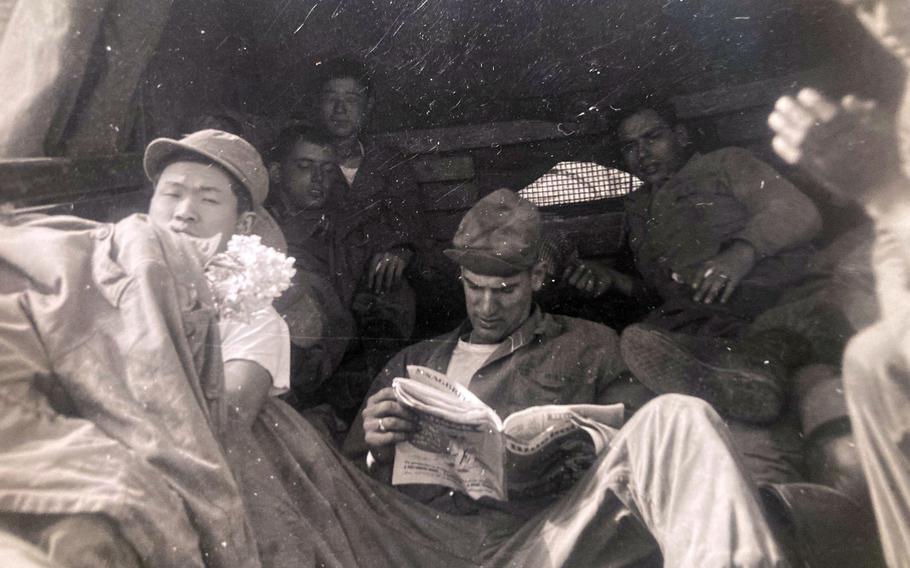

U.S. soldiers relax at a camp in this undated image from the Korean War. (Joseph Mellon)

Soldiers clamber down a net from a ship, fighter jets scream overhead and troops play in the snow in scenes frozen in black-and-white photographs kept by a Korean War veteran from Pennsylvania.

Joseph Mellon, 93, of Hazelton, Pa., collected the photos taken by comrades while serving with the 24th Infantry Division in Korea from October 1951 to January 1952.

Seventy years later, a shoebox in his home holds a photo collection that brings back memories of the “forgotten war.”

Mellon didn’t take the photos and appears in only one of them, reading a newspaper, but they give a glimpse of the lives of front-line troops near what became the Demilitarized Zone separating North and South Korea.

When a draft notice arrived shortly after war broke out in Korea in 1950, Mellon was a 21-year-old civilian mariner on the Charles S. Jones, a tanker owned by the Richfield Oil Corp. of Los Angles, he recalled in a Sept. 29 phone interview.

He trained as an enlisted rifleman and deployed in 1951 to Sendai, Japan, with the 223rd Regiment, 40th Infantry Division of the California National Guard.

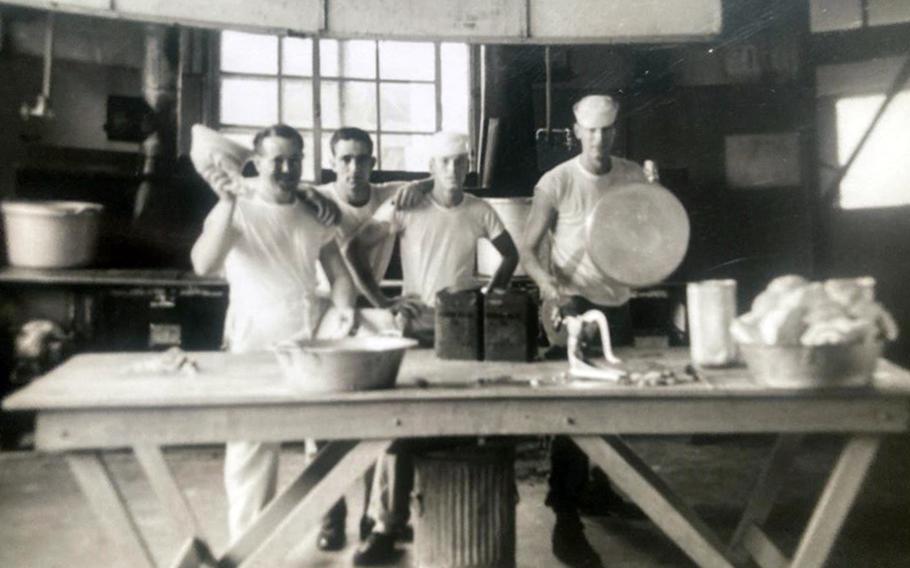

American soldiers pose while preparing food in this undated image from the Korean War. (Joseph Mellon)

His photo collection includes images of soldiers proudly posing in their dress uniforms far from combat.

At that time the 24th Infantry Division was taking heavy combat losses in Korea and the Army called for volunteers in Japan to go there as replacements. Mellon put his hand up and deployed to the peninsula in October 1951, he said.

“The 24th had lost so many men that they needed replacements fast,” he said. “The whole United Nations had made a big push because they wanted to, at least, be at the 38th parallel (before hostilities ended).”

Mellon’s old photos show troops sleeping with their weapons, riding down a dusty road in a military truck, maneuvering in a tank, standing among tents and cooking in a chow hall.

The young rifleman was stationed with the 19th Regiment near the center of the U.N. line in a place known as the Iron Triangle, he said.

The battlefield, Mellon recalled, was littered with dead Chinese soldiers.

“I wouldn’t say they were all over the place, but there were quite a few,” he said. “We had a detail one day where we dragged and piled them up and burned them.”

Mellon said he collected a small Chinese submachine gun called a burp as a war trophy but left it behind in Korea.

The U.N. had concluded its big push by the time Mellon reached the front, but things were still dangerous. His unit lost one soldier killed in action and another was wounded soon after he arrived, he said.

Other photos in Mellon’s collection show soldiers guarding a sandbagged ridgeline and patrolling in Korea’s rugged mountains.

Most of his duties involved escorting South Korean work parties, Mellon recalled.

“We were friendly with the Koreans,” he said. “They worked hard. Back in the rear they would wash our clothes.”

While clearing a field of fire in front of his unit’s position, Mellon discovered a mine that was cleared by explosives experts, he said.

On another occasion a patrol came past his position after passing, unwittingly, through an area booby-trapped with trip wires attached to 40-gallon drums full of napalm, he said.

The troops at the front mostly ate combat rations but were treated on Thanksgiving with a feast before packing up their camp and moving out through the snow to set up a new position, Mellon recalled.

In January 1952, the division was pulled back to Hokkaido, Japan, and replaced in Korea by Mellon’s old unit, the 40th Division, he said.

The troops enjoyed their time back in Japan, visiting the base exchange, drinking beer and hanging out before they were shipped back home, Mellon said.

After leaving the Army in 1953, Mellon rejoined the merchant marine and delivered a shipload of coal to Busan, South Korea, in 1954, he said.

“It was amazing to be sitting in a bar drinking and these guys and girls would come up and offer you morphine or anything else you wanted,” he said. “We could only guess where they got it.”

Army Cpl. Joseph Mellon reads a newspaper in this undated photograph from the Korean War. (Joseph Mellon)

Almost three quarters of a century later, Mellon has a collection of war medals and unit citations from President Harry S. Truman and South Korean President Syngman Rhee, along with his dozens of old photographs.

In hindsight, he said, the war was worth fighting.

“It had to be done,” he said, adding that Truman was right to stop U.N. Command chief Gen. Douglas MacArthur from crossing the Yalu River into China.

“I still have my doubts about it, but I think it was wise to stop him there,” he said.