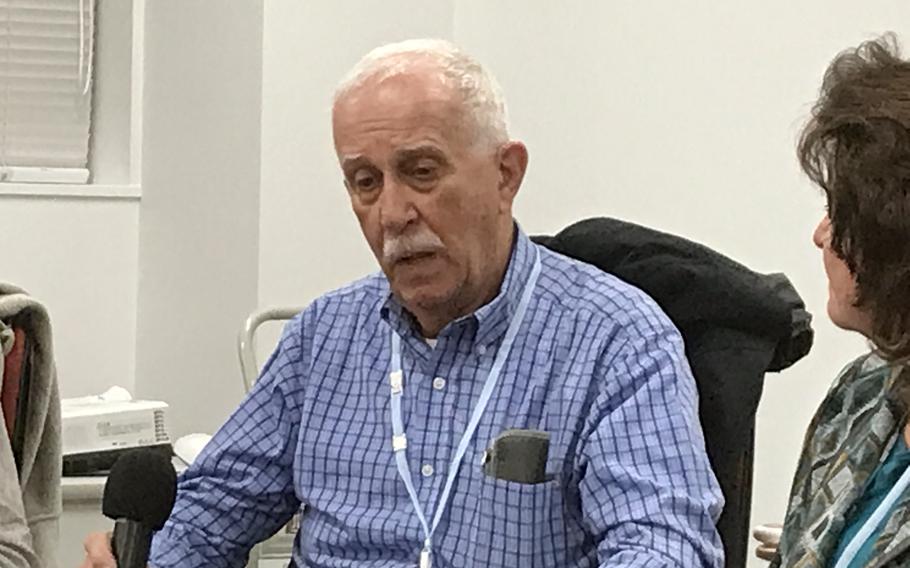

Thomas Hoskins Jr. speaks about his father's experiences in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps, during an event at Temple University, Japan Campus, in Tokyo, Tuesday, Feb. 14, 2023. (Seth Robson/Stars and Stripes)

TOKYO — This year, no former U.S. prisoners from World War II made an annual trip to the Japanese capital at the invitation of their former captors.

Instead, a son and six daughters came this week to relay how their parents survived forced marches, slave labor and brutal treatment by guards after being captured in the Philippines.

Yet none mentioned any grudges held by their parents, who all died decades later, toward the Japanese people.

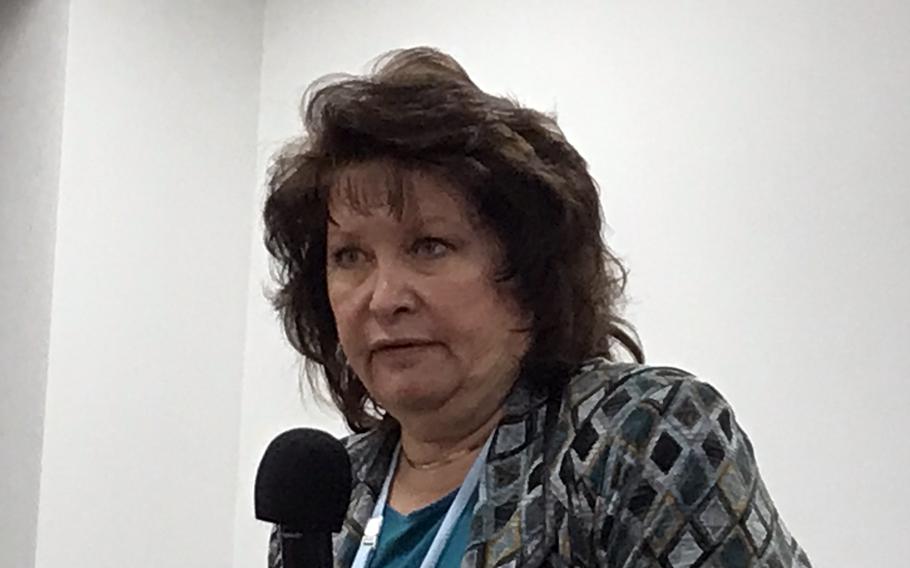

“It is war that is the problem,” Lorna Nielsen Murray, 64, of South Jordan, Utah, said Tuesday during a group discussion at Temple University, Japan Campus. Her father, Army Pfc. Eugene Nielsen, fought on Corregidor, Philippines, as a member of the 59th Coast Artillery Regiment.

The group arrived in Tokyo on Monday for a five-day visit sponsored by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The program — a “gesture of reconciliation” to promote mutual understanding between Japanese and Americans — has been bringing former POWs and their families to Japan since 2010.

The trip, which includes visits to the sites of old POW camps and a meeting with U.S. Ambassador to Japan Rahm Emanuel, is the first since the COVID-19 pandemic and one of the few that have not included a former prisoner.

At the university, the group shared stories about what their parents endured in captivity.

Thomas Hoskins Jr., 75, of San Antonio, Texas, said his father, Army Staff Sgt. Thomas Hoskins, was manning a radar in the Philippines when Japan attacked on Dec. 8, 1941.

As a prisoner, his father was forced to build an airfield on Palawan Island. He was taken to Japan to work in various camps in the Kawasaki area near Tokyo. After the war, his father continued to serve in the military until his retirement in 1959 as a master sergeant in the U.S. Air Force, according to the information provided by the university.

The son, at times close to tears, gave a moving account of his father’s participation in a forced march through Manila where stragglers were shot before the men were packed into stifling box cars and sent to a prison camp. Some of the men died on their feet before the train reached its destination, Hoskins said.

Lorna Nielsen Murray speaks about her father's experiences as a prisoner of war, during an event at Temple University, Japan Campus, in Tokyo, Tuesday, Feb. 14, 2023. (Seth Robson/Stars and Stripes)

Sandra Harding, 70, of Santa Fe, N.M., spoke about her parents, both U.S. Army officers who surrendered in the Philippines: Lt. Earlyn Black Harding and Lt. Col. Harry Harding.

Harding’s mother served as a nurse on the island fortress of Corregidor. Her father was with the 63rd Infantry Regiment (Philippine Army) on Panay Island.

The couple met on Corregidor but didn’t reunite until after the war, she said.

Her mother was interned at Santo Tomas in Manila while her father was sent to Japan and imprisoned at three camps, Harding said.

“My mother thought my father died in a POW camp,” she said. “He found her working in a hospital in Denver and they married in June 1946.”

Murray said her father was one of only 11 survivors of the 1944 massacre of 139 American prisoners on Palawan Island.

The airfield they built for the Imperial Japanese Army is now part of the Philippines’ Antonio Bautista Air Base, according to information provided by the university.

Murray said her father escaped a trench where Japanese guards were burning and shooting prisoners. He was shot several times swimming for his life and linked up with a Filipino freedom fighter. U.S. forces eventually rescued her father and several other escaped prisoners, she said.

On Nov. 22, 2022, Vice President Kamala Harris laid flowers at the memorial on Palawan to the victims of the Japanese war crime, according to information provided by the university.

The veterans’ children shared childhood experiences of parents who hoarded and cherished food after being deprived in captivity.

“World War II should never happen again,” Murray said. “We hope we can prevent such things ever happening again.”