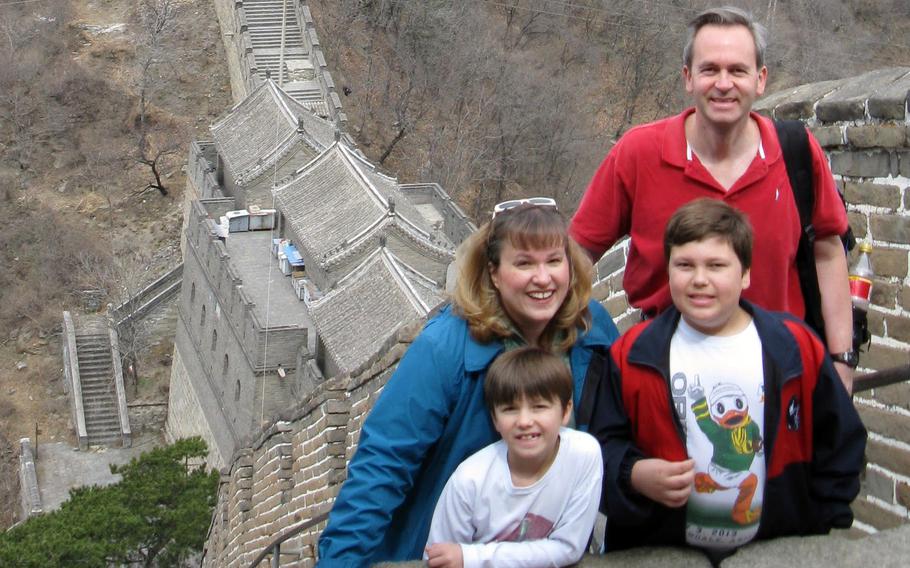

Andrew and Cathy Hakun pose with their and sons Steven, right, and Patrick during a visit to the Great Wall of China in April 2013. (Cathy Hakun)

Stars and Stripes is making stories on the coronavirus pandemic available free of charge. See more stories here. Sign up for our coronavirus newsletter here. Please support our journalism with a subscription.

YOKOTA AIR BASE, Japan — Andrew Hakun, 52, a Navy veteran and father of two boys, died in February 2021 after a long, agonizing wait for surgery following a heart attack at this base in western Tokyo, according to his widow and medical records.

Nearly two years later, Hakun’s death is one example that Defense Department civilian employees raise when they talk about losing access to medical care at U.S. military bases in Japan. Not that Yokota’s 374th Medical Group could have saved his life, but that access to medical care at Japanese hospitals and clinics is unpredictable, they say.

U.S. military personnel in Japan “are living in a country with excellent health care service if you can get to it,” his widow, Cathy Hakun, 57, of Woodbine, Md., told Stars and Stripes by phone Friday. “Anybody on that base who has to go through urgent care is running an unsurvivable risk.”

The Defense Health Agency, under a congressional mandate, imposed limits effective Jan. 1 on DOD civilian employees’ access to most health care at military bases in the Indo-Pacific region. Appointments for immediate medical needs are available only after active-duty service members, their families and other higher-priority individuals are scheduled.

Urgent care and some other services, such as labor and delivery and exams for employment and sports, are still available. Health care at military hospitals in Japan is reserved for those covered by Tricare Prime, the top tier of the military health care plan.

The director of DHA’s Indo-Pacific region, Army Maj. Gen. Joseph Heck, in October advised DOD civilians in Japan to look for health care providers in the communities around U.S. military bases.

During recent town hall meetings, critics of the DHA changes said health care for DOD civilians in Japan has always been hit or miss, that providers can refuse service and often require large, upfront payments for care.

Consequently, DOD civilians working on U.S. bases in Japan risk delayed medical treatment that could prove fatal, Cathy Hakun said. Her husband’s death is a case in point, she said.

Ten tries

The couple, both civilian employees for the Department of Defense Special Representative in Japan, were on their second assignment to Yokota when Andrew Hakun awoke in distress at their on-base apartment, prompting his wife to call 911 shortly after midnight on Feb. 18, 2021, his widow said.

An ambulance arrived within 15 minutes, she said, but her husband was held at Yokota’s urgent care clinic until 4:28 a.m. while attempts were made to transfer him to an off-base hospital, according to his medical records.

Calls were placed to more than 10 nearby hospitals before finding one in Hachioji, 7 miles from Yokota, that would accept him, according to his records.

Andrew Hakun arrived just after 5 a.m. in Hachioji, where Japanese doctors diagnosed him with papillary muscle rupture, acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic pulmonary edema, according to his records. He required emergency heart surgery that could not be performed in Hachioji, the records state.

Hakun went next to a hospital in Shinjuku, about 25 miles from Hachioji, but doctors there discovered severe brain damage due to the heart attack, according to the records, and his family was told heart surgery was no longer an option. He died two days later, his wife said.

Andrew and Cathy Hakun pose with their and sons Steven, left, and Patrick, and their dog, Wooffulls, in Woodbine, Md., Aug. 8, 2017. (Cathy Hakun)

COVID complications

The COVID-19 pandemic, at the time still infecting more than 15,000 people in Tokyo every day, factored into her husband’s death, Cathy Hakun said. He first called Yokota’s hospital on Jan. 28, 2021, complaining of breathing pain. He was instructed to report to a tent outside the hospital for a COVID-19 test rather than come to the urgent care clinic, she said.

“The No. 1 time a man over 50 has a heart attack is in the morning and pain breathing is a sign of a heart attack,” she said.

Persistent chest pain or pressure may be an early warning sign of a heart attack, according to the Mayo Clinic website. Most heart attacks occur between 6 a.m. and noon, according to WebMD.

After testing negative for COVID-19, Andrew Hakun on Jan. 30, 2021, consulted by phone with a Yokota doctor who suggested he come for an in-person checkup; but he decided against it, his wife said.

Thinking back on what happened Feb. 18, she said she should have driven her husband directly to an off-base hospital. He might have received more advanced treatment, faster, she said.

At Yokota’s urgent care clinic, Andrew Hakun was “in full blown cardiac arrest,” his widow said. The staff provided him with aspirin and oxygen and watched, she said.

“They knew it was a heart attack,” she said. “I felt bad for the uniformed medical personnel there. All they could do was watch him suffer.”

Urgent care

Military urgent care centers aren’t typically as well equipped as hospital emergency departments, according to 1st Lt. Danny Rangel, a spokesman for Yokota’s 374th Airlift Wing.

The urgent care staff “are trained and prepared to provide stabilizing cardiac life support to our beneficiaries,” he told Stars and Stripes in an email Aug. 12.

“When medical cases exceed our capabilities, or the patient would otherwise benefit from a higher level of care, medical personnel work with various Japanese medical facilities to facilitate that care,” Rangel said. “The health and safety of our patients is our top priority, and the 374th Medical Group will continue to make every effort to provide the best possible care for all members and beneficiaries.”

Rangel said transportation time for emergency patients to a Japanese facility can vary according to the patient’s condition. Other delays may result when local hospitals are full, a common occurrence during peak periods of the pandemic, he said.

“Our medical staff works with off base facilities to provide the most appropriate and prompt care available in the Tokyo metropolitan area,” he said.

Air Force regulations preclude Yokota’s medical group from disclosing the results of investigations it’s required to undertake when patients are harmed, Rangel said.

“Accordingly, we cannot comment on any specific case, but please know that the 374th Medical Group works tirelessly both internally and with our host nation partners to ensure the best possible outcomes for all patients in our care,” he said.