()

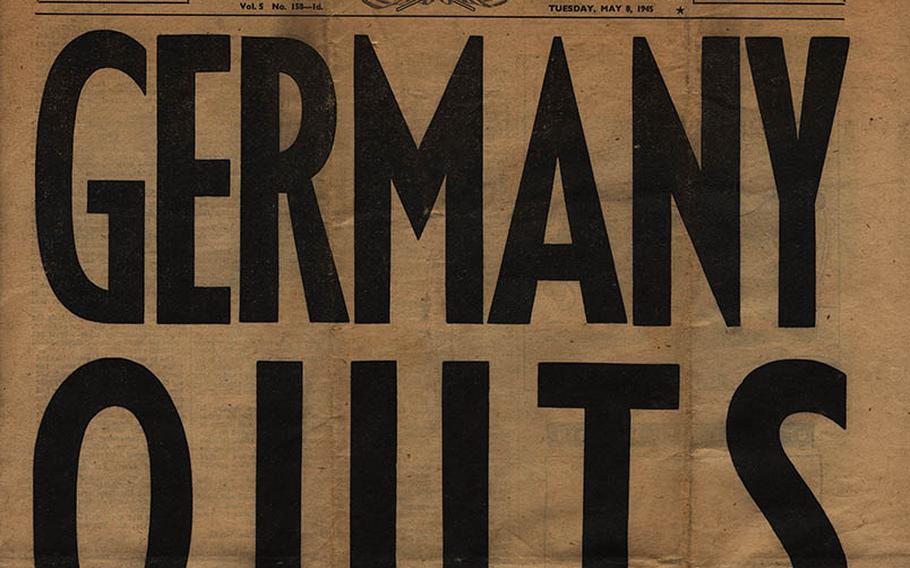

When did World War II end officially in Europe? It depends on whom you ask.

A series of German military surrenders throughout the Continent, culminating in two “official” capitulations two days apart, resulted in “Victory in Europe Day” being celebrated May 8 in the U.S. and Western countries, and May 9 in Russia and some former countries of the Soviet Union.

This year — which marks the 70th anniversary of the Allied victory in World War II — the difference is noteworthy because Western leaders will be boycotting the Moscow celebrations including the annual military parade on Red Square in protest over Russia’s actions in Ukraine.

Most European nations consider May 8 as the day when the Germans signed an unconditional surrender document in Reims, France. But Russia and several other nations celebrate May 9, the date when the “instruments of surrender” were signed in Berlin.

The collapse of the three principle Axis members — Germany, Japan and Italy — began on April 27, 1945, when Italian partisans captured fascist dictator Benito Mussolini and his mistress and executed them, hanging their bodies upside down at a gas station in Milan. Two days later, German officers arrived at the headquarters of the British army near Naples and surrendered Nazi forces in Italy, handing over nearly 1 million prisoners of war to the Allies.

On April 30, Adolf Hitler committed suicide in his fortified bunker deep below his bombed-out offices in Berlin, and two days later the German military surrendered the capital to the advancing Soviet army.

After Hitler’s death, his designated successor, navy commander Adm. Karl Doenitz, assumed power as head of an administration known as the Flensburg Government in northern Germany, which initiated the overall German surrender.

Doenitz sent a representative, Adm. Hans-Georg von Friedeburg to the headquarters of British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery near Hamburg with instructions to surrender all German forces in northern Germany, the Netherlands and Denmark. After two days of negotiations, the two sides signed the articles of surrender on May 4.

On May 6, Doenitz sent his army commander, Gen. Alfred Jodl and von Friedeburg to Gen. Dwight Eisenhower’s supreme Allied headquarters in Reims, France, to negotiate the surrender of all the German forces. Instead, the German officers were received by Eisenhower’s chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Walter Bedell Smith, who refused to negotiate and demanded an unconditional surrender.

“The German aim … was to stall for a few days in order to have time to move as many German troops and refugees as possible from the path of the Russians so that they could surrender to the Western Allies,” historian William L. Shirer wrote in “The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich,” his seminal study of Hitler’s empire.

“But it was in vain. Eisenhower saw through the game,” Shirer wrote. Eisenhower instructed Smith to inform the Germans that “unless they cease all pretenses and delays” he would close the entire Allied front to prevent any more Germans from fleeing the Soviets.

Jodl and von Friedeburg consulted with Doenitz, who realized he had no choice and told them to accept Eisenhower’s demand. They returned to Reims on May 7 and signed the surrender documents effective at 23:01 hours the following day, May 8.

But Soviet leader Joseph Stalin insisted that the surrender be confirmed in Berlin, the heart of Hitler’s empire. Since the Soviets had done most of the fighting and had suffered the overwhelming majority of Allied casualties, Stalin wanted Marshal Georgy Zhukov, as the representative of the Soviet Supreme Command, to accept the surrender, rather than the Soviet liaison officer at Eisenhower’s headquarters.

The other Allies agreed. They wanted the top German field marshal sign rather than a subordinate general, in part to avoid a repetition of the end of World War I, when a German civilian opposed to the war signed the armistice rather than the senior military commander. That led to allegations that the German army had been “stabbed in the back” by feckless politicians, an accusation repeated by Adolf Hitler during his rise to power.

A multinational delegation from Eisenhower’s headquarters, including U.S. Gen. Carl Spaatz, flew to Berlin on May 8 to sign the final document along with Zhukov and the supreme commander of all German forces, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel.

The ceremony took place at the headquarters of the Soviet military administration in Berlin’s Karlshorst district. The organizers expected to sign the formal act of surrender in the early afternoon. But because of Keitel’s unsuccessful attempts to insert some minor changes in the language and variances in the Russian translation of the text, the actual signing had be postponed until just after midnight on May 9.

Moscow time was two hours ahead of Berlin, and celebrations broke out as soon as word of the surrender was received. Since then, the Russians have marked May 9 as Victory Day.

Among the signers, von Friedeburg committed suicide a few days later out of shame for the defeat, while both Jodl and Keitel were hanged in 1946 as war criminals.

Despite the double surrender, German troops continued to resist in some areas, including Prague where Czech insurgents and Nazi SS troops fought on until May 11. The war’s last battle on European soil was fought between Yugoslav partisans and retreating Nazis on May 15, 1945.

In 1990, the Soviet Union and Germany decided to establish a museum at the site of the historic signing event in Karlshorst. It was opened in 1995, on the 50th anniversary of the surrender ceremony, and includes documents, posters, photographs, armaments, uniforms and flags associated with the war’s final act.