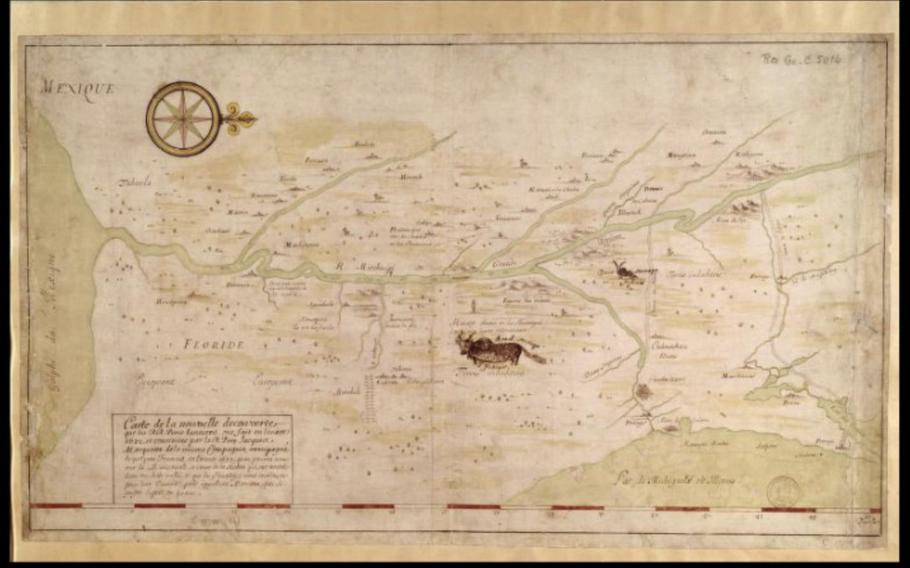

French Jesuits mapped the Gulf of Mexico, “Golphe da Mexique” in 1672 in an expedition lead by Father Jacques Marquette. (Library of Congress)

Colonizers have always coveted the Gulf of Mexico: its trade winds, ports, fish and shellfish, its deep pockets of oil and gas far beneath a basin floor of crashed, tectonic plates.

“This superb gulf belongs to us exclusively,” was the sprit of England’s imperial ambition back in 1797, according to a news report from the Negotiations at Lisle by a Scottish newspaper, which predicted that the British had their designs on harnessing the gulf’s trade winds.

That rapacious bravado has the same flavor as President-elect Donald Trump’s recent declaration that he’ll rename the Gulf of Mexico the “Gulf of America” because “it’s ours.”

This expansionist agenda comes right after President Joe Biden included the gulf in his last-minute ban on offshore oil drilling, curbing pursuit of the treasure far beneath the floor of the world’s largest gulf.

The gulf was formed almost 200 million years ago, when tectonic plates separated and crashed, creating a “super basin” and trapping organic matter in pockets beneath the land, which became the crucible for massive reserves of oil and gas.

“Much of the remaining oil lies buried beneath ancient salt layers, just recently illuminated by modern seismic imaging,” according to researchers at The University of Texas at Austin.

That wasn’t what first attracted humans to the gulf. It was home to busy ports and trade routes for the Mayan and Aztec empires, a source of food and salt, which was valuable in trade. It was named for the Mexica, what the Aztecs called themselves in the Nahuatl language, according to linguist T.S. Denison’s 1913 book.

Spanish explorers tried to erase the Mexica when they first arrived and put this gem on Europe’s conquering to-do list. They showed its vast, curving shore on a map they presented to the continent in the 16th century and called it “Golfo de Nueva España.”

The name clearly didn’t take, although the conqueror’s use of the gulf when traveling back and forth to Spain made it colloquially known as the “Spanish sea,” according to historian Robert S. Weddle’s book of the same name.

About 100 years after the Spanish floated the “New Spain” label, French Jesuits drew the gulf on their map in 1672, calling it “Golphe da Mexique.”

The French colonizers made their stand in Mexique more than 150 years later, blockading Mexico’s vibrant ports during the Pastry War. Yes, French aggression in Mexico involved croissants.

The Guerre des Pâtisseries was sparked in 1838 after a pastry chef in Mexico complained to King Louis-Philippe that the widespread civil unrest following Mexico’s independence from Spain included the ransacking of his bakery.

The gulf was the road to riches, the quickest route for luxury goods: gold, silver, cotton, sugar, spices, enslaved people. And that brought the pirates.

“An American brig from Madeira for N. Orleans, is reported to have been taken in the Gulf of Mexico, and BURNT by a FRENCH PRIVATEER, probably the same privateer which lately fired on a U.S. vessel,” the Portland Gazette reported on Sept. 9, 1811.

News reports of pirating — part of the marine lists printed in local newspapers — were like the maritime crime blotters of the early 1800s, logging the ships, the deaths, the cargo, the locations of the attacks.

Congress finally got fed up and passed a bill in 1819 called “An Act to protect the commerce of the United States, and punish the crime of piracy,” and sent armed cutters into the Gulf of Mexico.

The gulf was becoming a vital part of the American economy, a freeway for exporting slavery’s cotton and sugar crops. New Englanders began moving south to farm the waters as commercial fishing expanded offshore in the mid-1800s.

“The fisheries of the Gulf also grew as the richness of the resource, with massive schools of fish, attracted settlers, especially those seeking to stake out claims not to land but to work on the water,” according to a study in the Journal of Maritime Archeology.

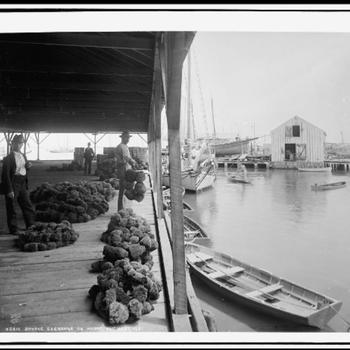

A sponge exchange wharf in Florida between 1890 and 1901, when sponges from the Gulf of Mexico made up a third of the state’s marine industry. (Detroit Publishing Co.)

By 1895, Florida’s sea sponge industry accounted for a third of the state’s annual marine revenue, according to architectural historian John Sledge, who wrote “The Gulf of Mexico: A Maritime History.”

“No longer was the Gulf a Spanish sea,” Sledge wrote. “It was an American sea.”

That dominance continued when the United States discovered the treasures beneath the gulf’s waters.

A historic marker in Morgan City, La., contains a pelican and the state of Louisiana above its inscription marking the day humans began the massive underwater and underground harvest of the gulf. This time, the treasure was oil.

“THE FIRST OFFSHORE OIL WELL: First producing offshore oil well out of sight of land was completed Nov. 14, 1947 in the Gulf of Mexico forty-three miles South of Morgan City, Louisiana,” it says.

The first, massive oil spill happened in 1979, when millions of barrels of oil spilled into the ocean, covering a 1,100-square-mile area in the gulf after oil well Ixtoc-1 had a blowout. Hundreds of miles of Mexican and U.S. coastline was slicked and mucked with oil.

Three decades later, that spill was dwarfed by the Deepwater Horizon disaster of 2010, when 206 million gallons of oil gushed into the gulf for three months.

Not long after, a Mississippi state representative proposed a bill to mock the anti-immigrant sentiment in his state by attempting something that hadn’t been done since the “New Spain” gambit of the 1600s.

“They want to kick immigrants out of the state. They want to get rid of anything that’s not ‘America,’ ” state Rep. Steve Holland, a Democrat, told NPR in 2012.

“So I just thought it would be in keeping to introduce a bill to change the name of the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of America,” Holland said, reminding Americans of the “Freedom Fries” episode of 2003, when some folks protested French opposition to the U.S. invasion of Iraq. His bill died quickly.

Trump supporter Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) is now promising a bill supporting the “Gulf of America” campaign, as Biden announced plans to ban offshore oil drilling by invoking part of a 1953 law, the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act.

The ban would include parts of the Gulf of Mexico’s eastern shore, along the Florida coast where the Spanish conquistadors first landed almost 500 years ago.