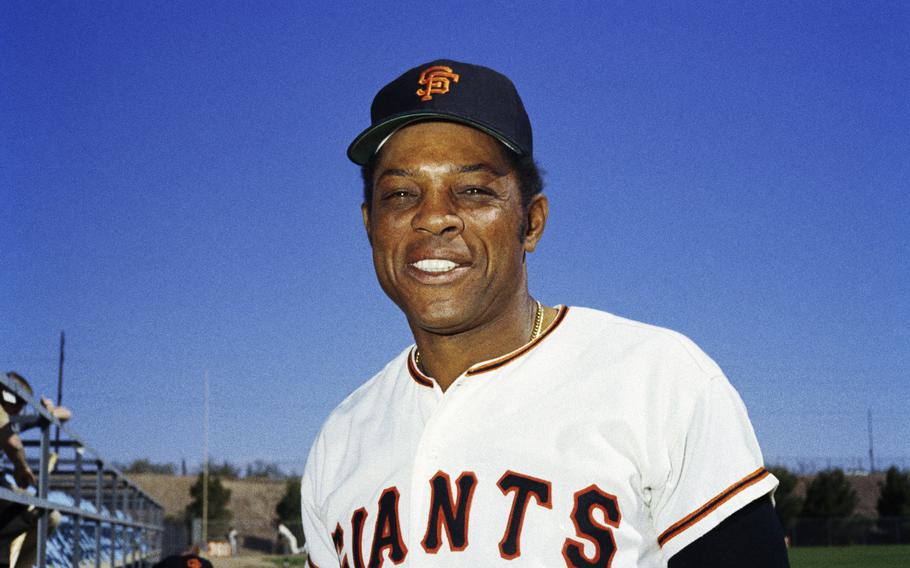

New York Giants' Willie Mays poses for a photo during baseball spring training in 1972. Mays, the electrifying “Say Hey Kid” whose singular combination of talent, drive and exuberance made him one of baseball’s greatest and most beloved players, has died. He was 93. Mays' family and the San Francisco Giants jointly announced Tuesday night, June 18, 2024, he had “passed away peacefully” Tuesday afternoon surrounded by loved ones. (AP)

Willie Mays, a perennial all-star center fielder for the New York and San Francisco Giants in the 1950s and ’60s whose powerful bat, superb athletic grace and crafty baseball acumen earned him a place with Babe Ruth atop the game’s roster of historic greats, died June 18. He was 93.

The San Francisco Giants announced his death on social media but did not provide other details. Mays was the oldest living member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

“If there was a guy born to play baseball,” Boston Red Sox legend Ted Williams, one of his 1950s contemporaries, said late in life, “it was Willie Mays.”

With such demigods as Jackie Robinson and Hank Aaron, Mays, from Jim Crow-era Alabama, was one of the earliest Black players to reach exalted heights in the formerly segregated major leagues. His body of work from 1951 to 1973 included 660 home runs — then the third most of all time — despite a nearly two-year absence for military service.

Baseball has had 150-plus players with higher career batting averages than Mays’s. There have been swifter base runners and a few more-prolific sluggers over the decades. But Mays could do it all: The record book says no one showcased a more formidable combination of power, speed, arm strength, wizardry with a glove and steady hitting than No. 24 of the Giants, whom many regard as the best defensive center fielder ever.

Most devotees of hardball history consider Mays second to Ruth in the game’s pantheon. Some rank Mays ahead of Ruth, an ace pitcher turned outfielder for the New York Yankees who revolutionized the sport with his titanic bat in the Jazz Age. Advocates for Mays argue that Ruth didn’t possess May’s all-around skills and never had to compete against Black major leaguers.

At 20, Mays was National League rookie of the year and helped the Giants reach the 1951 World Series. His 3,293 career hits — including 10 hits in the old Negro American League that were added to his total in 2024 — gave him a robust .301 lifetime average. He was named to 24 All Star teams in 18 seasons, some in years when two such games were played.

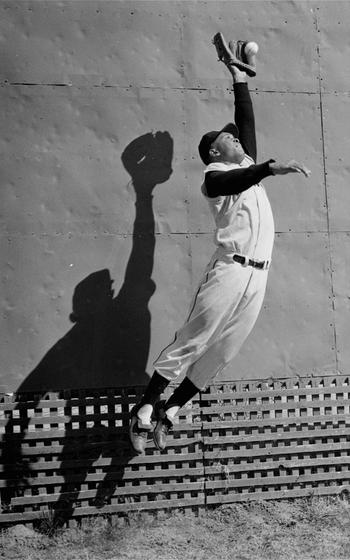

While a lot of sluggers were brawny and less than nimble in the field, Mays, listed on Major League Baseball’s website as 5-foot-11 and 180 pounds, dominated opponents with his glove, legs and throwing arm. A miraculous catch he made in the 1954 World Series, racing toward the center field wall with his back fully turned to the infield, is among the most celebrated plays in the annals of the sport.

New York Giants center fielder Willie Mays leaps high to snare a ball near the outfield fence at the Giants' Phoenix spring training base, Feb. 29, 1956. Mays, the electrifying “Say Hey Kid” whose singular combination of talent, drive and exuberance made him one of baseball’s greatest and most beloved players, has died. He was 93. Mays' family and the San Francisco Giants jointly announced Tuesday night, June 18, 2024, he had “passed away peacefully” Tuesday afternoon surrounded by loved ones. (AP)

Starting in 1957, Mays won 12 consecutive Gold Glove awards for defensive excellence in center field, the most spacious position, where quick reactions and fleetness of foot are paramount. He collected more Gold Gloves than any other center fielder in history, even though the award didn’t exist until his fifth full season. At the same time, his disruptive speed and guile as a base runner augured a revival of an undervalued aspect of the game.

In the 1950s, a decade loaded with fearsome hitters, the “small ball” tactic of base stealing was mostly an afterthought — but not for Mays, the first player with 300 or more career home runs to also tally at least 300 thefts (he swiped 339 bases). Only seven others have done it since. Although his yearly totals weren’t jaw-dropping by later standards, he stole more bases (179) in the 1950s than anyone else in the majors.

“Willie Mays is the greatest player I ever laid eyes on,” declared his first Giants manager, Leo Durocher, a teammate of Ruth’s in the late-1920s.

After Robinson broke baseball’s racial barrier in 1947 with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Mays, three weeks out of his teens, became the 17th Black player to arrive in the big leagues. He debuted for the New York Giants on May 25, 1951, and went hitless in 12 at-bats on the road. Then, in his first plate appearance at the Polo Grounds, the Giants’ old ballpark in Upper Manhattan, he recorded his first hit — “a towering poke that landed atop the left-field roof,” the New York Times reported.

Counting the home run, Mays, a right-handed batter, began his career 1-for-26, a miserable stretch. “I was crying,” he recalled almost 70 years later. “I wanted to go back” to minor league Minneapolis. But Durocher kept him in the lineup, insisting, “Son, you’re my center fielder.” After Mays found his stroke, he finished his rookie season with 20 homers and a .274 average.

In scouting parlance, he emerged as “a five-tool player,” with exceptional abilities to hit for power, hit for average, run, field and throw. Yet plenty of five-tool stars have come and gone. What made Mays transcendent were the dazzling degrees to which he excelled at all five skills for the better part of two decades.

Known for his full-throttle energy on the diamond, his joy and brio, Mays was a headliner in the postwar golden era of New York baseball, before the Giants and Dodgers decamped to San Francisco and Los Angeles to start the 1958 season. During that Gotham heyday, one or two of the city’s three ballclubs, led by the dynastic Yankees, played in 10 World Series in 11 years — including seven “subway series” — and each team featured a Hall of Fame-bound center fielder.

“Willie, Mickey and the Duke,” the song goes: Mickey Mantle (and before him Joe DiMaggio) of the Yanks, Brooklyn’s Duke Snider and Mays, who as a rookie would often play stickball with youngsters in front of his Harlem rooming house. Afterward, he’d treat the kids to ice cream, then walk to work at the Polo Grounds.

“Snider, Mantle and Mays — you could get a fat lip in any saloon by starting an argument as to which was best,” columnist Red Smith reminisced in 1972. “One point was beyond argument, though: Willie was by all odds the most exciting.”

In the outfield, where the durable Mays compiled a record 7,095 putouts, he caught a lot of balls unconventionally, holding his glove near his belt buckle for his signature “basket catch.” And he admitted to wearing ill-fitting caps to ensure that he would run out from under them as he dashed around the bases or chased a long flyball.

“You have to entertain people,” he told sportscaster Bob Costas in 2006. “That’s what I wanted to do all the time.”

Mays’s nickname, the “Say Hey Kid,” was bestowed by a New York sportswriter who noted the young player’s habit of chirping “hey” when he had something to say (as in “Hey, how you doin’?” and “Hey, where you been?”), according to biographer James S. Hirsch, author of “Willie Mays: The Life, the Legend,” published in 2010.

With 660 career homers, Mays ranked third, behind Aaron and Ruth, until 2004, when the Giants’ Barry Bonds — Mays’s godson — eclipsed him. In 2015, Alex Rodriguez also passed Mays in home runs. But Rodriguez and Bonds were tainted by evidence of illicit steroids use. Albert Pujols, who has never been credibly linked to steroids, hit his 661st homer in 2020, dropping Mays to sixth on the all-time list.

Always averse to controversy, Mays professed to have no opinion about ballplayers who used performance-enhancing drugs. “I don’t even know what that stuff is,” he said. On April 12, 2004, when Bonds, under a cloud of suspicion, launched his 660th home run, his 72-year-old godfather walked on the field to embrace him.

‘The Catch’

Mays’s most famous defensive play lives in lore as “The Catch,” against the Cleveland Indians in the 1954 World Series opener.

It was an over-the-shoulder grab of a smash by Vic Wertz late in a 2-2 game, with two Cleveland runners on base. Mays sprinted deep into the valley of center field at the Polo Grounds, his back to the infield, and somehow tracked the ball as it rocketed above and directly behind him. He caught it in full stride just shy of the wall, about 450 feet from home plate.

Because of the Polo Grounds’ uniquely vast center field, it was not unheard of for a runner to tag up and score from second base on a flyout as far as Wertz’s. The Say Hey Kid had done it several times himself. However, with runners on first and second and one out after The Catch, Mays delivered the ball to the infield in a flash, whirling and falling to his knees (and losing his cap) as he unleashed “the throw of a howitzer made human,” one observer wrote. It preserved the tie.

DiMaggio, who had retired three years earlier, witnessed the play from the press box. According to Hirsch, “Joltin’ Joe” marveled at Mays’s courage, barreling so close to the concrete wall, halting only when the ball landed in his glove. But Mays, as intelligent a player as he was physically gifted, said he wasn’t worried about a crash in his gallop toward the warning track. He was thinking further ahead.

“Soon as it got hit, I knew I’d catch this ball,” he explained. “... The problem was [Cleveland’s] Larry Doby on second base. … Suppose I stop and turn and throw. I will get nothing on the ball. No momentum going into my throw,” and Doby might have scored, giving his team the lead. “To keep my momentum, to get it working for me, I have to turn very hard and short and throw the ball from exactly the point that I caught it.”

Sports scribes would write that Mays made the lightning throw instinctively, a term that irked him. “All the while I’m runnin’ back, I’m planning how to get off that throw,” he told Hirsch. “The momentum goes into my turn and up through my legs and into my throw.”

Doby stopped at third base and, three batters later, the top of the eighth inning ended with the game still knotted. In the 10th, Mays walked, stole second and scored on a home run, and the underdog Giants went on to sweep the Series.

For Mays, it was the second of four trips to the Fall Classic and his only championship. He won his only batting title in that 1954 season, with a .345 average, and the first of his two National League Most Valuable Player awards. The World Series MVP trophy, named after Mays since 2017, is a bronze rendering of The Catch.

At the end of 1957, the Giants moved to San Francisco, where DiMaggio, a revered Bay Area native, had been a minor league star before ascending to the Yankees. To local fans, “There was no other center fielder except Joe,” Mays said in a memoir, recalling the wary reception he got at his new home ballpark. In time, Mays came to be idolized by San Franciscans, who viewed him, into his elder years, as a civic treasure. But initially he encountered blatant racism.

He was openly rebuffed when he tried to buy a house in a white neighborhood. Later, in 1959, a hate message in a Coke bottle shattered one of his windows. He bore such indignities quietly and was reluctant all of his life to speak out about bigotry, believing that racial progress was best achieved through stoic self-improvement, according to Hirsch’s authorized biography.

His hero Jackie Robinson, a civil rights activist, ridiculed Mays’s genial public image in a 1964 memoir, criticizing him harshly for not lending his voice and celebrity to the struggle for racial justice.

“Different people do things in different ways,” Mays responded in the press. “I can’t, for instance, go out and picket. I can’t stand on a soapbox and preach. It isn’t my nature.” He said he was aiding the cause of equality by counseling young players and modeling hard work and a clean lifestyle as key to success.

Meanwhile, playing in the devilish bay winds of San Francisco’s since-demolished Candlestick Park, Mays continued to post big hitting numbers, win Gold Gloves and run the bases with artful daring. Watching Mays race around second base reminded writer Roger Angell of “a marvelous skier in midturn down some steep pitch of fast powder.”

He led the Giants to the 1962 World Series with 49 home runs and 141 runs batted in. In 1965, he hit .317 with 52 homers to earn another MVP Award, 11 years after his first. In the intervening 10 seasons, he had been in the top six in National League MVP voting nine times.

For all his wondrous deeds, though, there’s an enduring memory of Mays as an aged athlete who hung on too long.

In May 1972, he was among baseball’s highest-paid players, making $165,000 a year in San Francisco, yet his skills were fast eroding. Acquired by the New York Mets in a trade that month, partly for his sentimental box office value, he finished as a struggling backup outfielder in the city of his youthful glory.

In the 1973 World Series, after entering Game 2 in Oakland as a ninth-inning pinch runner, Mays, 42, tripped and fell while rounding second base. That stumble proved harmless. But in the bottom of the inning, fighting a bright sky in center field and hampered by a knee brace, he botched a catchable fly ball in a costly miscue, belly-flopping to the turf in the final defensive appearance of his career.

Mays, whose flub opened the door to the Mets’ blowing a 6-4 lead, wasn’t the only fielder blinded by the sun that day — just the best remembered. It’s often forgotten that his redemptive two-out single in the 12th inning drove in the Mets’ go-ahead run as New York took Game 2 from the eventual champion Oakland A’s. In the Series’ remaining five games, after which he retired, Mays left the bench once, to pinch hit, and grounded into a force out.

“I just felt baseball was a beautiful game,” he said years later, adding, “I just wanted to play it forever, you know?”

A baseball prodigy

Born May 6, 1931, in Westfield, Ala., near Birmingham, Willie Howard Mays Jr. was the son of a 16-year-old schoolgirl track star and a young mill worker dubbed “Cat” for his quickness as a semipro ballplayer.

Growing up, Mays was a baseball prodigy, good enough at 17 to break in professionally with the 1948 Birmingham Black Barons in one of the storied Negro Leagues, long the highest level of the segregated sport open to Black players. He wasn’t allowed on road trips with the men until school let out for the summer.

The majors had begun integrating in 1947, and in 1950, the Giants gave Mays a $4,000 bonus for signing a $250-a-month contract (the Black Barons owner got $10,000 for parting with him). More than a month into the 1951 season, through 149 at-bats, he was hitting an otherworldly .477, with power, for the Giants’ top farm club and was called up to New York.

After being voted National League rookie of the year, Mays was drafted into the Army and missed most of the next two seasons, playing on a military team in Newport News, Va., during the Korean War. He later said, “I probably would have hit 40 [home runs] each year” for the Giants, and possibly broken Ruth’s long-standing record of 714 before Hank Aaron did in 1974.

Mays came back in 1954, the year of The Catch, belting 41 homers to go with his batting crown as the Giants rose from fifth place without him the previous season to World Series champs.

In the early 1980s, well after their playing days, Mays and Mantle were barred from any involvement with major league teams because they were being paid by casinos to schmooze with patrons. The bans were lifted in 1985, and Mays joined the Giants as an adviser, eventually with a lifetime contract. In 2015, President Barack Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

Baseball great Willie Mays smiles prior to a game between the New York Mets and the San Francisco Giants in San Francisco, Aug. 19, 2016. Mays, the electrifying “Say Hey Kid” whose singular combination of talent, drive and exuberance made him one of baseball’s greatest and most beloved players, has died. He was 93. Mays' family and the San Francisco Giants jointly announced Tuesday night, June 18, 2024, he had “passed away peacefully” Tuesday afternoon surrounded by loved ones. (Ben Margot/AP)

Mays’s marriage to the former Marghuerite Wendell ended in divorce in 1963. Eight years later, he married Mary Louise “Mae” Allen, who died in 2013. Survivors include a son, Michael Mays, from his first marriage.

He also is survived by Barry Bonds, whose father, Bobby Bonds, was a Giants rookie in 1968, the year Barry turned 4. Mays befriended the elder Bonds and became godfather to the future home run king.

Despite the sport’s many intricacies and all the work he put in, physically and mentally, to master them, Mays sometimes described his virtuosity on the field in elemental ways.

“It’s a very simple game, baseball,” he told interviewer Charlie Rose in 2010. “When they hit it, I catch it. When they throw it, I hit it. Very simple.”