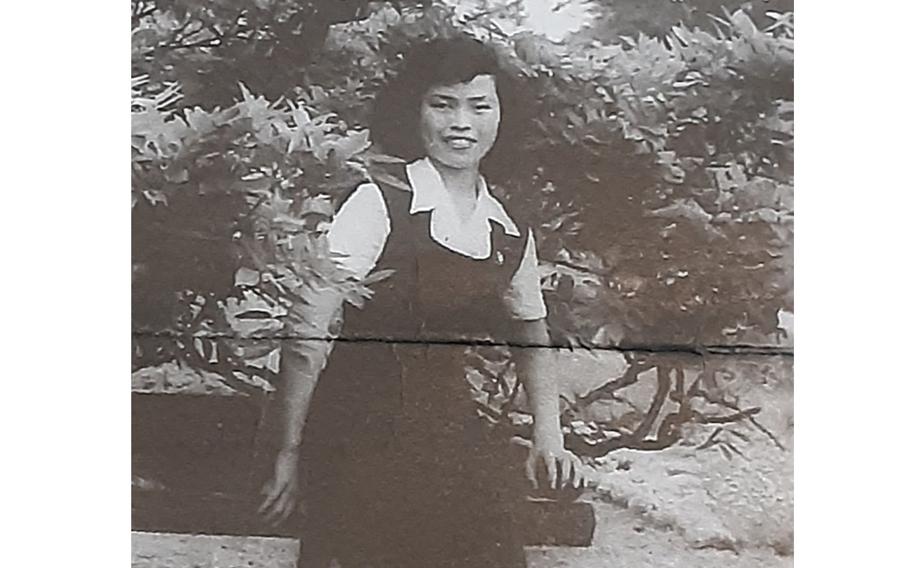

Mann kept this photo of Yamaguchi in his wallet for 70 years. (Rich Sedenquist/The Washington Post)

It was her dance moves that initially got his attention. Then it was her smile and her quick wit. He’d never met anyone like her.

During the Korean War in 1953, Duane Mann — a 22-year-old sailor from Iowa, then stationed in Japan — fell in love for the first time.

Her name was Peggy Yamaguchi, and to him, she was perfect.

“She was such a pretty girl, and so sensitive and kind,” recalled Mann, now 91, who managed an aviation supply warehouse in Yokosuka before transferring to an air base in Tokyo. “We had so much fun.”

The pair met at a military officers’ club, where Yamaguchi worked in the hat check room, and Mann was hired as a mechanic and sergeant-at-arms in his off hours. Yamaguchi took English lessons, and she helped translate conversations between service members and locals.

There was a live band at the club, and one evening after work, “Peggy and I, we started to dance,” Mann said.

“And my word,” he continued, “this girl could really dance.”

They began meeting daily, often until they were the only ones left at the club, dancing to Elvis Presley and Tony Bennett.

“People would just stand and watch us,” Mann said. “Holding her in my arms, I just kept falling deeper and deeper.”

About a year later, their romance came to an abrupt halt when the Navy sent Mann back to the United States sooner than expected.

“The Korean War was over, and the military was bloated, so to save money they started discharging people early,” he explained.

At the time, Yamaguchi, then 22, was pregnant with their child. The young couple came up with a plan: Mann would go back to Iowa, collect the money he had saved in his bank account there — which he put in his father’s name, in case he was killed in the war — and bring his new love back to America.

“I wanted to marry her,” Mann said.

His plan fell through when he arrived in his hometown of Pisgah, Iowa, and discovered that his father had spent all of his savings.

“Every bit of it,” he said. “If I would have known that I didn’t have any money, I would have never gone home.”

While he struggled to find a solution, the couple stayed in touch through letters, and Mann began working at a highway construction company — the highest-paying job he could find.

After a month of correspondence, Yamaguchi stopped replying. Mann later learned why: His mother intercepted and burned Yamaguchi’s letters, as she did not approve of their relationship, he said.

“She didn’t want me to marry a Japanese girl,” Mann explained, adding that his sister snuck him one last letter from Yamaguchi, which arrived a few months later. It said she had lost their baby and married a member of the U.S. Air Force from Wisconsin. “I was devastated.”

A strong sense of guilt swelled up inside Mann. It lingered for seven decades.

“I was worried she thought I abandoned her,” said Mann, who is widowed.

As he moved through life — starting a successful produce business, getting married twice and fathering six children — Yamaguchi never left his mind.

To this day, he has kept two photos of her tucked in his wallet. He tried to track her down, he said, but he never had any luck.

“I wanted her to know that I wouldn’t abandon her,” Mann said.

In a last-ditch effort to find her, Mann posted a plea on Facebook on May 1, sharing a photo he’d taken of her along with the whole story, writing that he carried “a very heavy heart because of what all happened.”

Friends, strangers and internet sleuths weighed in with suggestions. A local news channel, KETV7, picked up the story, spreading Mann’s plea even further.

That’s when a young woman in Vancouver caught wind of Mann’s plight.

“I couldn’t get it off my mind,” said Theresa Wong, 23, who works at the History Channel. “Duane has clearly been looking for closure for seven decades. I can’t imagine how that must weigh on a person.”

She decided to join the search, and soon, “I had her name, the names of her relatives. It all came together very quickly,” she said.

Wong typed in “Peggy Yamaguchi” on newspapers.com, hoping to find a marriage announcement of some sort. A promising article, with the headline “Tokyo Bride Likes Life in Escanaba,” appeared.

“It seemed to line up with everything,” Wong said.

She shared her findings with KETV7, and the station then had a married name and address in Michigan to go on. A reporter contacted Yamaguchi’s son, Rich Sedenquist.

At first, Sedenquist, 66, was puzzled by the message, but once he showed his 91-year-old mother, Peggy Yamaguchi Sedenquist, old photos of Mann, she said, “I remember him.”

Yamaguchi Sedenquist had mostly suppressed memories of Mann, but suddenly, the dancing felt like yesterday, she said. She described her then-boyfriend as “nice-looking, tall, and very honest.”

When she learned Mann was searching for her, “I was very surprised,” Yamaguchi Sedenquist said from her home in Escanaba, where she raised her three sons and still lives with the husband she married in 1955.

Contrary to Mann’s fear, Yamaguchi Sedenquist did not harbor any resentment, she said. When he left Japan, “it was hard,” she recalled, but given that he was in the military, “when he had to go, he had to go.”

Knowing she was alive, Mann was adamant about meeting Yamaguchi Sedenquist in person. Mann’s eldest son, Brian Mann, 63, joined him for the journey.

Growing up, Brian Mann and his siblings had heard stories about his father’s long-lost love, and supported his efforts to reunite with her.

As the father and son drove about 14 hours from Iowa to Michigan for the June 1 meeting, the elder Mann was filled with anxious anticipation. “Do you think she’ll let me hug her?” he asked timidly.

The second he saw Yamaguchi Sedenquist, his worries subsided.

“She got up and gave me a hug, and I got a lot of kisses on the cheek,” Mann said.

The first thing Yamaguchi Sedenquist said to Mann was: “Do you remember the dancing?”

They spent hours reminiscing, and Mann learned that Yamaguchi Sedenquist named one of her sons after him. Her eldest child, Mike, was given the middle name Duane.

“That was really a thrill,” said Mann, who now lives in Woodbine, Iowa.

“It was a special experience,” said Yamaguchi Sedenquist, adding that she assured Mann that she never felt abandoned by him.

Their families also met, and everyone hit it off.

“I had some preconception of what I thought it was going to be like, and it went way beyond what I thought,” said Brian Mann.

“It was wonderful,” echoed Rich Sedenquist. “They are very good people.”

“I just hope I can hang on for another year or two and get to know them better,” added Mann.

What he wanted above anything, though, was to explain what had happened. After seven decades, he finally did.

“I’m at peace with it now,” Mann said.

Still, “I would love to dance with her again,” he continued, “just one more time.”