Virus hunting — including efforts to collect genetic material from bats in pursuit of pathogens not known to infect humans — relies on three stages of work. A mishap at any stage would invite risk of an outbreak or a global pandemic, according to infectious-disease experts. (Aaron Steckelberg/The Washington Post)

In the summer of 2019, a mysterious accident occurred inside a government-run biomedical complex in north-central China, a facility that handles a pathogen notorious for its ability to pass easily from animals to humans.

There were no alarms or flashing lights to alert workers to the defect in a sanitation system that was supposed to kill germs in the vaccine plant's waste. When the system failed in late July that year, millions of airborne microbes began seeping invisibly from exhaust vents and drifting into nearby neighborhoods. Nearly a month passed before the problem was discovered and fixed, and four months before the public was informed. By then, at least 10,000 people had been exposed, with hundreds developing symptomatic illnesses, scientific studies later concluded.

The events occurred not in Wuhan, the city where the coronavirus pandemic began, but in another Chinese city, Lanzhou, 800 miles to the northwest. The leaking pathogens were bacteria that cause brucellosis, a common livestock disease that can lead to chronic illness or even death in humans if not treated. As the pandemic enters its fourth year, new details about the little-known Lanzhou incident offer a revealing glimpse into a much larger - and largely hidden - struggle with biosafety across China in late 2019, at the precise moment when both the brucellosis incident and the coronavirus outbreak were coming to light.

Multiple probes into both events by U.S. and international scientists and lawmakers are spotlighting what experts describe as China's vulnerability to serious lab accidents, exposing problems that allowed deadly pathogens to escape in the past and could well do so again, potentially triggering another pandemic.

Beijing has embarked on a major expansion of the country's biotechnology sector, pouring billions of dollars into constructing dozens of laboratories and encouraging cutting-edge - and sometimes controversial - research in fields including genetic engineering, and experimental vaccines and therapeutics. The expansion is part of a government-mandated effort to rival or surpass the scientific capabilities of the United States and other Western powers. Yet, safety practices in China's new labs have failed to keep pace, a Washington Post examination has found.

Lab accidents happen everywhere, including in the United States, where illnesses and deaths caused by accidental infections have occurred, especially before the adoption of modern safety standards in the 1970s. But Chinese government reports, bolstered by interviews and statements by Western and Chinese officials and scientists who visited the facilities as recently as 2020, describe ongoing equipment problems and inadequate safety training that in some cases resulted in lab animals being illegally sold after being used in experiments, and contaminated lab waste being flushed into sewers. The problems are exacerbated, experts say, by a secretive, top-down bureaucracy that sets demanding goals while reflexively covering up accidents and discouraging any public acknowledgment of shortcomings.

China adopted legislation to improve biosafety around the time of the covid-19 outbreak caused by the novel coronavirus. But the lack of transparency makes it difficult to assess how the new standards are being implemented. The country's recent history, which includes multiple documented instances of pathogen "leaks" or lab-related infections as well as a rushed entry into high-risk research with lethal viruses, provides ample reasons for concern, Western officials and experts say. Biosecurity expert Robert Hawley, who for years oversaw safety programs at the U.S. Army's maximum-containment lab at Fort Detrick, Md., expressed dismay over "imprudent" lab practices he observed in inspection reports obtained by a congressional oversight committee.

"It is very, very apparent that their biological safety training is minimal," Hawley said.

Multiple emailed requests seeking comment from the Chinese Embassy in Washington and China's National Health Commission did not receive a response. Beijing has accused U.S. officials of scapegoating China over the coronavirus pandemic, while also rejecting criticism of China's record on transparency and lab safety as hypocritical. U.S. agencies and institutions sometimes restrict access to scientific data, especially for defense-related research. In a 2020 State Department email obtained by the nonprofit organization U.S. Right to Know, a senior Trump administration official appeared to acknowledge that some criticism of China "called out actions that we ourselves are doing."

Whether lab safety was a factor in the coronavirus outbreak remains unclear. The World Health Organization and the U.S. intelligence community both continue to point to a possible lab accident as one of the two ways that the pandemic may have started. In an updated intelligence assessment revealed publicly in February, Energy Department analysts joined the FBI in concluding that a lab leak was the most likely cause, although some other U.S. agencies continued to side with scientists who think a natural spillover from infected animals - perhaps raccoon dogs, sold at a Wuhan market - is to blame. Advocates of both theories expressed only low or moderate confidence in their conclusions.

Chinese officials have rejected the lab-leak hypothesis while also stymying independent investigations into the pandemic's origins. For three years, Beijing has blocked access to information about the testing of humans and animals in the early weeks of the outbreak, and it also has refused to release a full inventory of the virus strains that were being studied at its top civilian and military virology labs.

What is clearer now is that conditions existed - and perhaps still exist - that raised the odds of an accidental outbreak. An expert group headed by Philip Zelikow, who was the executive director of the 9/11 Commission, is expected to highlight China's struggles with biosafety as part of a wide-ranging report probing the conditions that set the stage for the global pandemic. Zelikow said the problem of lagging standards and unsafe working conditions for Chinese scientists was exacerbated by "an environment of extraordinary political and economic pressure."

"Biosafety culture and practices struggled to keep up with racing biotech skills and ambitions," he wrote in an email.

Shiny new labs

Twenty years ago, a different coronavirus ignited China's ambition to become a biomedical superpower. The pathogen that causes the disease known as SARS, or severe acute respiratory syndrome, appeared out of nowhere in 2002, jumping from bats to a mongoose-like mammal known as the Asian palm civet and then to humans in China's southeastern Guangdong province. Eventually, SARS infected more than 8,000 people worldwide, most of them in China and Hong Kong. About 800 died.

To China's leaders, SARS exposed a vulnerability to zoonotic diseases - those that spread from animals to people. In the wake of SARS, Beijing vowed to rapidly modernize the country's biomedical institutions, which were seen as lagging because of what official media termed a Western "stranglehold" on biotechnology.

Those promises were mostly kept, with technical and financial assistance from Western countries. The 15 years following the SARS eruption witnessed an unprecedented surge in Chinese partnerships with U.S. and European scientific institutions as Beijing sought to address the country's serious health-care challenges while also narrowing the technology gap.

()

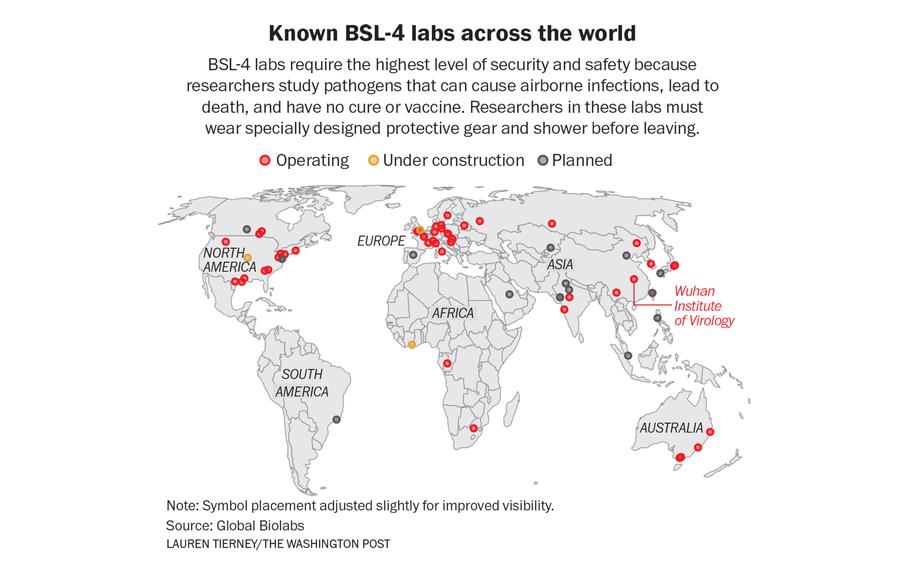

One of the most prominent collaborations was a U.S.-Chinese virology research project investigating coronaviruses, backed by millions of dollars in grants from the National Institutes of Health and involving China's top scientist in the field, the Wuhan Institute of Virology's Shi Zhengli, and counterparts from the New York-based nonprofit EcoHealth Alliance. Another collaboration was a Chinese-French agreement to construct China's first ultra-secure laboratory - known as a Biosafety Level 4, or BSL-4 facility - built to handle the deadliest known pathogens. That lab, operated by the Wuhan Institute of Virology, became fully operational in 2018. Since then, Beijing has quickly built at least two more BSL-4 labs, in the cities of Harbin and Kunming, and announced plans to construct dozens of BSL-3s - labs that handle second-tier threats such as the anthrax bacteria - to ensure that each of China's 34 provinces and autonomous regions has at least one - for a total of at least 120, according to a count by independent analysts.

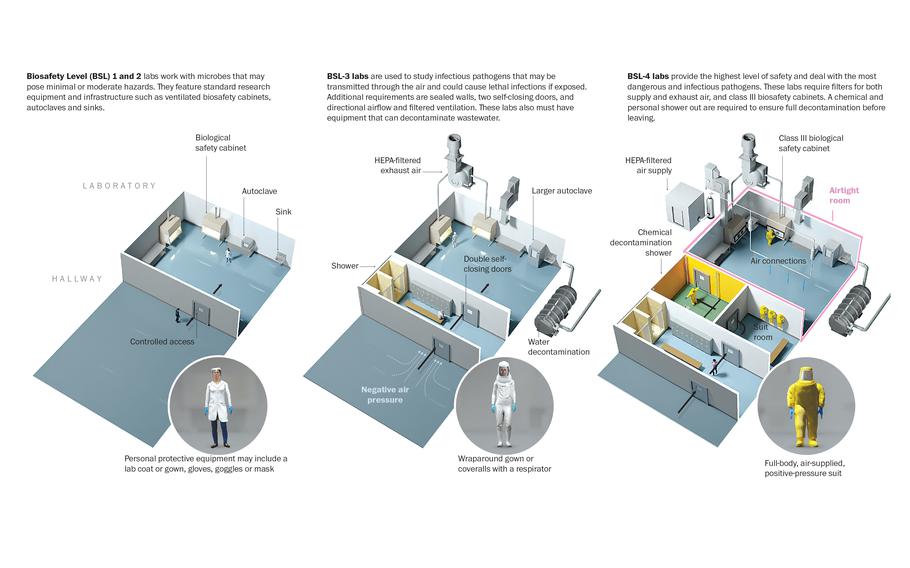

Biosafety Level (BSL) 1 and 2 labs work with microbes that may pose minimal or moderate hazards. They feature standard research equipment and infrastructure such as ventilated biosafety cabinets, autoclaves and sinks.

BSL-3 labs are used to study infectious pathogens that may be transmitted through the air and could cause lethal infections if exposed. Additional requirements are sealed walls, two self-closing doors, and directional airflow and filtered ventilation. These labs also must have equipment that can decontaminate wastewater.

BSL-4 labs provide the highest level of safety and deal with the most dangerous and infectious pathogens. These labs require filters for both supply and exhaust air, and class III biosafety cabinets. A chemical and personal shower out are required to ensure full decontamination before leaving.

Yet, for at least some labs, speed and ambition occasionally meant cutting corners.

Chinese officials said little publicly about a serious incident involving the SARS virus that occurred in 2004, when two lab workers in Beijing separately contracted the disease on the job and spread the illness to at least seven outsiders, one of whom died, WHO officials said. Meanwhile, as new labs were being built, the kinds of safety programs and rigorous training that developed over years in the top Western labs were slow to take hold, and in some cases were simply ignored, according to inspection documents and reports by Chinese scientists who visited or worked in the facilities.

The Washington Post reviewed official statements and reports, collected and translated by congressional researchers, State Department officials and independent investigators, that point to systemic failures in implementing safety standards necessary to prevent a spillover of dangerous bacteria and viruses. The deficiencies were being documented at a time of intense activity and rapid change. Across China, a sweeping, years-long effort was underway to collect and analyze thousands of previously unknown viruses harvested from wild animals across Asia. At the same time, Chinese labs were plunging headlong into the emerging field of synthetic biology, embracing new and controversial bioengineering techniques in which scientists tweak the genetic structure of viruses in an attempt to anticipate future evolutionary changes that could make the pathogens more dangerous to humans.

Yet, as Western countries discovered painfully years ago, running a successful laboratory requires more than just an ability to conduct experiments.

"It's not just about the guys in white coats. It's also about the people who run the systems," said Hawley, the former Army biosafety chief. "You can't cut corners. And you can't glean the knowledge that's required in a two-week course and then expect that people will be able to fly solo. It doesn't happen that way."

Flushed into sewers

In January 2020, as the first covid-19 cases were being investigated, Chinese news media reported a rare scandal involving one of the country's laboratories. A 58-year-old professor at an agricultural university was arrested and charged with illegally selling animals used in the lab's research program.

The Chinese authorities eventually sentenced the professor to 12 years in prison, a move apparently intended as a warning to others. The problem of off-the-books selling of lab animals was deemed to be of sufficient magnitude that China's government was compelled to adopt a law that year expressly forbidding Chinese labs to sell "animals used in experimentation."

Whether anyone became sick from exposure to laboratory animals is unknown. But the report amounted to an official acknowledgment of safety problems that are generally harder to spot and, in China's case, only rarely mentioned in public.

Lab inspection reports and other documents obtained by congressional investigators and independent researchers show Chinese labs struggling to implement safety standards, including at some of the country's newest and most prestigious institutions, such as the Wuhan BSL-4 lab. The essential conclusions also are echoed in confidential State Department cables drafted in 2018 after U.S. scientists visited the Wuhan facility and met with Chinese counterparts there. One cable noted a "serious shortage of appropriately trained technicians and investigators needed to safely operate this high-containment laboratory."

Although the Wuhan BSL-4 lab was built according to French designs, Chinese officials gradually shut out their French partners and replaced some of the costlier safety features with locally made equivalents that had never been put to the test under BSL-4 conditions, according to documents reviewed by The Post. For example, less than 18 months after the facility's official opening, lab managers issued short-notice bids and patent applications to fix apparent problems with doors seals, the air filtration system and monitoring devices that were supposed to alert scientists to possible leaks. The records were obtained as part of an ongoing oversight investigation by the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions and independent analysts with DRASTIC, a loose confederation of data analysts and amateur sleuths who mine open-source Chinese documents for information about covid-19. There is no known evidence suggesting that the BSL-4 facility was involved in research on the virus that causes covid-19; that research was taking place elsewhere at the Wuhan Institute.

Other documents describe a common litany of shortcomings at multiple facilities, including shortages of trained workers, inadequate or missing equipment, bad waste-management practices and generally sloppy conditions.

"There is a lot of debris in the laboratory," an unnamed Chinese inspector noted in October 2019 after a visit to a secure research facility at Wuhan University, which operates a BSL-3 lab a short distance from the Wuhan Institute of Virology's main campus. According to the inspection report, obtained by DRASTIC, lab conditions were "crowded and chaotic," with "experiment and living area . . . not separated" and "chemical waste and household waste mixed."

At the Wuhan Institute of Virology, social media postings in late 2019 confirm previously reported safety lapses among lab workers conducting field research on unknown coronaviruses. Chinese scientists collected 20,000 virus samples from bats and other animals by 2019 and conducted genetic tests for hundreds of them, documents show. Social media postings show scientists working in caves filled with thousands of disease-carrying bats and sometimes handling the creatures and their excrement without gloves or other protective gear needed to prevent accidental infection.

Back in the laboratory, unidentified viruses were grown in petri dishes and tested under BSL-2 conditions, rather than in more-restrictive BSL-3 conditions, as would be customary in the United States and Western Europe, according to U.S. scientists who collaborated with the institute's researchers. In a description of the research prepared for the Senate Health Committee, congressional researchers said that studies on previously unknown coronaviruses continued under "inappropriately low biosafety levels" until after the start of the coronavirus outbreak, and that the work included creating genetically modified "chimeras" by splicing genetic material from one virus onto another for lab tests. Wuhan Institute officials did not respond to a request for comment.

The problems were sufficiently worrisome that a few senior Chinese officials and scientists felt compelled to speak out. In a rare public acknowledgment, Gao Hucheng, a senior member of the government's National People's Congress, warned in a 2019 report to fellow legislators that the "biosecurity situation in our country is grim." He specifically cited the potentially grave consequences stemming from "laboratories that leak."

That same year, a second Chinese official acknowledged that his government had failed to adequately fund many of the high-containment labs it had built. Yuan Zhiming, a deputy director of the Wuhan Institute of Virology, said numerous high-level labs "have insufficient operational funds for routine, but vital, processes."

"Currently, most laboratories lack specialized biosafety managers and engineers," he wrote in 2019 in the Journal of Biosafety and Biosecurity. "This makes it difficult to identify and mitigate potential safety hazards in facility and equipment operation early enough."

But the most widely cited deficiencies have involved flaws in handling hazardous laboratory wastes, a problem cited in inspection reports and other internal reviews of lab practices in different parts of China. In a 2018 report, obtained by Senate Health Committee investigators, an official in China's southern Guangzhou region noted that "laboratory wastewater is being directly released" into sewage systems. The report described lab workers as careless in their handling of "highly dangerous" lab cultures, failing to properly clean up after experimenting with dangerous viruses and bacteria.

Similar problems were noted at Wuhan.

"Laboratories in China have paid insufficient attention to biological disposal," said Yang Zhanqui, the director of the pathogen biology department at Wuhan University, in comments carried in 2020 by China's Global Times, a publication closely aligned with the government. He cited a habit among researchers to "discharge laboratory materials into the sewer after experiments, without a specific biological disposal mechanism."

Whether any live pathogens were released was unclear, inspection reports said, in part because of a failure by the labs to adequately monitor for leaks. Without adequate monitoring, leaks can continue unnoticed for long periods - which is precisely what happened in Lanzhou in the summer of 2019.

An invisible cloud of bacteria

As Chinese investigators later determined, the Lanzhou crisis began with a problem so simple that it could be grasped by anyone who has ever shopped for groceries: a lapsed expiration date.

It happened inside the Lanzhou Biopharmaceutical Plant, a manufacturer of vaccines that occupies a warehouselike building in the center of Lanzhou, a provincial capital with nearly 4 million inhabitants about 960 miles southwest of Beijing. The plant, which is ringed by high-rise apartment complexes on the southern bank of the Yellow River, was set up for the production of vaccines to prevent brucellosis.

Vaccine production started with live bacteria in fermentation tanks, and by the end of the process, the pathogens were normally killed with the use of chemical disinfectants. But somehow, in July 2019, the plant began using a chemical that was well past its prime, according to Chinese media accounts and interviews with scientists who investigated the accident. The waste-treatment regimen was only partly working, allowing many of the bacteria cells to survive.

A scholarly account of the accident released nearly three years later, in June 2022, describes a large plume of bacteria seeping from the exhaust stacks and then drifting toward the apartment buildings and a nearby veterinary school.

"The waste gas contained the notoriously easy-to-aerosolize pathogen, which was then further carried by southeast winds," wrote Georgios Pappas, a Greek infectious-disease specialist and author of the report published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases. The result, Pappas said, was "possibly the largest laboratory accident in the history of infectious diseases."

With no warning about the accident, people living downwind never had a chance to protect themselves.

Over the following weeks, students in the nearby veterinary school began developing unexplained symptoms: achy joints, fever, unusual fatigue. Even lab mice in the school's research wing started becoming sick, and the females delivered stillborn babies. Local officials initially suspected an exposure from infected animals inside the school itself. But then residents in the nearby apartment complex began to fall ill.

One of them, a 39-year-old man who lived less than a block from the biopharmaceutical plant, told of how his health inexplicably deteriorated in the fall of 2019. "I suffered from severe back pain, sweating, sleepiness, and swelling," the man, who gave the name Li Xiao, told the state-run Chinese news site the Paper months after the government officially acknowledged the mishap. "I didn't know the reason at the time."

The first official hint of a larger problem came on Dec. 27, 2019 - four months after the leak was halted - in the form of a paper notice tacked to bulletin boards in local neighborhoods, advising residents to sign up for free testing for brucellosis, a disease almost unknown in urban centers such as Lanzhou.

In the following months, the testing zone had to be expanded multiple times as sufferers were found miles downwind from the plant. State-run media accounts eventually acknowledged the outbreak and pinned the blame on the vaccine facility - eight managers were subsequently fired, and the plant shut down - while initially claiming that only a handful of residents had actually gotten sick.

In reality, out of nearly 70,000 people tested, more than 10,000 were seropositive, meaning enough brucellosis-causing bacteria had entered their lungs to trigger their immune systems into producing antibodies, Pappas said, citing figures compiled by the provincial health authorities in Lanzhou's Gansu province.

How many symptomatic cases developed is unknown, but experts believe the number is in the hundreds. Some, like Lanzhou resident Li Xiao, were briefly hospitalized and then treated for months with different antibiotics. Nearly a year later, when interviewed by the Paper, he was still suffering from the effects of the disease, in addition to stomach pain from the drugs he was taking. After months of treatment, he said, he had decided to check out a local support group formed by neighbors whose experiences with brucellosis were similar to his.

"There are more than 400 people in this group," he said. "As far as I know, almost every household in our community has infected patients."

Chinese documents show that more than 3,000 people living near the plant applied for compensation, an indication of at least a mild illness, Pappas said. Three years after the events, the fact that more than 10,000 people were affected by the leak is "nowhere to be found in official data," he told The Post. "It is as if these patients never existed."

"This was a major event, with significant overtones, that nobody talked about," Pappas said, "while the officials responsible for releasing relevant information failed, and still fail, to do so."

Science hobbled by secrecy

Despite its scale, the Lanzhou accident barely made a blip in global media coverage. That's partly because of official suppression, as initial Chinese accounts depicted only a minor mishap and very few illnesses. But those reports also coincide with panic over a different disease that erupted in Wuhan, one of China's top biotechnology centers.

The first publicly recorded cases of covid-19 - then known only as a "pneumonia of unknown cause" in Chinese medical reports - occurred in December 2019, just before the brucellosis accident came to light. On Dec. 28, a day after Lanzhou residents were ordered to report for testing, medical investigators officially linked the Wuhan cases to a "novel coronavirus" that would be called SARS-CoV-2. Within a month, the virus had spread to cities throughout China, and then around the world.

Chinese officials initially refused even to acknowledge the problem at Wuhan and threatened punishment for any scientist or doctor who spoke out publicly. Epidemiologists believe the suppression campaign ultimately contributed to the rapid spread of the virus in the early weeks of the outbreak. It probably also hindered efforts to document precisely how and where the coronavirus emerged.

Chinese medical personnel who tried to sound the alarm in the early weeks of the pandemic were questioned by security officials and forced to confess publicly to "spreading rumors." When World Health Organization representatives launched a formal investigation of the outbreak in 2020, Chinese officials barred the release of key information, including raw results from human and animal tests during the weeks when the first cases were emerging, or the genetic sequences for the strains of coronaviruses that scientists there had collected and studied. Later, some of the WHO contingent acknowledged being pressured by their Chinese hosts to issue public statements dismissing the possibility of a lab leak, even though they lacked the data to determine how the outbreak originated.

"The Chinese government doesn't want to admit mistakes because it might challenge their image of being all-knowing and all-powerful," said Alina Chan, a molecular biologist at the MIT-Harvard University Broad Institute and a co-author of "Viral," a 2021 book that explores the events leading up to the pandemic. "And people on the ground are afraid of admitting mistakes because it could have very dire consequences for them."

Pappas, the Greek physician who investigated the bacteria leak at Lanzhou, said China's tendency toward concealment serves the country poorly. Not only does it impede efforts to fix real problems, he said, but it also fuels suspicions among outsiders of a coverup - even in cases where the suspicions are unwarranted.

"The paucity of information remains an issue for totalitarian regimes," Pappas said. "The delay in notification of the initial SARS outbreak, the critical lost days on informing about specific characteristics of SARS-CoV-2, the absence of info on the Lanzhou leak - all belong to a common narrative: the absence of data, aiming to create a false sense of absence of events."

The Washington Post's Cate Brown, Cate Cadell and Alice Crites contributed to this report.