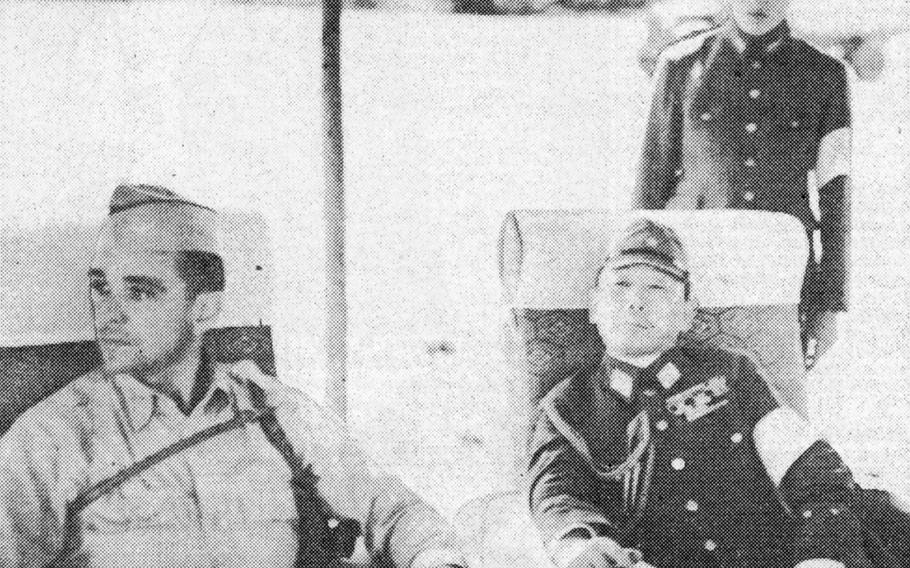

Col. C. H. Tench, left, of General Headquarters for the Supreme Allied Command, confers with Lt. Gen. Seizo Arisuyu after the landing at Atsugi airfield near Tokyo by Americ an Army and Navy representatives. (U.S. Navy)

It seemingly came out of nowhere.

The Dec. 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor by a Japanese carrier force knocked eight U.S. battleships out of commission, destroyed almost 200 aircraft and left about 2,400 Americans dead.

With the U.S. fleet crippled, Japanese forces struck Guam, Wake, the Philippines, Hong Kong and Malaya, quickly executing plans to roll across throughout Southeast Asia and the South Pacific in an attempt to create a defendable zone against expected U.S. retaliation.

A day after Pearl Harbor, the U.S. declared war on Japan, starting a nearly four-year campaign in places most Americans had never heard of. The conflict would end in stunning fashion, with the only two atomic bombs ever used in war.

In the early months of the conflict, the outlook for the Allies looked bleak.

On April 9, 1942, about 15,000 American and 60,000 Filipinos surrendered on the Bataan Peninsula of the Philippines after holding out there for three months. A month later, another 11,000 U.S. and Filipino soldiers surrendered on Corregidor Island in Manila Bay — capping the biggest capitulation of U.S. military forces since the Civil War.

To the west, Japan overran Britain’s supposedly impregnable stronghold of Singapore, killing about 5,000 mostly British and Australian troops and capturing 85,000 more in what Prime Minister Winston Churchill described as the “largest capitulation” in British military history.

A bombing raid on Darwin, Australia, in February killed 243 and added to the feeling of inevitability of Japanese conquest.

Several events in 1942, however, raised Allied morale, the first by air, then two at sea.

Lt. Col. James Doolittle led a daring bombing air raid over the Japanese mainland in April, an assault that lifted the spirits of an American public still smarting from the Pearl Harbor attack.

The U.S. Navy turned back a Japanese bid to isolate Australian and New Zealand in the Battle of the Coral Sea off New Guinea, despite great cost in ships and aircraft.

To the north, the Battle of Midway proved decisive. Japan had hoped to lure the U.S. fleet into a trap and finish the job begun in Pearl Harbor six months before. But the U.S. had broken the Japanese code and knew the strike was coming.

During nearly five days of desperate combat, Japan lost four heavy aircraft carriers. The U.S. lost the carrier Yorktown and a destroyer. But the Americans were able to continue production while Japan’s capacity to rebuild its fleet flagged.

In New Guinea, the Australians turned back a Japanese ground attack on the Australian base at Milne Bay in Japan’s first land defeat of the war.

From that point on, Japan would steadily lose territory until the end of the war.

The long U.S. advance toward the Japanese mainland began with the amphibious landing by the Marines on Tulagi and Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands in August 1942. By January 1943, the Japanese evacuated Guadalcanal.

In November 1943, U.S. troops invaded Makin and Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands, followed by invasions the Solomon and Marshall islands.

Capturing Saipan, Guam and Tinian in the Marianas island chain gave the U.S. airfields to strike the Japanese mainland about 1,300 miles away. Realizing the danger from the air, Japan fought to hold Saipan like no other island battle before.

TIMELINE | From sprawling empire to crushing defeat in 40 yearsAfter landing on Saipan in June 1944, almost 3,000 Americans died and more than 10,000 were wounded in fierce battles dubbed the likes of “Hell’s Pocket,” “Purple Heart Ridge” and “Death Valley.” Nearly all the 30,000 Japanese defenders died in the three-week campaign, and about 1,000 Japanese civilians committed suicide by jumping off cliffs rather than surrender.

Japan’s bid to turn back the Americans in the Marianas at sea ended in disaster in the two-day Battle of the Philippine Sea, where the Japanese lost three carriers and more than 600 aircraft. That crushed Japan’s remaining aircraft carrier force.

In October 1944, American forces invaded the Philippines, landing on Leyte Island to avenge the defeats in Bataan and Corregidor.

Japan’s bid to repel the Philippine invasion by sea ended in a decisive defeat in the four-day Battle of Leyte Gulf, the largest naval engagement of World War II. The Philippine campaign ended five months later in the climactic Battle of Manila, the bloodiest urban fighting of the Pacific War.

Two years of major losses had significantly weakened the Japanese. But they were not broken. As the Allies closed in on Japan’s home islands, Japanese resistance grew more ferocious, even as the prospect of ultimate defeat loomed larger.

Suicide pilots, known as the “kamikazes,” first struck U.S. warships in the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Japan would dispatch more than 2,000 of them before war’s end.

Ferocious fighting on the islands of Iwo Jima and Okinawa offered a foretaste of what the Americans could expect if they invaded Japan’s main islands. On Iwo Jima, a tiny 8-square-mile volcanic atoll about 660 miles south of Tokyo, about 21,000 Japanese soldiers were dug in in February 1945 with a vast network of bunkers, tunnels and hidden guns impervious to aerial bombing.

By the end of the 36-day battle, only about 1,000 Japanese soldiers remained alive. The U.S. suffered about 26,000 casualties, including 6,800 dead. The iconic photo of Marines and a Navy corpsman raising an American flag atop Mt. Suribachi became the most memorable image of the Pacific war.

The ferocity of Iwo Jima was eclipsed by 82 days of fighting on Okinawa in the Ryukyu island chain. The amphibious assault on Okinawa and nearby islands, which began in late March, was the largest of the Pacific war.

Okinawans old enough to remember the invasion still call it the “Typhoon of Steel,” as an invasion fleet of 1,500 ships pummeled the island. A landing force of 182,000 men, almost double the number that went ashore at Normandy on D-Day, met surprisingly little resistance during the first days after landing.

But the troops had walked into a trap in the south. As kamikaze pilots blitzed the ships, Japanese ground forces launched fierce attacks. In roughly the first two months of battle, seven kamikaze waves involving 1,500 planes from the mainland and modern-day Taiwan descended upon U.S. forces.

Monsoon rains transformed the landscape in a greasy mix of mud, blood and corpses as the stench of unburied American and Japanese bodies permeated the stifling tropical air.

By the time the battle ended on June 22, Okinawa had become with deadliest fight of the Pacific war, with more than 12,000 Americans dead and another 50,000 wounded. About 150,000 civilians and 77,000 Japanese soldiers had died.

With the gore and fatigue of Iwo Jima and Okinawa still hanging heavy, American military and civilian leaders looked with dread on the prospect of invading Japan’s main islands, slated for November 1945.

In Europe, Germany surrendered in early May. But the euphoria of victory in Europe was tempered by the prospect of hundreds of thousands more casualties before Japan could be subdued.

The Soviets had agreed secretly to enter the war against Japan after Germany’s defeat — a welcome development for the Allies but not enough to eliminate the prospect of more suffering and death for a war weary world.

The end of the war came as dramatically as it begun. On Aug. 6, a U.S. B-29, dubbed the “Enola Gay,” dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, destroying the city and tens of thousands of its inhabitants in a heartbeat. Three days later, a second bomb destroyed Nagasaki. The same day the Soviets entered the war and sent thousands of troops against the Japanese in Manchuria.

Less than a week later, Emperor Hirohito announced in an unprecedented radio broadcast that Japan would surrender.

Japan formally surrendered Sept. 2 aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. History’s most destructive war was over. Japan and Germany would transform into democracies and some of America’s closest allies.

But the world was now faced with a new and terrifying weapon that would transform the very nature of war.

Stars and Stripes researchers Norio Muroi and Catharine Giordano contributed to this report.