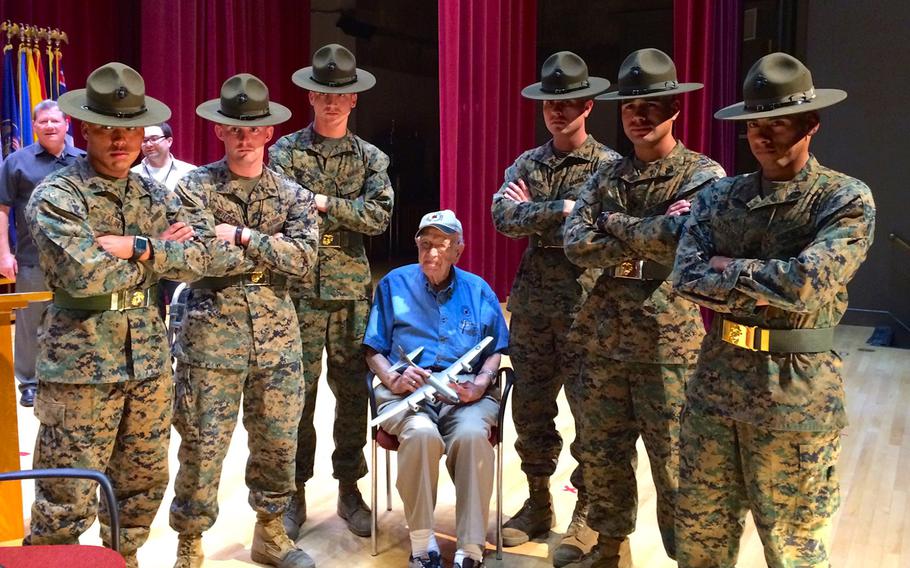

Marine drill instructors pose for a photo with Raymond ''Speedy'' Biel, who served as a B-29 co-pilot during World War II. Biel spoke to the Marines about his experiences, including participating in both missions to drop atomic bombs on Japan. Biel said the mission was so secret that he didn't know about the atomic bomb until after the first mission was over, but said the men in his unit were all happy when they heard about it, because they ''knew the war was going to end.'' (Jennifer Hlad/Stars and Stripes)

When Raymond Biel was in flight school in the early 1940s, he thought he might be a co-pilot in a fighter. Instead, he was chosen to fly the B-29 Superfortress, a new bomber for the U.S. military.

“We didn’t know what that was,” he said. “We had never heard of them.”

The planes were so new that they weren’t ready to fly yet, so the men practiced flying B-17s.

When the B-29s finally came in, Biel’s pilot gave him a manual to read, which was “about the size of a phone book,” he said. He read it cover to cover and returned it about two days later, earning his call sign, “Speedy.”

Not long afterward, a colonel told then-2nd Lt. Biel that he was going to be in a top secret program, and he wasn’t allowed to talk about it to anyone.

Biel and the rest of the new unit, the 509th Composite Group, were moved to Utah for training, where they practiced dropping bombs in the desert.

Then they shipped out to Tinian, which at the time housed the busiest airport in the world. It was also close enough to Japan to fly round trip without refueling.

On Aug. 6, 1945, after several training missions dropping conventional bombs on Japanese islands, Biel’s plane, the “Full House,” along with six other bombers, flew to Japan for their secret mission.

The plane was tasked with checking the weather over Nagasaki, while other planes flew over Hiroshima and Kokura.

It wasn’t until Biel landed back at Tinian that he learned the true purpose of the mission: to deliver the first atomic bomb.

“We had no idea,” Biel said. “That was the most secret program the Air Force ever had.”

Col. Paul Tibbets, who flew the plane that dropped that first bomb, was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross as soon as he got out of his plane, and Biel said the airmen had a “beer bash” that night to celebrate.

Three days later, Biel’s plane flew to Iwo Jima to wait, as five other planes flew to the mainland for weather reconnaissance and the second bombing.

But it was cloudy at their primary target, Kokura.

The B-29 carrying the second atomic bomb flew around for about an hour before heading to Nagasaki, but clouds threatened to hamper efforts there as well.

The crew was less than a minute from dropping the bomb by radar, when suddenly, there was a break in the clouds, Biel said. The plane dropped the bomb through the hole in the clouds. It missed its intended target by three miles.

The men would later learn that there was a prisoner of war camp in the intended strike zone: about 12,000 British prisoners were saved by cloud cover.

Biel, now 92 and living near Long Beach, Calif., said that while some may ask whether dropping the bomb was the right decision, he and his fellow airmen did not question their orders.

“When we found out that they were going to drop the second bomb, we knew the war was going to end,” he said. “We were all happy.”

Now, Biel travels around southern California with his friend, retired Navy Capt. Richard Suttie, speaking to groups about his experience; he told his story to Marines at Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego earlier this year.

Suttie told the Marines the U.S. was already planning an invasion of mainland Japan, but since there were only a few places where that number of troops could land, the Japanese army was well aware of where American troops would be coming ashore. Casualties were expected to be around 80 percent, he said.

And the Japanese would rather commit suicide than be taken prisoner, Biel said, which would have made the looming battle even more deadly.

Since Suttie has been traveling with Biel, he said, several people have come up to him to say their fathers would likely have been killed in that invasion if the bombing had not moved Japan to surrender. Some ships were already on their way across the Pacific, he said.

The Japanese had sworn to fight to the last man, said Col. Mark Tull, commander of Headquarters and Service Battalion at the recruit depot.

“Rest assured, those weapons saved lives, and frankly, saved the world,” Tull said.

Biel said he and the other members of the crew received air medals for their part in history, though he’s not sure what happened to the photographer who was sent to take pictures of the first explosion but forgot to remove the camera’s lens cap.

And then, less than four months after dropping the bombs, Biel was back in the United States. He was discharged from the Army Air Corps the day after Christmas.

He went on to attend dental school at the University of Southern California – in part because the mother of the girl he had been chasing since high school told him her daughters would only marry college graduates.

He graduated in 1956, and three days later, he said, “I married that gal.”

hlad.jennifer@stripes.com Twitter: @jhlad