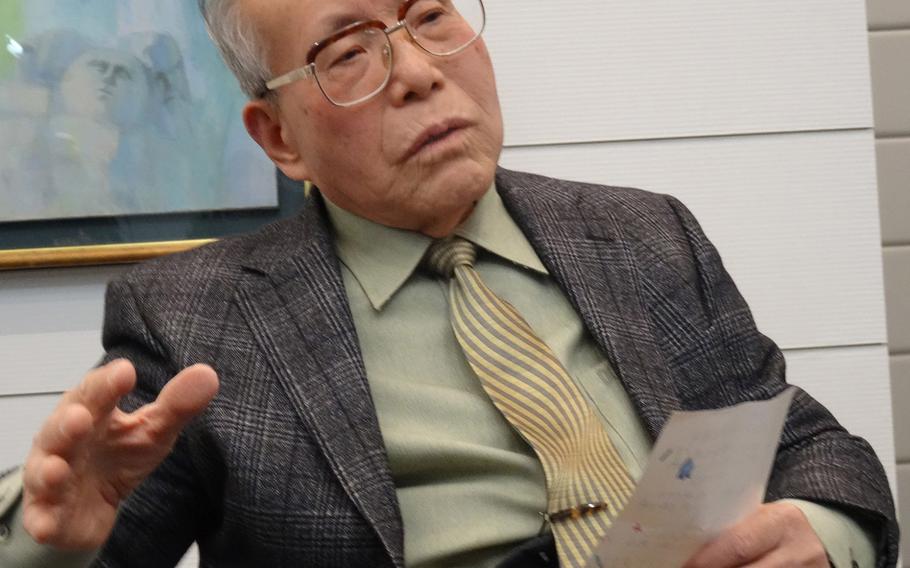

Shigeaki Mori, 77, a Hiroshima historian, recounts the aftermath of the 1945 Atomic bombing in Hiroshima to Susan Archinski, a niece of Normand Brissette, who was exposed to radiation from the bomb. (Chiyomi Sumida/Stars and Stripes)

HIROSHIMA, Japan — In the waning days of World War II, at least a dozen U.S. aviators were captured and transferred to Hiroshima after their planes were shot down while crippling the heart of Japan’s remaining naval fleet.

Their time as POWs didn’t last long. Less than two weeks after they were taken to the Chugoku Military Police Headquarters, the first atomic bomb used in war went off a quarter mile away. Most of the Americans died the same day; radiation sickness claimed the rest.

News of the deaths was not initially released, and even their families didn’t know how they died for decades.

But the work of Shigeaki Mori, a local historian who was only 8 at the time of the blast and survived by a stroke of luck, pieced together what happened, spending years digging through mountains of official documents, listening to numerous interviews with witnesses and comrades of the fallen Americans, and tracking down their families.

Finally, he was about to meet one of the relatives.

'It was shocking to me' By July 1945, Japan was on its heels. It had lost its gains in the Pacific, and Okinawa had just fallen in the bloodiest battle of World War II in the Pacific theater. U.S. bombers were pounding dozens of Japanese cities, causing up to a half-million fatalities.

Now the U.S. was facing a possible ground assault on the Japanese mainland that military leaders estimated would lead to the deaths of 250,000 American troops and millions of Japanese soldiers and civilians.

Instead, President Harry S. Truman decided to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima on Aug. 6 and Nagasaki three days later.

Mori went to school across the street from the Chugoku police headquarters. One week before the bombing, he was transferred, for reasons he still doesn’t know, to another school about 1.5 miles west of the epicenter. It saved his life.

He was on his way to class, walking on a bridge over a river with his friend. He heard a roaring sound and saw a horrifying flash. The next moment, the shock wave sent his body flying in the air, like a leaf blown away by wind, before landing in the water, he said. Mori later heard that everyone else on the bridge died, including his friend, who suffered severe burns. So did everyone at his old school.

Later in the evening, he saw his school auditorium filled with wounded and the schoolyard littered with heaps of corpses.

“To this day, I am amazed at how lucky I was,” he said ““I was exposed to a huge amount of radiation and I even drank water that was contaminated with radiation. Also, I was exposed to black rains.”

Mori had just become a hibakusha, a Japanese word created for survivors of the August 1945 bombings that effectively ended World War II. Japan surrendered days later.

In the early 1970s, Mori came to know the fates of the American POWs who fell victim of the A-bomb along with about 140,000 Japanese. A man who could easily have been filled with bitterness over the bombing instead devoted himself to research.

“When I first learned of the American victims, I realized that none of them had been officially recognized as a victim of the Atomic bomb. It was shocking to me,” Mori said. “Unless someone speaks for them, their sacrifices would be thrown into darkness. I wanted to shed light on those Americans who fell the victims of the bombing just like other 140,000 people.”

By 2009, he had officially registered the POWs’ names and photographs at the national memorial in Hiroshima as a way to pay respect for their sacrifices. He also erected a private memorial plaque near the epicenter to console the souls of the Americans.

But he always thought something was missing.

“I’ve always wished to have someone from their families to come here and offer a prayer for them. Today my dream came true,” Mori said as Susan Archinski stood by his side in a park near Hiroshima Castle in March.

Archinski, 55, of Massachusetts, is a niece of Normand Brissette, a 19-year-old Navy combat gunner from Lowell, Mass., who served the SB2C Helldiver. It was among 40 planes that took off from the USS Ticonderoga on July 27 on a mission to attack the imperial Japanese navy heavy cruiser Tone anchored in Kure, about 21 miles west of central Hiroshima.

Piloted by Raymond L. Porter, the plane was about to return to the aircraft carrier when it was hit by anti-aircraft fire from the Tone. Both Brissette and Porter safely parachuted out and were able to get aboard a life raft dropped from a fellow fighter plane behind them.

Before a U.S. rescue team could arrive, however, they were captured by Japanese imperial soldiers patrolling nearby waters on a motor boat. They were taken to Chugoku later that day.

Visiting the site While in a wheelchair pushed by his wife Kayoko, who also survived the bombing at age 2, Mori took Archinski to the sites where her uncle had gone after initially surviving the nuclear blast — to the moat of Hiroshima Castle, where Brissette and his comrade, Neal, were found, to an army hospital (now used as an automobile company’s warehouse), where both succumbed to radiation poisoning on Aug. 19, and to a grave site where they were cremated and buried.

“It is very touching that I am walking the same soil that my uncle did,” Archinski said, standing by the moat.

She said she learned of her uncle’s death in 1975, but never knew the details. Her father, Raymond, was 15 when his older brother volunteered to join the Navy. Every time her father started to talk about his brother, he choked up, she said.

“To this day, he has a hard way of dealing with it,” she said.

She said her father told of one day wearing a pair of pants that his brother left behind.

“My father found a one-dollar bill in the pocket, so he mailed it to his brother,” she said.

Then Normand sent it back to him, telling him that he could keep it.

“That’s when my father starts crying and is never able to finish the story,” she said.

'There is no 'us or them'' Archinski had another mission on this tour. It was for a documentary film of her late uncle and his 11 fallen comrades. Called “Paper Lanterns,” it is expected to be released in November.

Accompanying her on the tour to Hiroshima was the film’s director, Barry Frechette, 44, of Massachusetts.

In 2012, Frechette learned of the fate of Brissette through a book compiled by Archinski’s husband, Tony. It was meant to relate the history of Normand among his family and close friends, but Frechette felt the story should have a wider audience.

“I was really captured by what he must have gone through,” Frechette said.

He said he tried to put himself in Brissette’s shoes, but it was impossible to imagine.

Frechette then realized that the story of the lost POWs was little known in the United States. Further motivation came from a 2012 Stars and Stripes story on Mori.

“I felt …someone had to take some action to get Mr. Mori’s actions out to the public here in the states,” he said. “I would also find a way to speak of the sacrifice of Normand, who suffered just like all the Japanese.”

He later found that his great-uncle was Brissette’s best childhood friend, who also still seeks closure for the loss.

Mori looks forward to seeing the film because it will tell the stories of those who suffered and died quietly, thousands of miles away from home.

“My only wish is to give them light that they well deserve,” he said, adding that the peace we enjoy today stands on the sacrifices made by those who died in the war, he said.

“This must be known by many and made sure to pass down to future generations.”

Archinsky also visited Etajima, the island where the Tone was berthed at the city of Kure.

Hiroshi Tsuda, who was 5 at the time, described how the U.S. intensive air raids shook the entire island, chopped the Tone in half and chopped off a big portion of a mountain where the heavy cruiser had been sheltered. A monument now stands one the remaining part of the mountain to commemorate 128 crewmembers and 17 residents who died in the attack.

Mori said he was deeply moved to see Archinski offering a silent prayer before the monument, her eyes filled with tears.

“She made me realize once again that there is no “us or them” in the tragedy of war,” Mori said.