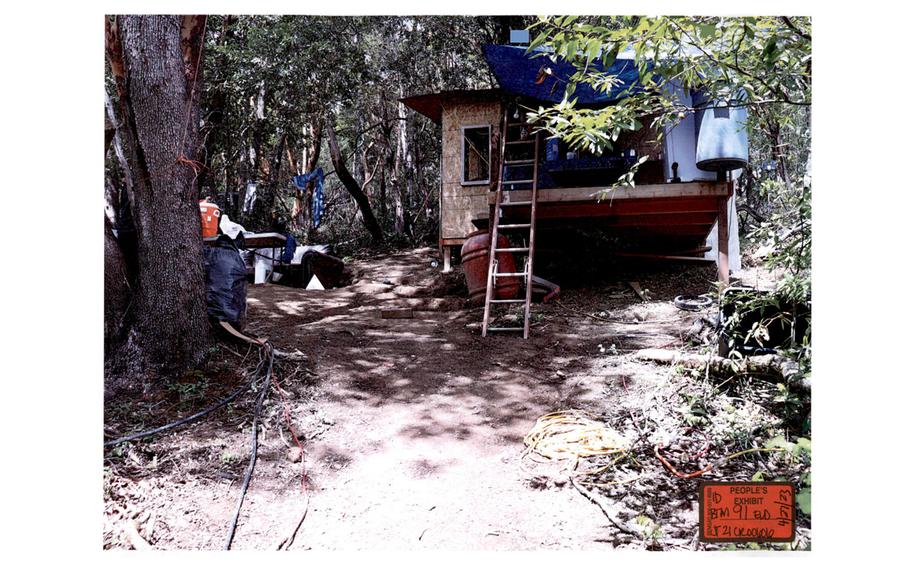

The plywood shack where workers bunked on Chris Gamble’s cannabis farm in Mendocino County, California. (Mendocino County Superior Court/TNS)

PÁTZCUARO, Michoacán (Tribune News Service) — In a small square crypt behind frosted glass in subtropical Michoacán is incontrovertible proof of the cost of California cannabis.

The tomb just within the high cemetery gates of the Panteón Municipal de Pátzcuaro, flanked by sunflowers in twin blue vases, holds all that can be found of Ulises Anwar Ayala Andrade.

Sharing the crypt is what remains of Ulises’ teen son, a convivial boy named after his father, but whom everyone affectionately called “Chino.”

For two decades, “Ulises Zapatero” sold shoes in Pátzcuaro’s open air market, beckoning passersby to his racks of colorful Nikes and Pumas.

The shoe stock was bought with high-interest loans, and the Ayalas carried a mortgage on the family of five’s simple house in the outskirts above Pátzcuaro. Struggling with those debts, Ulises obtained a tourist visa for the United States in early 2020 and, intending to find work, boarded a bus north.

Joining him was 16-year-old Chino.

Their quest for U.S. dollars would take them deep into California’s Emerald Triangle at the height of a runaway cannabis market, to a crude shed on a Mendocino County farm, beside other Mexican laborers in the underground economy.

Traveling in the other direction were coffins.

From the southern Mojave Desert to the mist-shrouded mountains in the northern ranges, the California green rush was exploiting and killing workers.

Relaxed criminal penalties and expanding markets had set off a massive boom in illegal cultivation. Even on licensed farms, California regulators failed to protect workers in the labor-intensive industry.

A Los Angeles Times investigation documented widespread exploitation, wage theft and disregard for worker safety and housing.

The newspaper found 44 farm-related deaths, surveying just a five-year period in only 10 counties. Among them was an 8-month old infant who died in Trinity County from an undetermined cause. The rest were workers.

All but five of the deceased were immigrants.

A third of them came from Mexico.

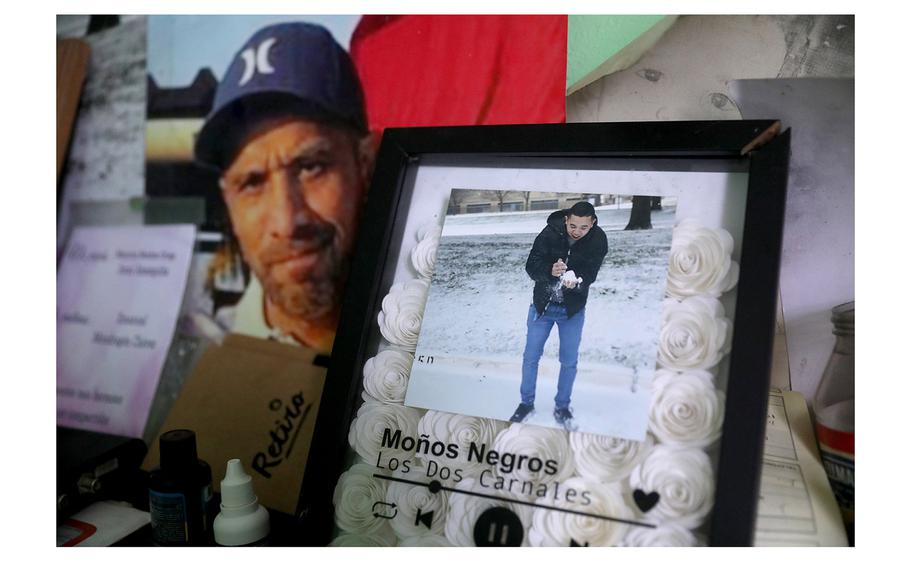

Family photos of Ulises, and of Chino while still in Dallas, fascinated by snow. (Gary Coronado/Los Angeles Times/TNS)

The Ayala family lived outside of Pátzcuaro, a tourist arts haven of Spanish colonial plazas and red-tiled roofs. Ulises sold tennis shoes in Pátzcuaro’s lively central market, where a multitude of vendors called “pásale” — come on by — to peddle their wares of lake fish, dried hominy, home goods and woven shawls and fine embroidery.

At a folding table near Ulises’ shoe racks, his wife, Josefina, ladled out bowls of aromatic pozole.

At night, the family returned to their hillside colony of two-story houses erected like barnacles on the still-visible foundations of one-room casitas. Just a decade ago, one out of five domiciles still had dirt floors. Today, a third of the streets remain rutted clay, traversable only by foot.

The Ayalas could afford just the basics — an old car, a little furniture. The loans to restock Ulises’ racks dragged the family down. The reliable sales of Josefina’s pozole lifted it up. All night long, the stew’s garlic perfume filled the still air of the concrete house, simmering for market the next day.

“We lead a life, well, that is not so good,” Josefina told Ulises as she tried to persuade him not to leave the country to find more work, “but we are together.”

For Ulises, it was not enough.

And there was the question of Chino’s direction.

“He didn’t see much for himself in studying,” said the teenager’s closest childhood friend, Guille Perez.

The boy’s bedroom was filled with name brand street wear — Adidas backpacks and Bad Bunny T-shirts, and a rack of 13 colorful tennis shoes. During long walks with Guille, the visions Chino shared of his future revolved around earning money. “He planned to work,” Guille said, “and maybe someday buy something, like a car, a house …”

In early 2020, with shoe sales slumping and debts mounting, Ulises and Chino left to find work in Dallas.

It was a bust.

Ulises had been promised a job hanging mechanical doors. But in the opening days of the COVID-19 pandemic, the work was meager. He failed to earn even $300 a week.

“I’m worse than ever,” he told Josefina by phone.

Come home, Josefina said.

But Ulises heard from an old friend from Pátzcuaro, whose family had moved to Northern California. She said her brother in Mendocino County could give Ulises a lot of work.

“Hay mucho trabajo,” she told Ulises. The pay would be enormous by his standards: $10,000 for three months.

Ulises agreed to go to California. Soon, Chino followed.

Illegal cannabis has a controversial but largely tolerated footing in Mendocino County.

The crop is the economic lifeblood for small, stagnant towns like Willits, devastated by the closing of sawmills. The sheriff estimates the county’s redwood forests house more than 5,000 cannabis operations, the vast majority likely to never go legal and unlikely to ever be visited by the sheriff’s two-man narcotics squad.

Even on the most peaceful homestead farm, to convert crops into cash requires dealing with the drug trade. Guns are common, as are armed robberies, shootouts and other mayhem. The first season Ulises and Chino were in Mendocino, a pair of Las Vegas security guards donned body armor and tried to heist a money delivery to an illegal operation in nearby Covelo. The robbers failed to make a clean getaway, leading to an armed standoff with police that ended when the ringleader shot off the top of his head in a botched suicide.

The cannabis community is also deeply segregated by race and class. Growers who own their own land are predominantly white. Those who work it are predominantly people of color, such as traveling work crews of older Hmong who immigrated decades ago, young Argentinians staying only for the summer, and crews assembled by Mexican labor contractors.

The latter are frequently branded “cartel,” a label that both creates a class of outsiders and discounts the suffering of those on that side of that fence.

“We live in fear of the cartels,” said an older white resident and longtime grower outside Willits, speaking of the shared conviction within her rural community of cannabis farmers that if there is bloodshed, a “cartel” can somehow be blamed. Another resident contended Mexican workers come from a “second world” country so violent that they value life less than do “Caucasians.”

Mendocino County has actually had no cases, arrests or prosecutions tied to Mexican narcotics cartels.

But those dying on Mendocino County cannabis farms since California legalized weed in 2016 have all been Latino workers.

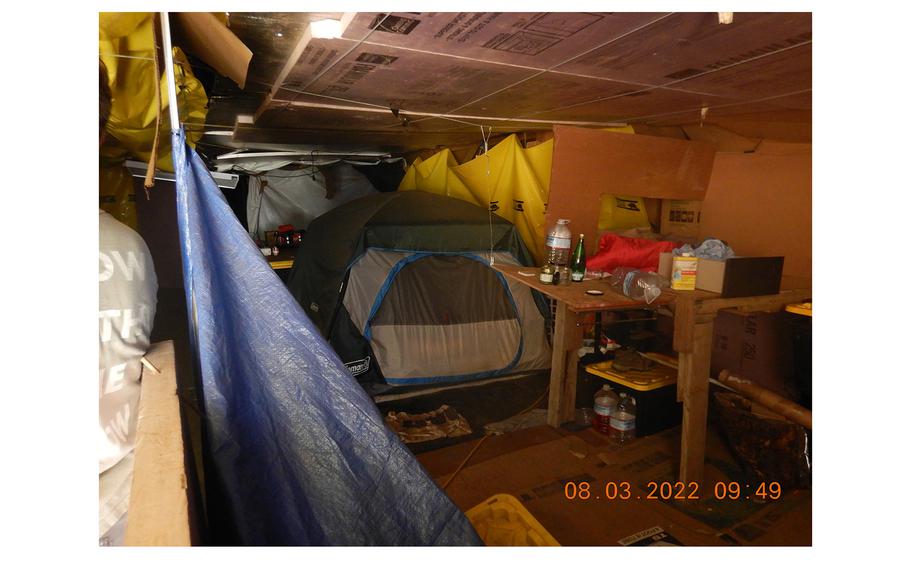

Worker tents in a state-licensed Trinity County cannabis farm, a year after county citations for housing violations and the unexplained death of an infant. State cannabis investigators also inspected the farm, before and after the death, but its license remains active. (Trinity County Health Department/TNS)

In keeping with statewide patterns found by The Times, four of the men were laborers poisoned by carbon monoxide from greenhouse generators. Four others were murdered, including 19-year-old Ramon Naranjo Casteneda, a U.S. citizen who had lived with his father in Mexico. His body was dumped on the highway outside of Covelo, a holster for trimming shears on his belt and still smelling of fresh weed.

A ninth man, a San Jose flea market vendor seeking to support his family during the COVID-19 shutdown, vanished and is presumed dead.

Though state and federal worker-protection laws cover such laborers, those deaths and dozens more identified by The Times were not investigated by labor agencies. Their absence from the record makes the cannabis industry appear safer than it is, avoiding scrutiny or protections that might prevent additional deaths.

The Department of Industrial Relations, responsible for labor safety in California, said in a press office email that it “takes all worker deaths extremely seriously.” In response to stories published in The Times, the agency said it was educating sheriffs on legal requirements to report workplace deaths and also had conferred with state cannabis regulators, though it would not release public records showing it had done so.

When presented by The Times with details of dozens of farm deaths, the agency opened a single investigation — into the October 2021 carbon monoxide poisoning of Michael Puttre.

Puttre was asphyxiated by fumes from a generator. He had been working as a building contractor at a state-licensed cannabis farm in Humboldt County. The owner, contesting a $34,000 fine for failure to provide a safe sleeping space, disavowed responsibility.

“What Mr. Puttre did with his free time and sleeping arrangements was his decision,” the farmer’s lawyer wrote to a state investigator.

Only through a sheriff’s deputy did the investigator learn Puttre’s sleeping quarters was a 30-foot hoop house, the kind used to grow cannabis.

Ulises knew the man offering him work in California.

There was a time even when he and Jose Manuel Archundia Martinez were business partners, selling shoes at the tianguis— small markets — outside Pátzcuaro, traveling from village to village.

The fortunes of the men diverged greatly after Archundia moved to the United States.

After a decade in the country, the social media pages of the Archundia family flash totems of prosperity — a dancing show horse, expensive trucks and racing cars, and gold chains adorned, in one case, with a gold AK-47, and in another, a fighting rooster.

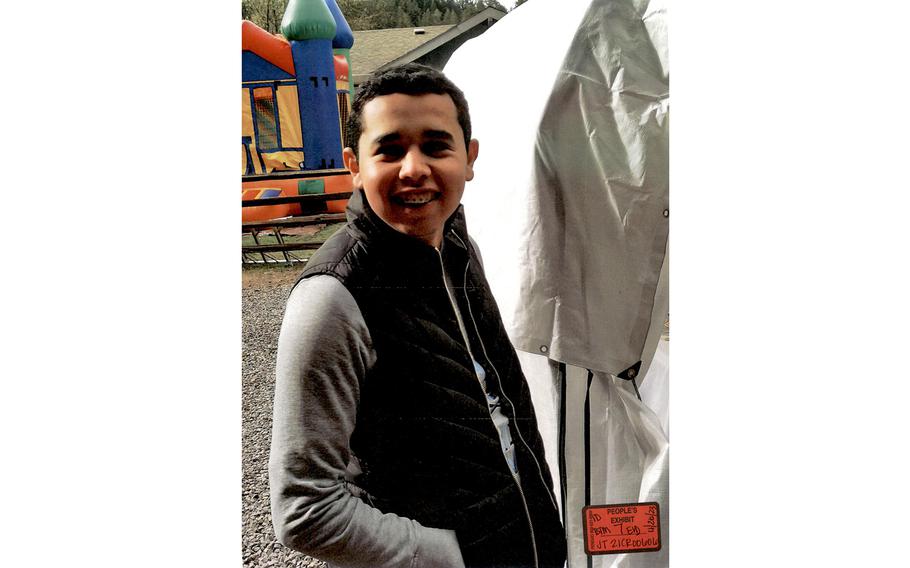

Ulises Anwar Ayala Rodriguez, aka Chino, hours before his death. (Mendocino County Superior Court/TNS)

But whereas Archundia lived on the expansive ranch of a prominent local housing developer, he sent his cannabis crew — Ulises and Chino and another man and youth — to stay beside the greenhouses they tended, in an unpainted plywood shed.

The workers had access to the bathroom of a nearby cabin but mostly showered with water from buckets hung to warm in the sun. They relaxed on a pair of couches parked outside beneath the trees. The dirt around the shed was littered with chip bags and beer bottles.

Josefina came twice briefly to visit and formed an instant dislike.

She was distressed to find Ulises eating instant ramen, and to see her husband and son deslumbraban— dazzled — by the Archundia money, the cars and trucks. Ulises even changed his Facebook profile to a big red truck like one in the Archundia drive. He asked Josefina to stay in California.

She refused.

“My son, I don’t pay attention to any of it,” Josefina at one point told Chino. “Because there are things very valuable to me: to be here, to have my mother, and have [my children], and have my job, and have peace.”

She returned to Pátzcuaro alone, holding on to the belief Ulises and Chino would follow.

It rained in the night, and by early morning one Sunday in April 2021, the dirt lane that sloped down the Mendocino County ridge was slick with mud. Gadiel Ortega Hernandez told his girlfriend to drop him off at the gate, and the portly man carefully picked his way down the hill to reach work.

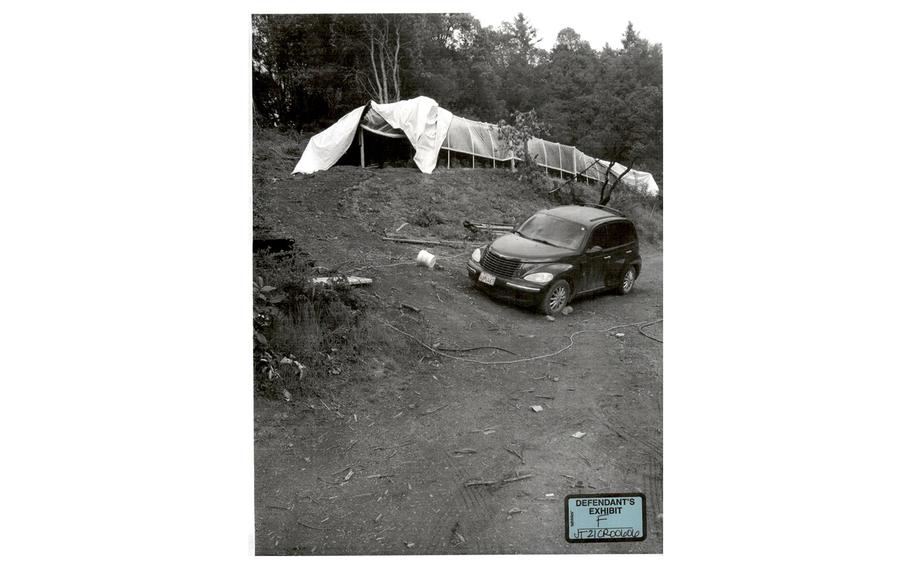

Through the thick woods he could barely see the poles of a grow house, but rounding a curve, Ortega was in the clearing. Before him loomed three large greenhouses terraced into the slopes, each teeming with young cannabis plants. It was April and they were still small, but being pushed toward early flowering with a double dose of artificial light at night, sun during the day.

Given the early hour and the tequila consumption at the boss’ ranch the night before, Ortega didn’t expect to see anyone moving. But a light-blocking tarp had already been pulled from one large greenhouse. And tilted at an odd angle on the slope below it was the PT Cruiser that Ortega’s coworkers had used to come home from the party, the purple car’s passenger door hanging open.

They got up with a lot of spirit to work! Ortega thought. They arrived so drunk they didn’t even park.

Yet Ulises and Chino were nowhere in sight.

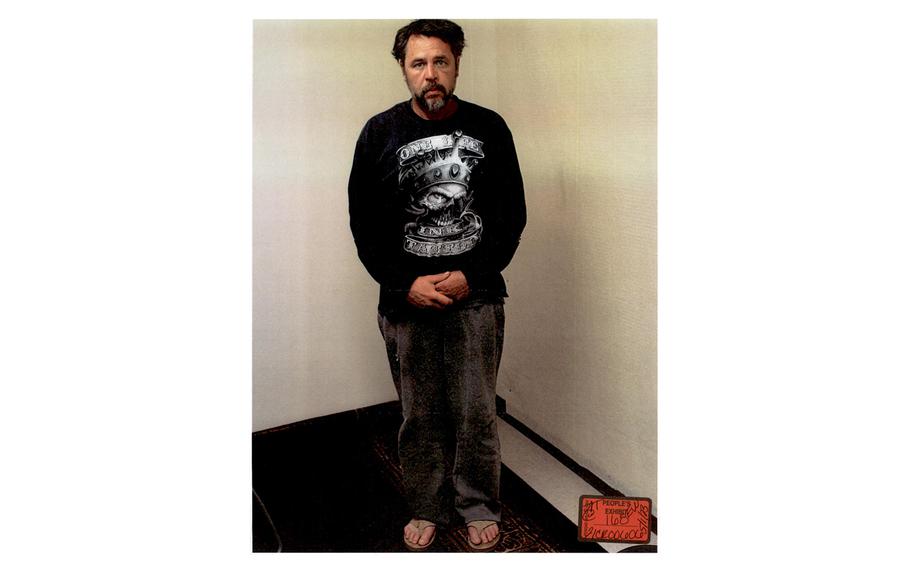

Chris Gamble during police questioning. (Mendocino County Superior Court/TNS)

Instead, coming down from the tiny bunkhouse Ortega shared with the other farmworkers was Chris Gamble, the tousled middle-aged man who leased this land and owned two adjacent parcels where the crew was adding greenhouses. In Gamble’s arms was what looked like a white comforter.

“Qué pasó Chris?” Ortega asked.

“Nada. No pasó nada,” Gamble replied. “I fought with Ulises.” Gamble clasped his hands together, fingers pointing like a gun, acting out for Ortega a scenario in which Gamble claimed Ulises had threatened him.

So now, Gamble said, the father and son from Mexico didn’t work there anymore.

“Se fueron lejos,” Gamble said. They went far away.

Gamble, in his mid-40s with a paunch and bowl-cut hair, could look unimposing when needed, like confronted by someone with a gun, or standing for a police mug. He provoked vastly contradictory impressions.

His mother called him “granola.” A neighbor said he was “sweet,” even if he did once intentionally lock the fire marshal onto his property. In a courtroom feud with a neighbor over his barking pitbull, Gamble produced an elaborate narrative in the dog’s defense, replete with reconstructed conversations, and 17 character witnesses who vouched not only for the dog but called its master “caring,” “warm,” “respectable,” and “kind.”(For all that, Gamble still was ordered to restrain his pitbull, Guinness.)

Yet Gamble’s ex-wife and former girlfriend lodged domestic abuse complaints against him and sought the protection of court restraining orders. Gamble was ordered into anger management class, and still remained on criminal probation, forbidden from owning the many handguns and the assault rifle stashed in his ridge-top cabin. There was an order to pay child support, and warrants and citations for failing to appear in court, resisting arrest, burning without a permit and entering a closed disaster area.

To his Mexican business partner, who typically added a vulgarity to the label, Gamble was a “marijuana hippie loco.”

Cannabis had been Gamble’s means of support for two decades, supplementing a meager disability check. He said seizures prevented him from working at the family sawmill in Potter Valley, or making use of his community college training in medical aid and firefighting.

Year after year, Gamble’s cannabis ventures suffered misfortune. After his workers walked off the job halfway through the 2019 season, he was ready to turn over control of the farm to a neighbor down the road who said he could expand the yield with light-controlled greenhouses: Manuel Archundia. In return, Gamble would receive a 30% cut in whatever crop Archundia produced, typical of the sharecropping arrangements popularized with the expansion of illegal farming.

Gamble called Archundia “the bank.” Archundia fronted the money and goods for Gamble’s cannabis operation. And Archundia recruited the work crew: Ulises and Chino, along with Ortega and the son of Ortega’s girlfriend.

It wasn’t an easy relationship. Gamble complained about the Spanish-speaking workers, saying they didn’t know what they were doing. And the workers came to regard Gamble as reclusive and odd, an impression reinforced for Ortega that Sunday morning.

Ortega peered within the PT Cruiser. Ulises’ phone and Costco card were on the seat. Water streamed from a hose and across the floorboard. The early morning wash seemed strange, but Ortega was not yet suspicious.

He turned his back on Gamble and set to work, draining rainwater sagging the greenhouse tarps. Gamble lingered for awhile, halfheartedly helping, then drifted off.

Only when Ortega was done with the greenhouses did he take the trail to the bunkhouse, an unheated shed barely large enough to accommodate a camp cot used by Ortega and the bunkbed where Ulises and Chino shared the bottom berth while another worker took the top.

Ortega saw the wet floor, the tossed clothing — and only then noticed the puddle of blood outside in the dirt.

Covertly, he charged his cell phone off a greenhouse generator, then fled.

By the time Archundia picked up his worker from the ridge road, Ortega was weeping.

Gadiel Ortega repeats for sheriff’s deputies Chris Gamble’s explanation for the missing cannabis workers. (Mendocino County Superior Court/TNS)

In Chris Gamble’s calculus, violence was a cost factor in the cannabis business.

Over the years, he had been shot at, hit with a bean bag bullet, tied up with zip ties, and repeatedly ripped off.

“If your guy gets shot and murdered, you get nothing and you lose another friend,” he told a judge. “It’s the black market, sir. Nothing is guaranteed.”

Archundia operated by different math. The first thing he did after collecting the weeping Ortega from the road was have one of his English-speaking sons summon the sheriff. The son made only a brief attempt at hiding the fact the missing men were workers on the family’s cannabis grow.

Deputies rousted a freshly showered Gamble from bed. They found a collection of prohibited guns, 345 pounds of dried cannabis flower, 800 cartridges of cannabis oil concentrate, and three greenhouses filled with young plants — a crop Gamble estimated was worth $1 million.

In a still-smoking fire pit down in the woods, they found burnt tires, charred chickens and two headless corpses.

That Gamble had killed the missing Ulises and Chino was evident: There was gunpowder on his hands, blood on his belt, 9 mm casings outside the bunkhouse and blood on the ground, the walls and the cot.

But “to this day,” said deputy district attorney Scott McMenomey, “I don’t know why he killed them.”

Details of the events leading up to the deaths of Ulises and Chino come from cellphone texts, court testimony and their killer’s own retelling.

April 24, 2021 began sweetly.

“Buen día, mi amor,” Ulises texted to his wife, the last Josefina would hear from her husband.

It was to be a day of celebration.

Celebrants at a fateful baptism party include Gadiel Ortega, far left, and Ulises Ayala, far right. (Mendocino County Superior Court/TNS)

First, the fiesta in the woods, where Gamble said Archundia staged a large cockfight on Gamble’s land, replete with taco stand and beer truck. Archundia and his workers denied the existence of the fighting roosters, but police found many betting slips and leg bands for cockfights.

Later that day the party moved to Archundia’s ranch 10 minutes away, to celebrate the baptism of a grandson. Cellphone photos show Ulises with the other workers, their arms around one another, beside a shiny red truck. In another, Chino sported a rare open grin, revealing braces, as he stood in front of a children’s bouncing house.

There was plenty of tequila, and a minor drunken fight. Gamble remarked to one of Archundia’s sons that the laborers from Pátzcuaro, now on their second season, were “worthless” — at least as far as skills in growing cannabis went.

After dark, Ulises and Chino drove back to the farm in the Cruiser, taking Gamble with them. The two other workers went off into Willits to sleep.

The rest of the story came only from Gamble, who took the stand during his double-murder trial. Over the course of four hours, Gamble provided a characteristically elaborate version of events:

The headlamps of the PT Cruiser threw light on a black bear crossing the road as they pulled up to the gate, Gamble said, so he gave Ulises his 9 mm pistol to scare off the animal. Then it started to drizzle, and Gamble ordered the workers to help him pull off the heavy tarps that normally shielded the greenhouse lights from view, so the plants could soak up the rain. Chino obeyed, but Ulises refused, saying that was not what Archundia wanted.

“If you can’t follow directions, you don’t have a job here,” Gamble threatened, speaking in his poor mix of Spanish and English.

Ulises reddened, and waved the gun about. Gamble lunged for the pistol, and it fired, shooting Ulises in the neck and dropping him dead to the ground.

Gamble stumbled out of the bunkhouse. He could not stop Chino from entering and seeing his father. Gamble said he tried to make himself look “real small” and unthreatening, but Chino took his father’s Ruger off a shelf, and he came after Gamble.

So Gamble shot the boy, another fatal wound to the neck.

The rusty revolver in Chino’s hands was special to Ulises exactly because it was so decrepit, Gamble said.

First, the revolver had no firing pin, so could not shoot a bullet unless the end of a toothpick was inserted into the hole of the missing mechanism.

Second, the cylinder would fall out unless held in place with two hands. When Chino fell, the gun hit the ground and the loose cylinder rolled out. Gamble noticed it was empty.

Chino had no bullets.

At first, Gamble said, he sat in the rain, trying to breathe, his mind a muddle.

Then he thought of his $1 million crop.

“The police would be here ... and I had a huge sum of marijuana there that is, ultimately, how I sustain my family and myself,” he told the jury. “And the thought of losing that ...

“That’s a huge loss, you know, life-altering loss.”

The purple PT Cruiser, parked askew below a cannabis greenhouse. (Mendocino County Superior Court/TNS)

He couldn’t move the weed — both trucks on the farm were inoperable, and Archundia’s purple Cruiser had no hitch.

Gamble believed his partner would share his interest in protecting the crop above the disappearance of two Mexican workers. He expected the two men would talk, and Archundia and his sons would help him figure out the “logistics.”

“I didn’t think that they would call the police,” Gamble said.

“I mean, I really didn’t.”

Gamble set about to “lessen the shock” of the crime scene, so that when Archundia and his men saw it, they wouldn’t just shoot him right there and then.

He dragged the bodies of Ulises and Chino from the bunkhouse down to the Cruiser, and went back to his house for a steak knife. He had decided to remove the heads.

Then Gamble drove the corpses to his burn pile in the woods.

He threw in tires. He grabbed trash. In his haste to build a hot fire, he also tossed in a burlap sack. Only too late did he realize it held living roosters from the cockfight, he said.

Then Gamble drove the Cruiser past Archundia’s ranch, until he came to a field with hogs. He threw them the heads.

He had just finished up washing out the bloody Cruiser and bunkhouse when Ortega showed up for work.

From the witness stand, Gamble indicated an area on a map where he had seen the hogs. The judge put the trial into recess and every available deputy and investigator left the courthouse to walk the fields in a futile search for skulls.

In May, Gamble was sentenced to life in prison without the chance of parole for the first-degree murder of Chino Ayala, second-degree murder of Ulises Ayala, and felonious abuse of animals for the burning of chickens. From Wasco State Prison, his case on appeal, Gamble declined to talk to a reporter.

“I am fighting for my life and my freedom,” he wrote to The Times.

But in a now-sealed pre-sentencing report, one that Gamble said is biased and erroneous, a probation officer quoted the convicted murderer calling his victims “drug users” and “not good for society.”

In an appeal for leniency, Gamble offered the probation officer a final justification.

He claimed his Mexican farm manager, the shoe salesman he incinerated, the boy he beheaded, all were “cartel.”

Siblings Guille and Estefanny Perez find it difficult to understand the murder of their best friend, Chino. (Gary Coronado/Los Angeles Times/TNS)

The California murders hit hard in Pátzcuaro, which enjoys a relative reprieve from the violence that stigmatizes some other parts of Mexico.

The Ayala family had not been told about the beheadings — that was learned two years later when the murder case went to court, the horrible news gleaned secondhand because Josefina could not afford to attend the trial.

Josefina, her family, and Chino’s friends battled immobilizing grief and depression. For days Josefina couldn’t bring herself to work. She relied on sleeping pills. And the family’s financial predicament worsened. Ulises had never received all of the promised wages, though Archundia’s sister sent $900 collected through GoFundMe to help with the funerals. For two years, Josefina could not pay the mortgage.

Guille Perez, Chino’s best friend, retreated within his house, then within himself. An acquaintance from the United States warned him the deaths of Mexicans gathered little attention across the border, dispiriting Perez further. He had trouble accepting that Chino’s killing was real.

“Until now,” he said in a voice so soft it barely carried across his living room, “I did not acknowledge that he had died.”

The Ayala family slowly adjusted. Ulises and Josefina’s eldest child, Tania, reopened her father’s shoe stall. Their youngest, Aldo, quit school to help at the market. And Josefina repainted their brown house to a bright aquatic blue. On most days, she is at the market in her red and white apron, chatting with customers as she serves pozole.

But there is a hollowness in her life.

“In fact, I’m not fine,” she said in Spanish, her voice quaking.

“Vivo porque tengo que vivir.”

I live because I have to live.

Times staff photographer Gary Coronado contributed to this report.

©2023 Los Angeles Times.

Visit at latimes.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.