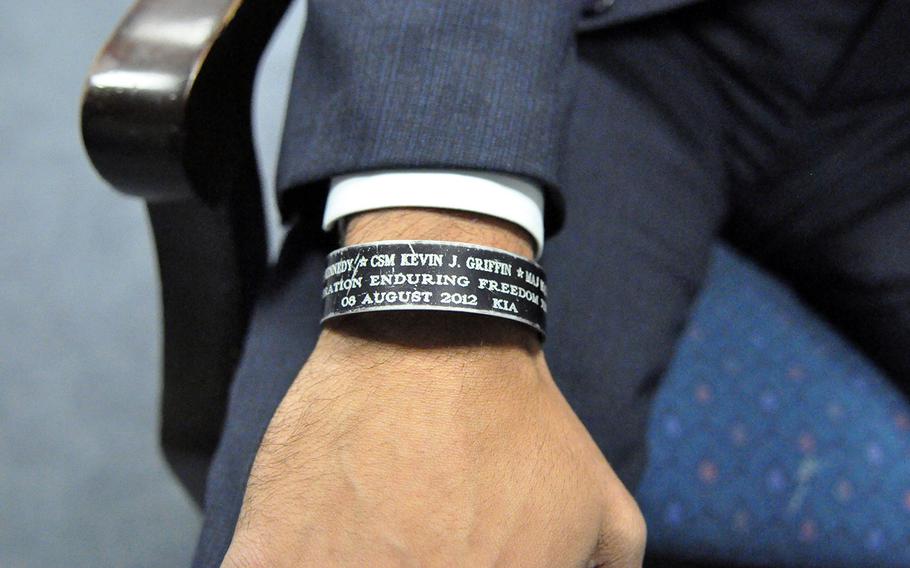

Capt. Florent Groberg displays his wristband that commemorates servicemen who were killed by an Afghan suicide bomber. They include Command Sgt. Maj. Kevin Griffin, of the 4th BCT, Air Force Maj. Walter David Gray, Army Maj. Thomas Kennedy and Ragaei Abdelfattah, a USAID foreign-service officer. (Ken-Yon Hardy/Stars and Stripes)

WASHINGTON — Army Capt. Florent Groberg left Afghanistan in 2012 with a mangled left leg that required more than 30 surgeries and confined him to a hospital bed for three months. It was the most difficult time of his life.

“All you can do is sit there with your own thoughts for hours and hours and hours and hours,” he told Stars and Stripes on Monday. “You don’t sleep, you’re on drugs for the pain and things like that.

“All I could think was just, ‘How?’”

In Afghanistan, Groberg was charged with protecting a formation of senior leaders on Aug. 8, 2012. When an insurgent armed with a suicide vest attacked the group, Groberg tackled him, and the vest exploded. The Army said his actions that day saved many lives.

For his heroics, Groberg will receive the Medal of Honor on Nov. 12 from President Barack Obama.

But receiving the military’s highest honor for battlefield valor was far from Groberg’s mind during his early days at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md. He spent much of the time grappling with questions about his future: Could he stay in the Army? Would he ever run again? Why did he survive?

“What is the positive?” the 32-year-old would ask himself.

During the tedious hours of recovery, Groberg discovered the answer: He was alive. And he realized he could dedicate his life to honor the four people who did not survive the attack in Abadabad: Army Command Sgt. Maj. Kevin Griffin, Air Force Maj. Walter David Gray, Army Maj. Thomas Kennedy and Ragaei Abdelfattah, a USAID foreign-service officer.

“There was no reason for me to try to piece it back together,” Groberg said Monday. “For one, I’ll never have the answer — it just happened. So what do I do now? I live my life to the best of my ability for four individuals, who unfortunately did not have the same luck — if you want to call it luck.

“Now I have a big responsibility.”

‘Incredible individuals’ On Nov. 12, Groberg, now medically retired from the Army and working as a Defense Department civilian, will stand at attention as Obama places the Medal of Honor around his neck. He will spend the entire ceremony thinking of those men who perished in that 2012 attack.

“Four incredible individuals, who I’ll never forget,” Groberg said, tapping the bracelet on his right wrist inscribed with each of their names. “I live with them right here. … I want to make sure that everyone understands that they are the true heroes in all of this.

“Those four men who we lost represent the very best of us, and I just hope to be able to honor them and be the right courier.”

He was closest to Griffin, the senior enlisted leader for his brigade — Fort Carson, Colo.’s 4th Infantry Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division — who served as a mentor to Groberg.

Groberg recalled spending time in Griffin’s stateside office, where he’d ask the senior noncommissioned officer for advice, personal and professional.

“He always was there to give me a reason behind his thinking process,” Groberg said. “He wasn’t just … ‘Hey, you need to do this,’ he was … ‘Hey, I recommend you do this, this certain way. Here’s why. This is how you’ll find success. You’re such a young officer, and this will propel you to this place.’ ”

In the years since the attack, Groberg has become close with Griffin’s family and with family members of the other two American servicemembers who died in the attack.

“This medal honestly, truly belongs to them,” he said of their families. “And on Nov. 12, I will give them all a hug and a handshake and let them know that this is for them.”

Regaining strength A lifelong athlete, Groberg lettered in varsity track and cross country at the University of Maryland and remained committed to elite conditioning through his Army career.

A 10-mile run, even while deployed to Afghanistan, was fun and also a way to clear his mind.

The sudden loss of the ability to run — Groberg suffered more than 45 percent loss of his left calf muscle and significant nerve damage, along with a blown eardrum and a mild traumatic brain injury — was frustrating. But he knew he had to remain active in order to live up to his promise to live in honor of Griffin, Gray, Kennedy and Abdelfattah.

“You have to maintain, just because of that injury you can’t … eat bad food and just sit around on the couch because I can’t run,” Groberg said. “There’s a lot of things I can do.”

He’s taken up rowing, CrossFit and hiking, proving to himself that his love of athletics and participating in sports did not have to end in the hospital.

“It’s about discipline; it’s a way of life,” Groberg said. “It’s something that I need to deal with stress, anxiety … and because of the incredible care I received at Walter Reed and support system that I had, and just the fact that in the military, you learn how to deal with adversity. I just took my training and what I believe in and just kind of ran with it.”

‘Unbelievable’ support After Groberg was evacuated from Afghanistan to Walter Reed, via Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany, he was immediately thrust into a massive support system.

His first day at the hospital he found himself surrounded by nine people in his small room in the facility about five miles from Walter Johnson High School, where he graduated in 2001.

“I’m not going to say that was a good thing, because I was still kind of out of it … and my anxiety really just kicked in,” Groberg said.

But it was an early sign of the support that he would receive in his long recovery effort. He was in Walter Reed from August 2012 through May 2015. He was medically retired in July 2015.

His parents, Gary and Klara Groberg, spent weeks by his side. Friends from high school and college visited. Any time he was having a bad day, he said, there was someone there to cheer him up.

Often that was one of the other wounded servicemembers at the hospital, many of them suffering injuries much worse than his own.

His interactions with other troops injured in combat were humbling, Groberg said. He watched guys who had lost legs and arms, and others who had been blinded. He noticed something they had in common: positive attitudes.

“They’re all smiling and they’re joking around,” Groberg said. “That’s why we are the best in the world. There’s no doubt. We have the best individuals. Americans are the best. We step up.”

He credited his doctors and nurses at Walter Reed with saving his leg, combatting several infections and other setbacks, and returning him to strength.

“I owe a lot of people,” said Groberg, a native Frenchman who moved to the United States at age 11 and became a naturalized citizen at 18. “What an unbelievable support system. I’ve been very, very lucky.”

Even with his extensive recovery, his choice to renounce his French citizenship and eventually join the U.S. military in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks on New York and Washington was “the best decision I ever made.”

The only thing he would change, he said, would to bring back the four men who died in the suicide bombing.

“If it was even possible is to take this Medal (of Honor) and give it back and say, ‘Please bring my four guys back,’ ” he would, Groberg said. “That’s way more important to me than anything.”

dickstein.corey@stripes.com Twitter: @CDicksteinDC