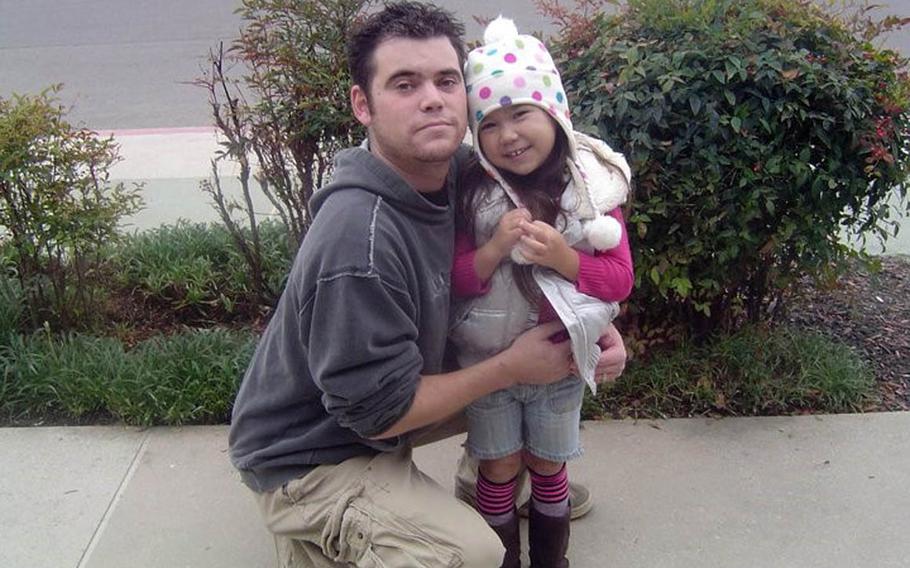

Donny and Christina Conway pose near their former near Naval Air Station Lemoore, Calif., in this undated photo. Conway hasn’t seen or heard from his daughter, who is believed to be in Japan, since 2012. (Donny Conway )

YOKOSUKA NAVAL BASE, Japan — The last memory Donny Conway has of his daughter is watching her push him away just before putting her to bed.

“Momma told me if I hug you, she’s going be mad at me,” is what Conway recalls hearing from Christina, then 6.

Conway, who was a petty officer 2nd class at Lemoore Naval Air Station in California at the time, left his child’s room and told his soon-to-be ex-wife, Yumiko, never to say such a thing to his daughter.

A week earlier, Yumiko had returned from a trip to Japan and had asked for a divorce. Conway says she missed Japan and worried about his financial stability because he was among 3,000 sailors involuntarily released from the Navy because of what was then perceived as an overmanning problem.

In granting Yumiko’s divorce request, Conway expected resolution through the U.S. court system, he said.

Instead, on Aug. 9, 2012, the morning after seeing fear in his daughter’s eyes over a bedtime hug, he woke up to an empty house.

He later learned that his wife and daughter were in Japan, and he hasn’t heard from them since.

“I have no idea whether or not my daughter is even alive,” Conway said.

Yumiko Conway, right, and her daughter, Christina, pose in this undated photo. Conway is believed to have brought her daughter from California to Japan in 2012 during divorce proceedings, without the consent of the father, former sailor Donny Conway. The father has not seen or heard from them since. (Donny Conway )

Conway’s case is not unusual — the State Department and Federal Bureau of Investigation have noted several dozen incidents of child abduction to Japan in recent decades.

Japan’s adoption of the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction in April 2014 offers some remedy to that trend, according to experts; however, cultural and legal obstacles remain among parents hoping for either child custody or increased visitation.

Parents can apply for help through either the State Department or the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs under the Hague Convention.

The Japanese will attempt to locate the child and set up a mediation process. If that fails, the parent seeking the child can petition family court.

In October, the new system returned its first child to a German parent abducted by a Japanese mother. Two more Canadian children were returned in December.

To date, five abducted children have been returned to Japan under the convention, according to Foreign Ministry data.

Parents whose children were abducted before Japan joined the convention can’t petition for a return, though they can petition for visitation.

The idea of joint custody remains an alien concept in Japan, said Colin P.A. Jones, a professor at Doshisha Law School in Kyoto. Jones has written extensively on Japanese family law for several years.

Until the 1960s, the father tended to get custody of a child following a divorce, Jones said. At that point, societal shifts tended to favor maternal custody, often to the point of excluding the father from the child’s life.

Meanwhile, what Americans have viewed as criminal abduction, Japanese society has viewed as a normal part of divorce.

When considering custody and visitation, judges wield a substantial amount of discretion over any factor they think might harm the child, Jones said. If a foreign parent gets an arrest warrant issued after an ex-spouse abducts a child, the judge might even rule against a return on the grounds that a parent’s potential arrest would scar the child.

“It’s very common to do whatever it takes to bring the child back,” Jones said. “But having an arrest warrant may actually be counterproductive in long run.”

Although Japan has returned a few children, it remains to be seen just how cooperative the country will be over the next few years, Jones said.

The main sticking point is enforcement, Jones said. If Japanese officials try to contact the parent of an abducted child, then it can be argued that they’ve fulfilled their Hague Convention obligations, Jones said.

If one parent doesn’t cooperate, the legal remedies remain unclear. Even if both parents cooperate, the Hague Convention’s applicability doesn’t guarantee a result.

“Where there has been something of a sea shift in courts is in accepting that visitation is good for children,” Jones said. “But the court can be completely on your side, and you still may not get very much.”

Petty Officer 1st Class Erik Schaefer, a Navy corpsman based in Okinawa, found out recently how difficult life can become when the court isn’t on a parent’s side.

Shortly before returning from Afghanistan in May, Schaefer’s Japanese wife emailed him, telling him she was divorcing him.

His ex-wife refused to speak with him or tell him where his 4-year-old son and 9-year-old daughter were living.

Schaefer says he went for help at Camp Foster’s legal office but said they couldn’t assist because his wife was already a client. He went to Kadena Air Base, where the legal office gave him a list of Japanese lawyers.

When court mediation began, Schaefer agreed to sign legal custody over to his ex-wife after being told joint custody wasn’t an option.

“The mediators involved in the process kept making it very clear at the time that they believed a child had the right to see a father, and they kept reassuring me on this,” Schaefer said.

Between his Afghanistan deployment and his wife’s actions, Schaefer hadn’t seen his children in about a year and a half, until he saw them again in court in December.

The children shied away from him, and the judge noted it. The judge also asked several questions about an alcohol-related incident in Schaefer’s past, though he sought counseling afterward and hasn’t gotten in any trouble since.

In January, Schaefer received the verdict: one hour of supervised visitation every two months. When Schaefer transfers to another duty station and comes to Japan to visit, he will still only get one hour to see his children.

Schaefer had two weeks to appeal the decision but didn’t know it because it had taken two weeks before he received the decision back from a translator, he said.

He has since hired a local lawyer to review the court proceedings in a desperate attempt to change the ruling.

“I’m not expecting the world,” Schaefer said. “Just enough that the kids feel like they have a dad.”