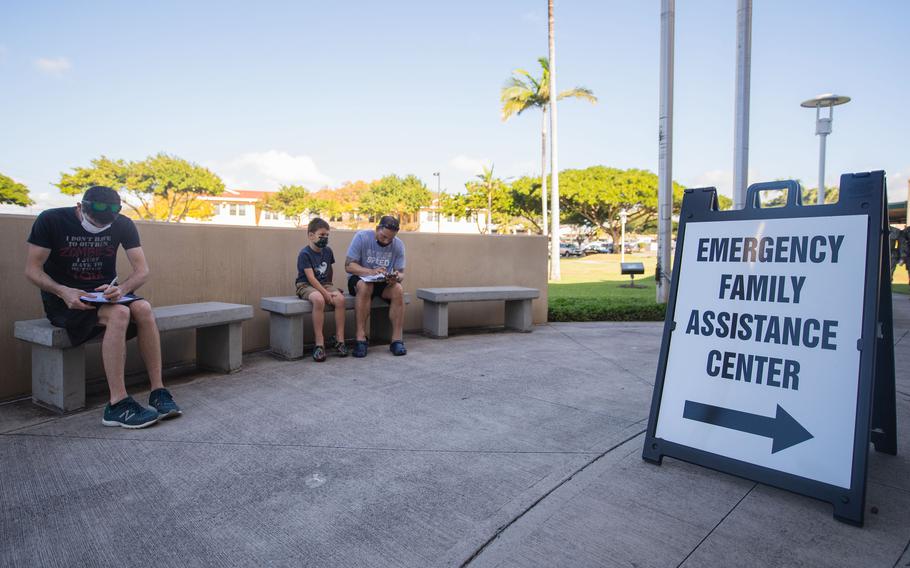

Service members and their families affected by contaminated water file for temporary lodging assistance at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii, Feb. 22, 2022. (Chris Thomas/U.S. Navy)

FORT SHAFTER, Hawaii — Lacey Quintero knows how to handle the stresses of military life. A Navy veteran, the 36-year-old mother of two is married to a Navy officer stationed at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam in Hawaii.

“We’ve been through multiple deployments as a family,” Quintero said Feb. 10 while seated on a picnic table outside the Navy Exchange on the outskirts of the base.

“I, myself, am a veteran with multiple deployments under my own belt, and I know how to handle these things, no problem.”

But she has reached a breaking point. She, her husband Matthew and their two daughters, ages 3 and 5, have been wracked with headaches, nausea, rashes and a host of other symptoms as a result of drinking and washing with contaminated tap water from the Navy’s water distribution system.

They’ve essentially lived in hotel rooms since the end of October, due first to her husband’s transfer in the fall to Hawaii and then, in early December, being among the thousands of families displaced from homes in military communities near Pearl Harbor after petroleum contamination was discovered in a well used by the Navy.

That well was immediately shut down and isolated from the Navy’s other two wells.

The Navy has spent the past two months flushing its water system of contamination as families adjust to hotel life until they can return to their homes.

Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro speaks with Air Force Master Sgt. Norma Ozuna at the Red Hill neighborhood near Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii, about restoring and protecting the island’s drinking water, Feb. 26, 2022. (Shannon Renfroe/U.S. Navy)

The Navy has divided the roughly two dozen military communities on and around the base into 19 zones to manage the cleanup. Water pipes and appliances within homes are being flushed sequentially, beginning with those closest to the contaminated well and moving outward from there.

The Hawaii Department of Health has declared tap water in the first two zones, Red Hill Housing and Pearl City Peninsula, safe for all uses.

Quintero, like many others, however, remains skeptical that the water in the Navy’s system will ever be dependably safe. Despite the costs breaking a lease, she and her husband have sought housing outside of the military community.

‘Not a vacation’

Navy spouse Tracey Contreras bristles over suggestions by some that military families lodging temporarily in hotels are living the good life, lounging beside swimming pools and dining in swanky restaurants along Waikiki Beach’s bustling Kalakaua Avenue.

“This is not a vacation,” Contreras said during a Feb. 9 phone interview from the small hotel room she shares with her husband, a petty officer first class, and her mother, who is paralyzed below the waist and recovering from a form of blood cancer. “This is not fun for us.”

Contreras, 46, moved to the hotel with her mother shortly before Christmas while her husband Eduardo was still in the Middle East on the tail end of a two-year deployment. He rejoined her shortly before the new year.

“My mother is in a hospital bed, and she has to have a wheelchair,” Contreras said. “We were given one room with one bed. I had to ask them if they could remove this tiny couch from the room, and then I myself had to call in a medical company and rent a hospital bed for her.”

Hotel policy prevented them from bringing along Contreras’ two beloved dogs, Lady and Breezy, who had to remain in the family’s water-contaminated home in Earhart Village on the joint base.

Last fall, Contreras said she and her mother began experiencing stomach pains. Contreras developed sinus problems, for which she frequently showered in hot water in hopes the steam would be beneficial.

Contreras said she lost most sense of smell from that condition, but her mother began complaining of a bad smell coming from the water.

Contreras soaked their Thanksgiving turkey and vegetables in tap water before roasting them.

The oven belched a strange smelling smoke that even she could smell, she said.

When she touched the roasted turkey with a carving knife, “it, like, imploded,” Contreras said. “The spine of the turkey, every vertebrae, came apart in pieces.”

They went ahead and ate it.

“Then we were both super, super sick,” she said. News reports about the Navy’s tainted water came out at the end of the Thanksgiving weekend.

Contreras vacillated between anger and anguish as she recalled those events, fuming that the water was contaminated under the Navy’s watch while initially downplaying residents’ complaints, grieving that she gave that water to her ailing mother and two dogs.

Died in her arms

On Jan. 19, the day the Navy flushed the pipes of her home, Contreras was in the house holding Lady, the small dog she confesses as her favorite.

“She made this cry like I’ve never heard before,” she said. As she was carrying Lady upstairs to get her away from the hubbub, the dog gasped for breath, coughed, vomited and died in her arms.

“This is the dog that’s been by my side — my family,” she said. “When my husband’s been away, she’s been my cuddle-bug.”

Despite the flushing, the water in her home remains tainted. In a video she provided Stars and Stripes shortly after the interview, a strange, rainbow-tinged vapor curls up from a pan of water just drawn from the tap.

She expects her family will have no choice but to move back into the home once the Hawaii Health Department declares her zone as having safe water. She is skeptical, however, about official pronouncements on tap-water purity.

She has contacted rental agents about housing elsewhere but found the family could not afford what they would need.

“We’re not officers or anything; we don’t make a ton of money,” she said.

‘A robust picture’

Many of those displaced by contaminated water are not satisfied that only a tenth of homes will be sampled and tested in any given zone before the water is declared safe.

During a Navy daily livestream briefing on Facebook on Feb. 11, Capt. Darren Guenther, chief of staff for Navy Region Hawaii, read a submitted question that many were asking: “How can I be 100% sure my water is OK if it’s not been tested?”

The Interagency Drinking Water System Team — whose members come from the Navy, Hawaii Department of Health and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency — developed and approved the plan to begin with an initial sampling of 10% of houses in each neighborhood, Guenther said.

“But that’s just the start of a long-term testing and monitoring process,” he said.

The Navy will test an additional 5% of homes during a three-month period following the initial testing, Guenther said.

“That gives them a robust picture of the entire zone,” he said.

At the four-month mark, the Navy will test another 10% of homes or buildings and do so again every six months for a two-year period.

“Cumulatively, by the time the first two years of testing has concluded, as many as 60% of all the structures will have been tested,” Guenther said.

The science of cleansing

Some residents regard the testing scheme as unreliable because of widespread inconsistency of contamination from house to house.

Bonnie Russell, who along with her Navy husband Lawrence, a petty officer first class, and four children were displaced from their home in Caitlin Park, is among those leery of the testing protocol.

“I just wish they were testing more than 10% of the houses because when they did the initial home testing — and I had requested my house be tested — [contamination] showed up as trace,” Russell said during a Feb. 7 phone interview.

“But two doors down from me was the highest result in any private home,” she said.

“I’m not sure I’m ever going to trust the water in the sink again.”

The Navy did little to bolster her confidence, Russell said, after the service earlier this year issued guidance to residents for cleaning household items of petroleum contamination.

They were directed to clean children’s items that are porous, such as bottles, pacifiers and sippy cups, with dishwashing detergent.

Russell said she and other residents asked the Navy to provide the scientific basis used to determine that commercial dish soaps could remove petroleum contamination.

Unsatisfied with the response, Russell contacted four of the world’s largest detergent manufacturers, including Procter & Gamble and Colgate-Palmolive, and asked if any of their dish soaps were effective at removing petroleum contamination from porous surfaces.

All four responded that their products had not been tested to perform such a task, she said.

On the other hand, the Navy’s guidance to residents for cleansing porous surfaces in items such as coffee machines, ice makers and water dispensers was to simply run large quantities of water through them.

“It’s all very contradictory,” Russell said. “Why is plain water going to clean out my dishwasher or refrigerator or water dispenser, but not a baby bottle?”

‘All of this inside our bodies’

Back at the exchange, Lacey Quintero said her family is in the process of moving into a 1,200 square-foot apartment in a community beyond the Navy’s water system. They signed a lease for the apartment, sight-unseen.

The Quinteros arrived in Hawaii from San Diego on Nov. 6 and checked into the Navy Lodge on Ford Island.

“We began drinking tap water at the Navy Lodge,” she said. “That’s the first day we were sick. I personally have been sick since that day.”

They moved into a home on Nov. 21 at Officer Field on the joint base. They were not there long.

“Everyone in my family took drastic health downturns when we moved in,” Quintero said. Their daughters could not sleep at night, plagued with full-body rashes and canker sores in their mouths.

“But I had to stop focusing on my kids because my husband and I were so ill,” she said. “We were up at 3, 4 in the morning just vomiting, with diarrhea, violent stomach cramps, burning like fire in our throats.”

The family stopped using the water on Nov. 29, after news broke about possible contamination. They moved into a Waikiki Beach hotel on Dec. 4 when the Navy offered to pay for temporary lodging.

The Navy has flushed the family’s house twice, Quintero said. But petroleum fumes in the home give her “an instant headache” upon entering.

Lab tests she and her daughters underwent this month revealed highly elevated levels of toxins associated with petroleum products.

The risks of moving back into Officer Field are too great to chance, Quintero said.

“Now that we have all of this inside our bodies, we can’t afford to have any more put in,” she said.