Stars and Stripes is making stories on the coronavirus pandemic available free of charge. See more stories here. Sign up for our daily coronavirus newsletter here. Please support our journalism with a subscription.

Young women have emerged as a prominent voice of protests over the weekend in China against COVID Zero, a rigid policy that's brought sudden lockdowns and misery to millions of people across the country for months.

On the streets of Beijing and Shanghai, women defied heavy police presence in some areas, joining fellow protesters venting their anger and frustrations on local officials and the Communist Party. Several women were also observed making impassioned speeches despite the risk of possible consequences.

The wider participation of women in the latest wave of large-scale protests underscores their changing role in a conservative Asian society. Even as they expand their share of the labor force in the world's No. 2 economy and pursue their personal life choices, they've been battling workplace discrimination, sexual harassment and gender-based violence.

Women have a particular reason to be angry about the COVID restrictions as they end up handling bulk of domestic chores plus childcare, said one in her 40s after participating in a Shanghai protest. Some women also faced domestic violence, she added, declining to provide her name for safety reasons.

"They have less to lose from protesting, and more to gain potentially" in China's patriarchal society, said Maria Repnikova, an assistant professor in global communication at Georgia State University. "Autocratic regimes tend to construct their legitimacy around conservative family values that don't favor women and women's participation in politics," she added.

The demonstrations that spread online and to university campuses were triggered by reports on social media about how at least 10 people died in an apartment block fire in Urumqi, capital of far western Xinjiang region. China's Communist Party leaders haven't confronted such intense protests since the 1989 Tiananmen movement.

Li, who declined to provide her full name for safety reasons, said she joined one such gathering in an area in Shanghai, adding the demonstrations reminded her of the protests in Hong Kong more than two years ago and in Iran more recently.

"I just wanted to be there," said the 29-year-old advertising industry worker. "It doesn't matter if I'm just standing there. Chinese women are generally more action-oriented and more outspoken than men."

On Sunday night, on the bank of Liangmahe river in Beijing, a woman was seen making a speech questioning why there was no media coverage of the apartment fire in Xinjiang.

In universities, female students weren't just joining protests, but were starting one. Some video clips showed some of them simply holding a piece of white paper and standing quietly, undeterred by their teachers or the mostly male security staff.

But some young women sought to downplay the role of gender in the protests. A one-woman protester in Nanjing, who was briefly taken away by police, posted on Twitter early Monday: "For the basic rights of a human being, there is no difference of gender, location, race. We're all ordinary people fighting for freedom."

The widespread dissent has raised concern that the government may respond by cracking down on the protesters.

"Whatever faith and trust that the government has built is very superficial and material-based," said Li, the advertising industry worker. "People are happy because they are making money and living a better life than they were 40 years ago. Once that is gone, people have no reason to have faith in the Communist Party."

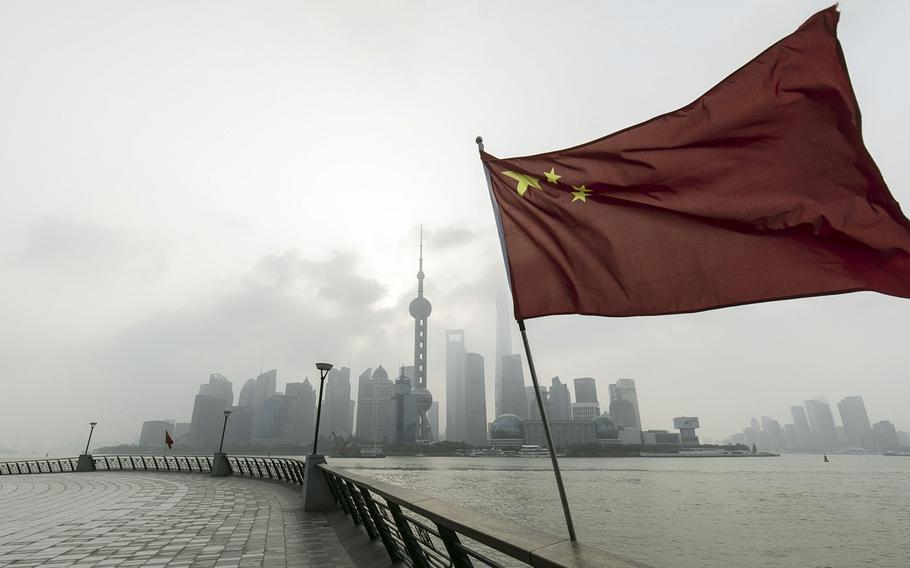

A Chinese flag in front of buildings in Pudong’s Lujiazui Financial District in Shanghai on Oct. 17, 2022. (Qilai Shen/Bloomberg)