Samuel Phillip Bickett walks his dog, Mui Mui, on Aug. 17, 2021, in Hong Kong. The corporate lawyer was convicted and jailed for assaulting an officer. (Anthony Kwan/for The Washington Post by)

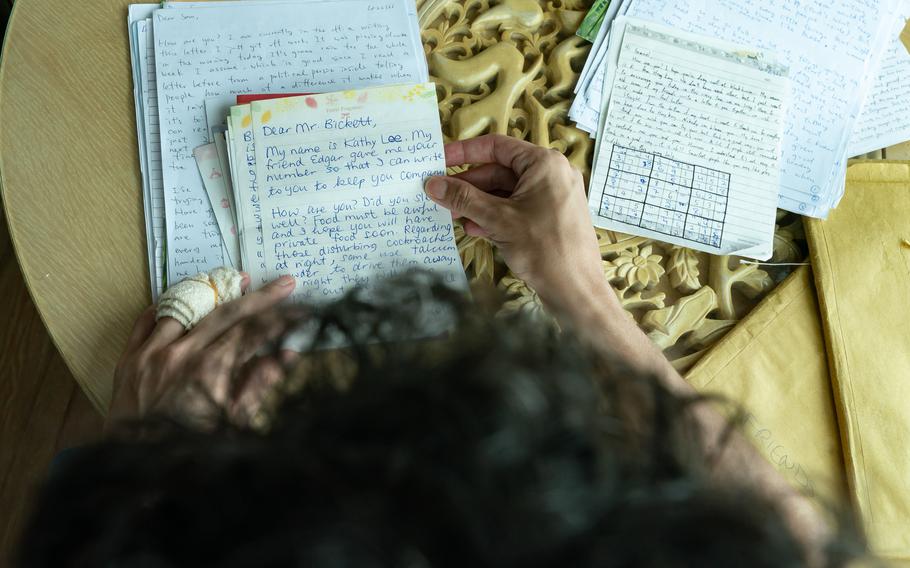

HONG KONG — Soon after his transfer to the maximum-security Stanley Prison in July, guards approached Samuel Bickett with a stack of letters written by people he had never met.

Some were neat, others in cursive or messy scribbles. But themes of hope, support and solidarity were repeated, page after page.

“Thanks for standing with us,” one woman wrote on stationery featuring an otter in a flower crown. “The only thing we can do is to write letters [to] give some spiritual support to our siblings.”

Bickett, 37, arrived in Hong Kong nine years ago as a corporate lawyer handling cases for American companies in Asia. But his fate has come to embody fears about a diminished rule of law in the Chinese territory and the unchecked power of the police force, after he was convicted and jailed for assaulting an officer who identified himself as such only after arresting Bickett. He is on bail and appealing the verdict.

“What I realized reading these letters is that to people, [my case] doesn’t just represent the destruction of the rule of law, it represents a destruction of values,” Bickett said in an interview. “I feel this immense burden not just to get justice on appeal for me but ...for all these Hong Kongers who supported me.”

As China remakes Hong Kong in its authoritarian image after anti-government protests in 2019, the American’s experience offers a glimpse into a prison system filling with political detainees. His case is among those testing the degree to which the former British colony — which China promised autonomy, including independent courts, until 2047 — retains judicial independence, a reason many Western corporations base operations here.

No police officer has been arrested, charged or punished for any act related to the 2019 unrest, when police faced criticism for a heavy-handed crackdown on sometimes-violent protests. Eric Lai, a Hong Kong law fellow at Georgetown University’s Center for Asian Law, said the courts have tended to treat police “not as individuals or as police, but as a symbol of law and order.”

“We can see the overall jurisprudence, regarding law enforcement, is weighted more towards the police,” he said. “Overall, the police are not punished for abusing their powers.”

A spokesman for Hong Kong’s Justice Department referred The Washington Post to an earlier statement in which the department took “exception to the serious accusation made against our legal system arbitrarily and without basis.” In a previous letter to The Post, the police force said it “refutes the baseless accusation that the Hong Kong Police Force is emboldened by impunity” and said the off-duty officer had been upholding the law.

Bickett was going to meet a friend in December 2019 when he saw a man hitting a teenager with an extendible baton. An altercation ensued between the man, identified later as Yu Shu-sang, and bystanders. Yu lunged at Bickett and fell over a railing, before Bickett subdued him and tried to wrestle the baton away.

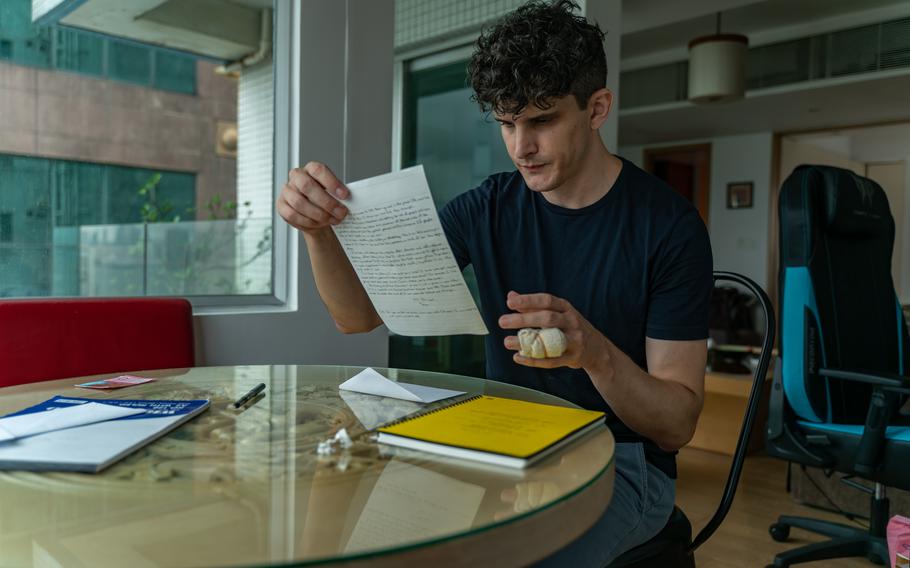

Samuel Bickett reads the letters he received during his detaining time in jail on Aug. 16, 2021 in Hong Kong. (Anthony Kwan/for The Washington Post by)

Yu then moved to arrest Bickett and said he was an off-duty police officer apprehending the teenager for jumping a turnstile. Until this point, Yu had repeatedly answered “no” when onlookers asked if he was “popo,” a slang term for a police officer.

Hong Kong police guidelines state that officers, on or off duty, must identify themselves as such and produce a warrant card when conducting duties. The judge who found Bickett guilty said the officer could not be expected to respond accordingly as the crowd was being “disrespectful” by using a slang word for police.

Bickett, a former compliance director for Bank of America Merrill Lynch, was sentenced to four months and two weeks for assaulting a police officer and for common assault. The magistrate, Arthur Lam, called his acts “a serious threat to public order” that could have “incited a bigger conflict.”

Bickett and his lawyers were shocked. “To commit this crime, you have to have actual knowledge that he’s a police officer,” Bickett said. “And there’s a video of this guy saying he is not a police officer.”

After the verdict, Bickett was strip-searched. His hands and feet were shackled and he was taken to Lai Chi Kok Reception Center, a decades-old jail complex for men that houses most of Hong Kong’s jailed democracy activists and others awaiting trial in connection with the 2019 protests.

Bickett was given a tube of toothpaste, a toothbrush, a bar of soap and a hand towel, the only supplies he would get until friends could provide more. But other inmates who had read about the case quickly recognized Bickett and began sharing their M&Ms, the only approved chocolate in Hong Kong jails, and other small luxuries.

When inmates learned that Bickett was a lawyer, they began to form lines around him, asking for legal advice. Soon, he was running a sort of pro-bono legal service from behind bars, in some cases connecting inmates with people outside who could help with bail or other issues.

Samuel Bickett sends letters to people within the Hong Kong prison system to show his support, and many detainees invite the public to keep in touch. (Anthony Kwan/for The Washington Post by)

Friends who visited Bickett said he would use 15-minute visitation slots to present them with a to-do list of inmates to help. One visitor, Stephen Palmquist, a philosopher who at that time was a professor at a local university, said Bickett was more interested in talking about mutual friends and an employment dispute between Palmquist and his employer than about his own plight.

“He had drips of sweat coming down his face which he was trying to wipe off,” said Palmquist, who visited him in July. “He was putting up with an extremely physically uncomfortable situation, not to mention the psychological discomfort.”

After Bickett was sentenced and moved to the maximum-security prison, friends could visit him only twice a month.

Inmates in Hong Kong prisons have complained of severe heat in the summer, akin to “living in a steamer.” Changes have been enacted since a May petition, including new fans and iced towels for inmates. In letters from prison, activists have chronicled their encounters with roaches and other insects.

Some inmates appear to have been punished for seeking better conditions. A former member of a Hong Kong independence group who was detained pending trial filed a request that female prisoners be allowed to wear shorts like their male counterparts because of the heat. Her cell was searched and she was put in solitary confinement for seven days, according to a prison rights activist. Others have been put in solitary confinement for hugging or for sharing stamps with fellow inmates, rights activists have reported. This month, elite officers and police dogs were deployed to quash a suspected protest.

Chris Tang, Hong Kong’s security chief, said jailed activists who have amenities such as extra chocolate or hair pins could “harm national security” by amassing a following among other detainees.

Bickett said prison rules were selectively enforced to target perceived troublemakers. He said that although most inmates around him were detained on drug charges, he had met some who were being held on political charges, including under a national security law designed to quash dissent.

Bickett said the experience has shaken him. While preparing his appeal, he is no longer confident in Hong Kong’s courts and is bracing for a return to prison, he said.

“I’ve committed my entire career to the law. I believe in the law,” Bickett said. “But that was utterly crushed by what happened to me and what I’ve seen happen to other people in this city.”