mauritius.

For more than 40 years, Bancoult has fought for Chagossians to return to Chagos, arguing that they have never asked for the removal of the U.S. base, but just for an opportunity to live in their birthplace. According to a February Human Rights Watch report, “The U.K. government has repeatedly refused to allow the Chagossians to return, citing vague concerns about security and cost. The U.K. government has repeatedly acknowledged in the last 20 years that its treatment of the Chagossians was ‘shameful and wrong,’ but these apologies have not led to concrete reparations.”

“I think there is some discrimination taking place against the Chagossians,” Bancoult said. “All over the world, where we have a U.S. military base, we have habitation for local people. It’s the only place where we have a U.S. military base that local people did not get access to.”

Human Rights Watch wants the U.K. and U.S. governments to pay reparations to the people forced from their homeland and allow them an “unfettered permanent return.” It is also requesting an apology from King Charles III.

By 1973, the last of the native Chagossians were deported to Mauritius — which gained independence in 1968 — where many live in abject poverty. In 1982, a group of Chagossians began hunger strikes and protests, demanding their right to return home, according to Vine. The U.K. agreed to pay 4 million pounds in compensation. But individual Chagossians received only about $6,000 in total compensation from the British government, according to Vine. Some got nothing at all.

In February, a State Department spokesperson told The Washington Post, “The United States remains steadfast in its respect for and promotion of human rights and fundamental freedoms of individuals around the world and acknowledges the challenges faced by Chagossian communities. The manner in which Chagossians were removed is regrettable.”

In a February letter to Human Rights Watch, Zac Goldsmith, Britain’s minister of state for overseas territories, commonwealth and energy, wrote of the deportations, “The U.K. has made clear its deep regret about the manner in which this happened.”

In 1973, Goldsmith said, Britain paid the Mauritian government 650,000 pounds “to meet the cost of resettling those displaced from the islands.” Goldsmith said that over the years, the British government has conducted feasibility studies, ultimately deciding “against resettlement on the grounds of feasibility, defense and security interests and the cost to the British taxpayer.”

In 2000, Chagossians challenged their exile in the United Kingdom’s High Court. The British court ruled the expulsion was illegal. But the ban was reinstated, citing security concerns, and after much legal back and forth, it remains it place.

In 2010, the U.K. created the Chagos Marine Protected Area, one of the world’s largest reserves, which banned fishing — a main source of livelihood for Chagossians — and the collection of corals. That same year, WikiLeaks released a State Department cable revealing that U.K. and U.S. officials had agreed that creating that protected marine reserve around the islands would effectively prevent Chagossians from returning. “Establishing a marine reserve might . . . be the most effective long-term way to prevent any of the Chagos Islands’ former inhabitants or their descendants from resettling in the BIOT,” the cable said, according to WikiLeaks.

In 2017, Chagossians took their case to the International Court of Justice. Two years later, the court ruled that the creation of the British Indian Ocean Territory was “unlawful” and that Mauritius was the rightful sovereign of Chagos. The court called on the United Kingdom to “end its continued administration of the Chagos Archipelago as rapidly as possible.” The United Nations General Assembly responded by passing a resolution ordering the U.K. to cooperate with Mauritius in helping Chagossians return.

Last year, the U.K. government began negotiations with the Mauritian government over Chagos. But Chagossians say they have been excluded from the negotiations.

In Washington, Bancoult made his way to Capitol Hill. “It is a real urgent matter to deal with,” Bancoult said. “The U.S. is a country that is supposed to give a good example to other countries.”

“We have never asked for removal of the U.S. military base,” he said. “We say, let us live there. If anyone lives there, priority should be given to the Chagossians.”